Larissa Khusid

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Family background

Growing up

During the War

After the War

My name is Larissa Khusid. I was born in Odessa, to the family of Iona and Maria Khusid on May 15, 1924. My father, Iona Khusid, was born on August 5, 1892 in the town of Stepantsy, in the district of Kanev, in the province of Kiev. My father was a very shy and reserved man. He didn't like to talk about himself or his family, and therefore, I can't give you an accurate picture of his life. After my father died, his neighbor, Abram Linkevich from Stepantsy, who knew my grandfather and his family, came over to our house and told me much more about my father's family than my father had.

My grandfather, Nahman Khusid, who was born in Stepantsy around 1850, was a local rabbi. People often turned to my grandfather to resolve their everyday problems. However, when they had more serious problems, they took them to the rabbi of a neighboring town. My grandfather didn't charge them for his advice, and people were convinced that his connection to God, without money, was a doubtful matter. But they loved my grandfather very much. He was a very kind and cheerful man. His family consisted of himself, my grandmother - regretfully, I don't remember her name - and seven children. They led a poor and miserable life. They lived in a small wooden house, and very often their children could only take turns going out because they had only one pair of shoes for the boys and one for the girls. In his everyday life my grandfather could make do with very little. The only things he couldn't refuse himself were his rare trips to the opera's opening night performances. My grandfather was crazy about music. He even took opera trips on Saturdays, which should have been absolutely out of the question for a religious Jew, or a rabbi. That is why I think he must have led a more secular life than he should have, according to his position. I was told that my grandfather was very close to Sholem-Aleihem, and often met with him in Kiev. My grandfather Nahman was killed during a pogrom in Stepantsy in 1919. I don't know any details of this terrible event. My father couldn't talk about it. My grandmother died in the mid-1930s. I never saw or met her.

At the end of the last century, Stepantsy was a small Jewish town with a population 80% Jewish and the rest Ukrainian. These two groups got along very well and supported each other. There was a synagogue and a church in the central square. There were hardly any jobs to be had in Stepantsy. Women were mainly housewives, and men engaged themselves in handicrafts, as tinsmiths, shoemakers, carpenters, etc. They worked hard to support their families, but what they could earn was never enough. Their families were large, and early in life, older sons began to work to help their fathers make ends meet. Parents couldn't begin to dream about giving their children an education. They just couldn't afford it. Life in Stepantsy was poor and monotonous, as it was in many other similar little towns.

Father's oldest brother, Iosif, was born in 1880. I don't know what he did for a living before the Revolution, but afterwards he lived in Leningrad. He had a wife named Eva and two sons, Alexandr and Naum. He sent them to the evacuation in Barnaul during the Great Patriotic War, while he himself stayed behind in Leningrad. He loved the arts, and worked as an administrator in one of the theaters. He loved music and the ballet, but most of all he loved ballerinas. Many of them were his lovers. My father often met with Uncle Iosif when he went to Moscow. Iosif visited Kiev only once, in 1953. Iosif died in mid-1980. His son Shurik lives in St. Petersburg.

The next sibling in my father's family was his brother Idel, born, in 1885. Idel took a degree in economics. He lived and worked in Odessa. In the early 1930s he divorced his wife, leaving her and their son Alexandr in Odessa, and moved to Kiev. He lived there with his common-law wife, Valentina Ottovna, a German - they did not arrange a lawful marriage. When the war began, Valentina convinced Idel that the Germans were a civilized people and would therefore do no harm to the Jews, and so it did not make any sense to leave home. According to what one of our distant relatives told us, Valentina Ottovna handed Idel over to policemen near the Golden Gate, an ancient historical monument in Kiev. Our relative, a Christian woman, said she had seen the Germans pushing Idel into the column of Jews walking to the Babi Yar. Idel was shot along with thousands of other Jews on September 29, 1941.

After Idel, the next two children born to the Khusid family were girls, Mikhlia, born in 1888, and Mirrah, born in 1890. Mikhlia's husband's name was Nahman - I can't remember his first name. Mirrah was married to Mendel Gurevich, an attorney in Kiev. Mikhlia had two daughters, Sarrah and Polia, and Mirrah had two sons, David and Naum. David perished on the front during the Great Patriotic War. The rest of the families were in the evacuation in Tashkent, I believe. Mikhlia died in Kiev in 1960 and Mirrah died around 1965. Their children have passed away, too.

Dora was my father's younger sister, born in 1894 in Stepantsy. Around 1900, she married Isaak Galperin and lived with him in Odessa. They had no children. When the war began, Dora left Odessa with her sisters Mikhlia and Mirrah, but Isaak had to stay on. He was too late to be evacuated, and was shot by the Germans in 1941. Dora did not remarry, and lived in Leningrad after the war. In 1975 I took her to Kiev, because she couldn't live alone any longer. In 1976 Dora was involved in a car accident and became an invalid. She died on July 21, 1977. I was at her bedside.

