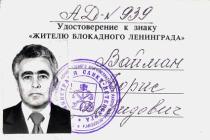

Boris Vayman

St. Petersburg

Russia

Interviewer: Kira Kuzmina

Date of interview: April 2007

I got acquainted with Boris Davydovich Vayman in his apartment situated in one of the new districts in the south of St. Petersburg. Beforehand we had a telephone conversation and I told him about my wish to interview him to know about his life and his family. Boris seemed to be suspicious and wanted to refuse at first. Then he decided to try, but still remained very strict and unfriendly. Nevertheless we made an appointment for a certain day. An elderly man opened the door. He was neat in his dress and looked young for his years, only his hands were trembling when he closed the door. Later he explained that it was after-effect of contusion which happened during the Great Patriotic War 1.

Boris lives together with his wife in a small and cozy two-room apartment. During our first meeting his wife was out. ‘She is always out, she always has something to do’ Boris commented. Five minutes after the beginning of our conversation Boris changed visibly, turning into a very friendly and kind person, and his severity evaporated. While talking he answered several telephone calls, and I understood that he was going to the theatre to watch K. Raikin's performance. [K. Raikin is a popular actor and producer in Russia.] So at the age of 81Boris lives active life filled with different cultural events.

To my mind, Boris Vayman is the most striking instance of a Soviet citizen. He studied at the ordinary secondary school, finished a technical school, and was a worker at a factory. He was a member of the USSR Communist Party, took part in Soviet demonstrations with pleasure, and celebrated Soviet holidays. He was lucky to come across manifestation of anti-Semitism only once in his life. Boris told nothing about a possible slightest (maybe inward) protest against the Soviet