My father's youngest brother, David, born around 1905, lived with my parents in Odessa after their marriage. My father helped David to get education. Later, David moved to Kiev, where he married a nice Russian woman named Nyura. This was the cousin of the woman who saw my father Idel on his way to Babi Yar. David was in the evacuation during the war. He died in the mid-1980s. His son Victor lives in Kiev.

Like all the other sons of my grandfather Nahman, my father received a Jewish education in a cheder, but that wasn't enough for him. He wanted to become an educated and intelligent man. He was right to think that only a good education could help him to lift himself out of the poverty of this little Jewish town. When my father turned 13, he said "goodbye" to his parents, left his father's home, and went to Kiev on foot. There, he found a temporary job and shelter in the home of a woman who sold milk. My father slept on a windowsill in the basement that served as her shop. In exchange for food and lodging, my father had to unload milk carts that arrived from the surrounding villages early in the morning, wash out milk cans, and perform other related chores. In the evenings, my father sat and studied on that same windowsill that served as his bed. Sometimes he studied so late into the night that the milk woman would tell him to switch off the lamp. By working and studying hard, my father managed to earn a degree in economics at an institution of higher learning, the name of which I unfortunately don't know.

When World War I began in 1914, my father was recruited into the tsarist army. He was a Private in the infantry and finished the war with the rank of Private First Class of Putivl Regiment 127. In September 1916 my father was severely wounded. His legs were broken, and he was sent to the hospital, remaining there until May 1917. After being released, my father was dismissed from the army as an invalid. During his service in the tsarist army, father was awarded two George's Crosses - the highest award that Privates could get. My father never told me what deeds of his were so rewarded.

I don't know what my father did after his release from the hospital, but I know that he was in Odessa in 1920, and worked at the Odessa province's Soviet farm A Soviet farm is a collectively owned agricultural complex with no private property. People came to work on the farm, just as they would at any industrial enterprise. There, he met there my mother's older brother, Abram Ortenberg, who introduced my father to my mother's family.

My mother, Maria Ortenberg, was born in 1898 in Kishinev, the capital of Bessarabia, which was part of the Russian Empire. Mother's father, my grandfather Iosif Ortenberg, was born around 1860. There was a legend in my grandfather's family, which my mother's brother, Abram, passed on to my husband and me as our wedding gift. He wrote in his congratulatory letter to us, that he wished he could give us something more as a wedding present, but that because he was poor, the family legend was all that he had to give. The legend says that my great-grandfather, Pinhus Ortenberg, a teacher, was the first to bring an electric bulb to Vinnitsa from Europe. This same man had a friend who lost his fortune in a card game. My great- grandfather covered his friend's card debt, thereby dragging his own family into poverty. The Tzaddik of Vinnitsa cursed my great-grandfather, saying that there would be no riches in his family, but sweetened the curse somewhat with the blessing that no one in the family would die a violent death. The Tzaddik's curse and blessing held true for over one hundred years.

My grandfather had two brothers, Lazar and Wolf Ortenberg, and a sister, Leia. My grandfather's family was very musical. Lazar was an amateur musician, and played the violin very well. He was a friend of the great Russian composer Rimsky-Korsakov, whom he had met in St. Petersburg, and with whom he corresponded by letter. Lazar had a daughter, Sarrah, who married a famous Soviet commander and hero of the Civil War, a Jew by the name of Iona Yakir. Yakir was arrested on June 11, 1937. Yakir, Sarrah, their 14-year-old son Pyotr (nicknamed Petia), and Sarrah's father, lived in Kirov Street in Kiev. On the day Yakir was arrested, the authorities conducted a horrible search of their apartment. They broke the walls, furniture and floors looking for weapons and documents with which to implicate Iona as having contacts with foreign intelligence agencies, a false accusation. Yakir's son, Petia, showed them a toy gun that Iona had once brought him from Berlin when he returned from a business trip there. The entire family were arrested and taken to Astrakhan. Lazar died on the way. Sarrah was sentenced to 10 years in prison camps, and later, ten more years. Fourteen-year-old Petia was also arrested, but released in Sverdlovsk after 5 years. All the clothing he possessed was his underwear and a tyubeteika cap in which he kept his discharge papers. Luckily, on that very same day, he met some acquaintances who were in Sverdlovsk during the evacuation. They gave him some clothing, and in the evening they all went to the Musical Comedy Theater. Unfortunately, the first man Petia saw in the theater was the warden of the prison Petia had just left. Petia was immediately rearrested. This time he was charged with trying to cross the border into Iran. Petia demanded to be escorted to Beria. His request was satisfied, but when Beria began to revile Petia's father, Iona Yakir, Petia lost his temper and threw an inkpot at Beria. Petia asked to be sent to the front, but was refused. As we found out later, Stalin had decided to send Petia to the saboteurs' school. He was sent to the German rear twice, and completed his tasks successfully. Before sending him there for the third time, the authorities said to him that he would either die or come back a Hero of the Soviet Union. He fulfilled his task and returned. Afterwards, he was sent to penal exile at a gold mine. Petia was rehabilitated and returned from exile around 1955. He visited us in Kiev. I asked him once: "What would you do to Stalin if you got him?" And he replied, "Nothing. I would send him to where I was, and I would be his jailer until the end of his days." Sarrah returned from prison camp around the same time. She received a small two-room apartment in Moscow, and lived there until her death in 1977.

I have no information concerning Wolf Ortenberg, my grandfather's second brother. I believe he died long before the Revolution. His wife Leya, who resumed her maiden name Monastyrskaya after her husband's death, died in Odessa after the evacuation. She had four children. One of them, Pyotr Monastyrskiy, lives in the town of Kuibyshev, now known as Samara. He is a producer and is a People's Artist of the Soviet Union.

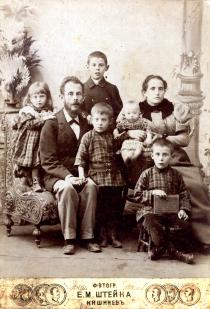

My grandfather Iosif Ortenberg, born in 1860, was also very fond of music. I don't know how he met my grandmother, but they married in Kishinev in 1880. Around 1905, their family moved to Odessa. My grandfather was a teacher. His students took classes at his home. My grandfather provided all his children with a good education. His daughters finished grammar school and his sons received further education. My grandfather was a man of advanced ideas for his time. He gave all his children a very good modern upbringing. Their family wasn't religious. Like her husband, my grandmother, Dora (maiden name - Korduner), was a woman of the world. She even smoked long, thin cigarettes. However, my mother told me that my grandmother never smoked on Saturdays. This was probably her tribute to the Jewish traditions. My grandfather rarely visited the synagogue, but he used to say that such visits helped him to keep the family together. Although the family wasn't religious, they celebrated the main Jewish holidays - Pesach, Purim and Hanukkah. The children were not at all religious. There were seven children in all, just as in my father's family. My grandmother Dora gave birth to a baby every two or two and a half years. Their large family rented a big apartment in the center of the city. In about 1905, Odessa was swept with a surge of pogroms. The janitor of the building where the family lived did not allow the thugs to enter their apartment, and the family stayed holed up there for several days. This janitor was a Ukrainian. He brought the family everything they needed. He adored my grandfather. After the Revolution, my grandfather began to work as Director of the Kindergarten at the House of Doctors. My cousins and I attended this same kindergarten. My grandfather worked there up until his last days. He died from a heart attack in 1934.

The oldest among the children was Abram, born around 1884. Abram finished high school in Kiev, and then was sent by my grandfather to the Netherlands to continue his studies. In 1914 Abram defended his thesis in economics there, and received a job offer. But then WWI began, My grandmother requested that all her children be at home. At that time, children obeyed their parents unconditionally, and so Abram returned to Odessa. In the early 1920s he worked on the Soviet farm there (he was a secretary of science), and introduced my father to his family. Abram married. He has two children, Naum and Larissa. Naum suffered much during the Stalinist years. During the war he was in the army, stationed in Iran as a topographer. After the war, he went to Moscow and submitted his application to the Kuibyshev Military Engineering Academy. There was a question in this application form about relatives abroad that Abram answered as "my father's brother is in Rumania," but nobody knew where Abram's younger brother was.

There also was a question in this form about any family members who had been repressed. Abram wrote that his aunt and her husband Yakir had been. As a result of these honest answers, Abram was summoned to the political department where he was advised to tear up the form he had submitted, and to mention nothing of the above in the new form that he was obliged to complete. In this way, he was able to enroll in the Academy. Abram was a very successful student. But when the period of struggle against the cosmopolitans began in 1949, Abram was again called to the political department and ordered to leave Moscow on 48 hours notice. He spent many years working in the Kalmyk steppes as a topographer. He came to Sterlitamak for three weeks every year to formulate the results of his surveys. Abram died in 1953, before his son Naum returned from exile. Later, Naum was allowed to move to Lithuania where he defended his thesis on land surveying. In the mid-1970s, Naum moved to Moscow, and in 1987 he emigrated to the USA with his family. He lives in San Francisco, and his sister Larissa lives there too.

The next son in the Ortenberg family was Grigoriy ("Grisha"), born in 1886. Grigoriy married a wealthy Jewish girl named Maria. It was a love match. In 1922, at the end of the Civil War, Uncle Grisha and his wife, along with their son Emil and Maria's four sisters, left for Bucharest via Constantinople on the last boat. Grisha took all the family's jewels and diamonds with him. In Bucharest, the girls opened a café that went broke, and the family's finances suffered. Grisha got a job as an economist at a big textile factory. His son Emil managed to graduate from a French college. During the war, the owner of the factory where Grisha worked helped Emil to avoid arrest. Emil and his father were lucky to remain safely in Bucharest until the Soviet Army liberated the country from the fascists. The owner of the factory escaped to France, leaving all his business to Grisha. When the first Soviet Consul arrived in Bucharest, Grisha gave him the key to the textile factory. Once more, the family could hardly make ends meet. In 1957, Uncle Grisha came to Odessa. We collected money for his return ticket. He died in Bucharest around 1970. After his death, Emil went to live with his mother's brother in Brussels. Emil was married to the sister of the Soviet Jewish writer Isaak Babel, who had emigrated to Brussels during the Revolution. Babel owned a big pharmaceutical company that he wished to bequeath to Emil, but Emil told him that Ortenbergs never dealt with commerce, and that it would turn to no good, anyway. From Brussels, Emil moved to Paris, where he now lives.

The next Ortenberg in the family was my mother's sister, Polina. Polina married Alexandr Kangun, a revolutionarys who came from a large Jewish family. Until recently, there was a Kangun Street in Odessa. It was named after Kangun's brothers, Monia and Lyova, who perished in Odessa during the Civil War. Polina and Alexandr adopted a girl. She was half-Greek and half-Jewish. Her name was Eraclia. During WWII Polina was evacuated. She died in Odessa in 1968.

After Polina, came Akiva. Sometime during the Soviet era, he changed his name to Nikolay. Nikolay was very tall. He served in the grenadier regiment in the tsarist army in Moscow. The members of this grenadier regiment appeared at the Bolshoi Opera as supernumeraries in the crowd scenes of operas such as "Life for the Tsar," and "Boris Godunov," and Nikolai had the opportunity to stand on the stage beside the great bass, Chaliapin. During the Soviet years, Nikolay was Chief Engineer of the port of Odessa.

The next child after Nikolay was Arnold. During the Soviet years, he was Chief Engineer of Odessa's canned food factory.

The youngest in the family was Iliozar. He was born after my mother. Iliozar was exceptionally good at music. My mother took him to Pyotr Solomonovich Stoliarskiy, a wonderful violin teacher. This man was semi-literate and spoke poor Russian, because, being Jewish, his mother tongue was Yiddish, but he was a God-gifted teacher. He was the first teacher of the renowned violinists David Oistrach, Lisa Gilels, Misha Fichtengolts, and many, many others. Iliozar studied at the Odessa Conservatory, and worked at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. He requested permission from Lunacharskiy to continue his education in Berlin, and moved toBerlin for his post-graduate studies. His teacher in Berlin was Professor Gesse. Later this teacher became a member of the Nazi party. In Germany, Iliozar changed his name to Elgar. In 1928 my grandfather and grandmother obtained a visa to visit Iliozar in Germany, but on the eve of their departure, my grandmother suffered a stroke, and died on February 28, 1928. My grandfather went to Germany in 1929 with my mother's older sister, Polina. Later, in 1933 when the Nazis came to power, a German newspaper published an article by Dr. Goebbels asking "for how long shall the blue- eyed Jew from Odessa who has the nickname Elgar charm the Third Reich with his tunes?" It was possible to publish one's denial in the newspapers at that time. Iliozar (Elgar) published a short denial saying that he had never concealed his origin or his Jewish identity, and that he was born and would die a Jew. By that time Iliozar had married Tamara Kogan, a Jewish girl, in Berlin. Her father was a companion of Lenin's who emigrated to France when Lenin died in 1924. After Iliozar and Tamara witnessed the anti- Semitic riot known as "Crystal Night," they ran away to Tamara's relatives in Paris. In Paris my uncle organized a string quartet consisting of four Russian Jews, all four of whom were mobilized into the French army even before the Nazis arrived. My Uncle Iliozar went on a tour to the USA with his string quartet. Later, he received a Legion of Honor Order from Errieau, France's Minister of Culture, for the propagation of French art in America. It never occurred to anybody that French art was popularized by four Jews from Russia. However, by then they had become French citizens. In 1939 Hitler attacked France. My uncle said that they all had to leave, but he wanted to the rest of the family, his wife's sister, Tamara, and her husband Leon to be able to leave as well. This caused some delay with the departure. When Hitler was almost in Paris my uncle closed the windows of the apartment and turned on the gas. He didn't want the Germans to catch him alive. Tamara managed to open the windows before it was too late, and they all fled to the south of France, almost penniless. In Marsailles they boarded a ship going to America. They arrived in America with one dollar in their pocket. My Uncle Iliozar was soon offered a job on American radio. He worked there for a long time, and subsequently became second violinist in the "Budapest Quartet," a group whose reputation as the best quartet in the world was undisputed. The first violinist and founder of the quartet was a Hungarian.

Before 1937, Abram corresponded with his brothers Grigoriy and Iliozar who both lived abroad. They were forced to terminate their correspondence due to repression, arrests and the "iron curtain." Around 1948-50, we heard by chance that Aron was still alive. One of Aunt Polia's neighbors brought her a copy of a magazine that had a picture of Iliozar with his Budapest quartet. However, we were only able to meet in 1969, when my Uncle Iliozar, who had changed his name to Edgar in America, visited the Soviet Union. In 1968 he sent a card to Aunt Polia telling her that he was coming to the Soviet Union with his wife. Polia, then 80 years old, ran to inform her relatives about his arrival. On the way, she was involved in a bicycle accident and died. I didn't tell my mother and Uncle Iliozar about Aunt Polia's death right away, but I had to inform Uncle Iliozar before his arrival. I shall never forget Uncle Iliozar's meeting with my mother in 1969. Uncle Iliozar liked me a lot. He didn't have children of his own. He visited Kiev many times afterward, and I went to visit him in America. After he stopped playing concerts, he became a professor at a College of Music in Philadelphia and gave Master Classes in Europe and around the USA. Iliozar died in 1996 at the age of 96, of sound mind. On his 95th birthday the year before, the mayor of Philadelphia came to greet him, and declared him a Citizen of Honor of Philadelphia, saying that he enriched this town and the entire United States with his music.

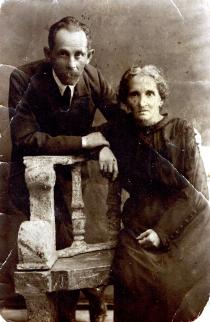

My mother was born in Kishinev in 1898. She studied at an Odessa grammar school. In 1922 she met my father and married him on June 22, 1923. They had a civil registration ceremony. Although my father grew up in the family of a rabbi, he wasn't religious, and didn't observe any Jewish traditions. He knew Yiddish, but he and my mother spoke only Russian at home. They only used words Yiddish words to emphasize or give special coloring to what they wanted to say, but I didn't understand that language. I was born in Odessa in May of 1924.

We lived in Marazli Street, then in Engels Street, in a big communal apartment with a common kitchen and primus and kerosene stoves. Aunt Tuba and her son Isaak also lived in this apartment. Tuba was a real Odessan. She spoke mixed Yiddish, Ukrainian and Russian. She taught me many Yiddish songs, like "Don't waste your time coming here, Arnchik, you won't get Zhenia, 'cause you don't deserve her, and you'll go back home a fool." Both my parents worked. My mother worked as a research assistant at Odessa's historical archives. I attended the kindergarten at the House of Doctors where my grandfather worked. From our apartment in Marazli Street, we moved to a new two-room apartment . And there I began to get acquainted with the world of music. An elderly couple lived in another apartment on our floor. Rachil Abramovna was a music teacher and David Abramovich was a mathematician. Although we didn't have a piano at home, Rachil Abramovna gave me lessons. In 1931 I went to secondary school and also to the Glazunov Music School. By this time we had obtained a piano, and music became my main hobby for the rest of my life. My music teacher Maria Lvovna Rogovaya-Filshtein, a Jew, cultivated the love of music in me. I corresponded with her for many years after. I spent a lot of my time studying music, but I was also an active young Octobrist and then a Pioneer at school.

Our family was like many other Soviet families of that time. We lived a poor but exciting life. My father worked very hard. He was Director of the paper-bleaching factory. Mama also spent a lot of time working. They had many friends of various nationalities. They got together to party on Soviet holidays and on birthdays. We always had parties at home. We had an exemplary Soviet family. We never talked about nationalities, or about our roots. I remember the disastrous year of 1933, when famine ravished Ukraine. Mama disappeared with a silver spoon or fork every now and then, and returned with food products from Torgsin. I remember Mama bringing home a big box containing lollypops. She put it in the cupboard. I was not feeling well that day and stayed at home. After Mama left for work, I ate half of these lollypops. For many years afterward I couldn't even look at the sweets.

In 1934, the Ukrainian government moved from Kharkov to Kiev. My father got a job assignment at the Polygraphy Department in Kiev. Ten apartments were constructed on Saksaganskogo Street for the management. We received a two-room apartment on the fourth floor, and lived there until the beginning of World War II.

When we moved to Kiev, my parents arranged a meeting for me with a professor from the Conservatory who told them that I should attend a special school for gifted children. I enrolled in a school in Muzeiniy Lane that was built by the order of Narkom (minister) Postyshev. Postyshev often visited our school. In 1935 he organized a New Year's party with a New Year tree. Before 1935, New Year trees were not allowed in the Soviet Union. They were thought to be a bourgeois vestige. Postyshev talked with us at this party, where there was food on the tables and waitresses in white aprons carrying ice cream. Around 1938, Postyshev was repressed and shot.

Papa became Chief of Headquarters. My father had been a member of the Communist Party since the 1920s, although he didn't become a member because of his convictions, but in order to have a career. Mama has never joined Communist Party. At that time, following Stalin's practice, many office workers worked at night, as did my father, who came home from work in the morning. Papa always walked home, even though he had a car at his disposal. He dismissed the driver in the evening. After Yakir was arrested in 1937, our family members were prepared for any turn of events. We had a small brown suitcase packed and waiting. In it We had was underwear, a razor kit and other essentials. We kept this suitcase on a chair near the entrance door of our apartment. I remember my mother walking to and from our rather big balcony, waiting for my Papa to come back from work. Strange as it was, the authorities didn't touch Papa, although he never concealed that Yakir was his relative, or that he had relatives abroad. Mama's brothers--Abram, who worked in Odessa on a Soviet farm, Nikolay, the Chief Engineer of the Port of Odessa, and Arnold, Chief Engineer of the canned food factory avoided repression and arrests as well.

Besides Yakir's family, the family of Polina Gants (maiden name - Korduner), on my grandmother Dora's side, was repressed too, at the end of the 1930s. Her husband, Iosif Gants, was Chairman of the Union of Architects of Ukraine. Polina and her husband were arrested during their vacation in Gagry. They were charged with sabotage and disappeared. Their relatives took their twins, Dolik and Dorik, to live with their families. The twins were given their names in honor of Grandma Dora. Dolik, who was a little over a year old, lived with us for a long time. I even have a picture of me with the New Year's tree in the background, and Dolik's little bed on one side. When WWII began, Dolik's grandfather, Semyon Gants, took Dolik to live with him. Polina was released after the war. Her husband, Iosif, was executed in 1938.

The situation was very different in those pre-war years. My parents looked very concerned and often talked in whispers. But we schoolchildren led a very busy life. I was very fond of music. I also studied French and German and went in for skiing. We often attended concerts at the Philharmonic and to plays. In 1939 I became a Komsomol member. It was such an important event in my life, that I remembered the number of my Komsomol membership card for the rest of my life - 8860169. I was also involved in public activities, and was Chairman of the Education Committee.

The war came as a surprise to my friends and me, although we had had training sessions and discussions of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact at school. We also saw films about fascism, such as "Professor Mumlock," but it still seemed to us that the war was somewhere far away and didn't have anything to do with us.

On June 22, 1941, my parents' wedding anniversary, I went to the Bessarabia market early in the morning to buy flowers. On the way, I was caught by the air raid alarm, which, at first, everybody thought was just another training alarm. Everyone was forced to run to the air raid shelter. Afterwards, I returned home. Nobody knew that the war had begun. Mama's brother, Nikolay, was in Kiev on a business trip, and was visiting us. When Molotov made an announcement about the war at 12 o'clock, Papa slid down to the floor very strangely, and Uncle Kolia put down his cigarette on the tablecloth. I understood then that something disastrous had happened. On this day, June 22, the opening of a new stadium with a football match was scheduled. People were walking past our house on their way to the stadium. They couldn't believe what had happened. But, of course, the game was cancelled.

This heralded a period of fear and confusion about the future. Papa wasn't as naive as others to think that the war would be over in two, three, or four weeks. When he got an opportunity to take us into evacuation, he phoned us at home and told us to take some underwear and pick up that small, packed suitcase, and get ready to leave. There were ten managers' families in our building, and I believe eight of them were Jewish. We all boarded the evacuation truck and headed to Kharkov via Poltava. This was on July 4, 1941. Papa stayed in Kiev. He refused to evacuate while headquarters was still there.

We drove to Kharkov, where we stayed with Lazar Isaakovich Korduner, my mother's cousin. He was Chief Engineer at the Kharkov tractor plant. He had worked on the plant's construction from the first day, and had bitter feelings when the plant was to be blasted. Katia, his mother, always waited up for him to return from the plant, and never went to bed until he got home. When the Germans were very close to Kharkov, Lazar received an order to blast the plant. He came home and literally fell onto Katia, crying. "Why are you crying?" she asked him. He replied, "Mama, I did something three hours ago that was almost like killing my own daughter." Later, Lazar became the Director of the Tagil tank plant and was awarded the Stalin Prize. He died in January, 1945, in Moscow, after his appointment to the position of Deputy Minister of heavy machine building.

Papa soon joined us. We went to Stalingrad, along with the family of Lazar Korduner. Papa got a job at the Stalingrad tractor plant. While we were on the train, we heard that the Germans had occupied Kiev on September 19, 1941. It seems to me that at that very moment I fully realized what a calamity this was for all of us. In Stalingrad we met Mama's relatives. They had miraculously escaped by boarding the last boat from Odessa. There were twenty-two of them, and our huge clan departed for Kirghizia. Lazar Korduner and his family went to Nizhniy Tagil. Prior to their departure, he provided us with winter clothes, coats and hats. He also arranged for our family to get on the barge sailing up the Volga. We learned there what hunger, dirt and fleas were like. People were boarding in crowds. I was squeezed by the crowd, and fainted. As I regained consciousness, I heard Polina Iosifovna shouting, "Careful! There is a child here!" Somebody felt sorry for me and took me to a cabin where sailors were staying. They gave me some hot water to drink. We reached Saratov, where we boarded a train: Uncle Kolia and his family, Uncle Arnold, Aunt Polina and us. I believe there were thirty-five of us there.

I was responsible for receiving bread at the evacuation points on the way. We were passing Buguruslan near Orenburg, when I saw a train taking Chechen people into exile. There were automatic guns in the windows, and people on the train screaming and dying with nobody to bury them. I will never forget this horrific scene.

In Tashkent we saw David, Papa's younger brother and his family. They had relatives in Tashkent and moved in with them. We headed for Frunze where we stayed until the end of the war. We arrived in Frunze on December 21, 1941. Although we were suffering a lot from fleas, we went directly to the concert of Klaudia Shulzhenko, a famous Soviet singer, at the Philharmonic. In Frunze we rented a room that we shared with the family of papa's sister. Our next door neighbor was a Russian man who had been arrested and sent there by Stalin. He gave shelter to Ivan Krauze. He became a gorgeous bass singer and a People's Artist of the Soviet Union. I also became closely acquainted with the family of Natan Rachlin, a famous musician.

We were miserably poor during the evacuation. Ziama Katsanov, an acquaintance from Kiev, helped Papa to get a job at a shop that manufactured colorings for lemonade. There was a bread shop there where we received bread in exchange for our bread cards, and my father had a card. My mother went to work as a nurse at the hospital. We were so poor that we celebrated the liberation of Kiev in November 1943 with two sugar beets that Papa received at work. My mother cut them into cubes and boiled them and we had this sweet water. I also remember Papa telling us that he was offered a slaughtered horse but he refused to accept it. He said he remembered the sweet taste of horsemeat from the period of the Imperialistic War (World War One) and he couldn't accept it.

I studied at the governmental secondary school #3 in Frunze. I still have the picture of our class at the prom party in 1943. Forty-eight out of our forty-nine member student class were in the evacuation, and almost all were Jews. After school I enrolled in the English Department of the Pedagogical Institute. Simultaneously, I studied the history of music, music literature, harmony and solfeggio and took piano lessons. My teachers were professors from the Moscow Conservatory: Vladimir Vlasov, Vladimir Ferre and Michail Arkadievich Rauchverger. They taught me for free. My only payment to them was the love and admiration I had for them which never faded.

In Frunze I dated a young man from Kharkov. After the liberation of Kiev, my fiancee's family and I went to Kharkov. I came to Kiev in January 1945 and began the second term in the Theory and History Department at Kiev Conservatory. In Kharkov I met my schoolmate Isaak Feldman. He was in love with me and proposed to me. It took me some time to make a choice between them while I was in Kiev. In the end I married Isaak Feldman, remaining friends with my friend from Kharkov.

My parents returned from the evacuation in 1946. Our apartment was occupied. Our furniture and all belongings were gone. But the worst of it was that my piano was gone, too. My father went to work as Deputy Director of the Polygraphy Headquarters. We received an apartment in the building of the Polygraphy factory. We got two small rooms with no kitchen or conveniences. My husband Isaak and I lived there until I finished the Conservatory in 1949. My father was supposed to receive an apartment in the house specifically built for the Polygraphy company, but when the building was completed, the Soviet of Ministers took few apartments for their employees, and we again failed to get an apartment. We got stuck in that basement for many years. My father suffered a lot because of it and died from a heart attack in 1958. My mother died in 1986 in that same basement.

In 1949 I finally felt myself a Jew. On April 13, 1949 a meeting was held at the House of Arts to discuss the issue of "rootless cosmopolites," as they were called then. Most of our teachers at the Conservatory were Jews: Liya Hinchina, my teacher before the war, and Maria Gelik, Frieda Azrova, Ada German, brother Abram, Matvey Rozenpud, and others. At this meeting Andriy Malyshko, a Soviet Ukrainian poet and many others posed accusations against the "rootless cosmopolites." I remember that Malyshko called Hinchin and Gelik "brood hens from the stinking nest of Olhovskiy." Olhovskiy was professor and a student of Asafiev, a great composer. He stayed under the occupation and later left for America. Hinchin and Gelik were his students. I was Deputy Secretary of the Komsomol Committee. The secretary of the committee was Zhenia, a young Russian man. The rest of the Komsomol Committee consisted of Jews: Lenochka Yampolskaya, Zhora Grinberg, etc. We were all stunned by the goings on in the meeting, and were in the cloakroom when we saw Mariana Gelik going downstairs. She had poor eyesight and had lost her glasses, and I saw that she was about to fall. It was clear that she and the other Jewish teachers were broken in spirit and their morale was destroyed. I helped Gelik to retrieve her coat and put it on. When I came to the Conservatory the next day, there was another meeting of the Komsomol committee which expelled me from Komsomol. There was only one vote against me, Zhenia's. He explained to me that because I had helped a cosmopolitan to put on her coat, that meant that I shared her views.

A few days later, I was expelled from the Conservatory. This happened a half a year before my graduation. All of the Jewish teachers were fired, of course. I felt terrible about what had happened. I stayed at home for three weeks. Then a friend came to see me. She said "Lialka, the Investigation Commission of the Central Committee of the Communist Party arrived in Ukraine. They ordered that you be reinstated to the Conservatory. So I was back at the Conservatory. Lena and I kept visiting Liya Yakovlevna Hinchin. We disguised ourselves in shawls and veils, but someone reported us to the Conservatory, saying that we went there to take classes. One day, Lena Yefremova and I were called to the office of Skoblikov, the Secretary of the Party unit. He interrogated me. "Do you visit Hinchin?" he asked. I answered, "Yes." "Are you writing your diploma with her?" "Yes." "Who else visits her?" It suddenly occurred to me to name people whom he couldn't punish because they were not Jews and who were very influential members of the Communist Party. I said, "Grigory Egorovich Veryovka and Eleonora Pavlovna Skrebchinskaya." He said, "You may go now."

He interrogated Lena in the same manner. When we were taking our state exam, there was a commission of twenty-four examiners sitting at the long table. Our first exam was on Marxism-Leninism. Lena and I had studied 103 items of their works. I got my exam card and spoke for one and a half hours. Then I fainted, and fell unconscious from the chair. As I regained consciousness, I heard Avievskiy, the Head of the Department, saying, "Give her some water and let her go on." I protested, "I don't need water, I shall go on answering." We passed all four exams and defended our diploma work with the highest grades. After it was all over, Boris Nikolayevich Liatoshynskiy, a Ukrainian composer and a very educated and intelligent man who was also declared a cosmopolitan, met us in the long, wide hallway and said, "I know that you will now take flowers to Liya Yakovlevna. Give my regards to her, and tell her that you passed your test in exactly the way appropriate for her students."

Liya Yakovlevna couldn't find a job in Kiev, so she left for Novosibirsk. Many cosmopolitans went to different towns and cities, looking for jobs. I got a job assignment in Zhytomir. I was married and Isaak and I were thinking of how to stay in Kiev. Papa got very ill and we were reluctant to leave him alone. But this was in the early 1950s when it was impossible for a Jew to find a job. I went to the Party Central Committee. My co-student was working there and I asked him to help me find a job in Kiev. He didn't. But my father-in-law had an acquaintance who was a conductor at the Kiev Military Communications College, and he helped me get a job as choirmaster in this college. I worked there for a year and a half and also took extra work at various shops until I got a job as a piano teacher in Kiev's Choreography School in 1954. Later, I also became a teacher of music theory and literature and worked there for 38 years. I was not very fond of my work, but I was doing it professionally. I preferred giving classes at home. My ex-students still bring me flowers on my birthday, or call me from New York, Paris and Berlin. They are like my children. I gave them all my love and shared my knowledge of the profession with them. I have no children of my own, because of medical problems.

I've lived my life with my dearest husband, Isaak Feldman. His father, Lev Grigorievich Feldman, a neuropathologist, was the director of a hospital during the war. My mother-in-law, Augustina, came from a wealthy Jewish family. She never worked outside the home. They had a very intelligent and educated family. My husband's family wasn't religious, and didn't observe any Jewish traditions.

During the war, my husband studied at the Navy College in Vladivostok, but was dismissed before his fifth year. He was there when the war with Japan began, and was on ships that sailed to America. Later, he finished a 3-year English course and also earned a university Law degree, studied at the Institute of Foreign Languages, in the English Department, and attended the Institute of Patent Engineers. He has studied all his life. About 15 years ago he got a job at a foreign company as a lawyer with his fluent English. About seven or eight years ago, he was sent on a business trip to New York. He spoke against "Lloyds," a very famous English company, and won the case that brought Ukraine $6 million. My husband still works.

I worked up until recently. I have traveled to France, Hungary, and the Netherlands, but have never considered emigration, and never to Israel. My attitude towards Israel is ambiguous. I have always been against mono-national communities. I have always been an internationalist, as I was raised in this way in my family and by the State. I respect this country and sympathize with its people, who are going through such hardships. Lately, I've become interested in Jewish traditions, but I think this interest came to me a little bit too late. Over the last ten years I have watched with great interest the restoration of Jewish life in Ukraine. Sometimes I read Jewish newspapers, or watch TV programs, but I don't think I will ever be able to go back to Jewish traditions, or to a Jewish way of life. I've lived through the period of atheism, and this can't be changed. Such was our time. I don't go to synagogue, nor do I celebrate Jewish holidays. I don't know these traditions. One must go to synagogue with an open heart and firm faith. I don't feel I can do this. It is wonderful that people have an opportunity to go back to their roots and learn about the traditions of their people, and be proud of their origin. In recent years, many Jewish organizations have been established in Kiev and synagogues have been opened. Many people attend them and this is wonderful.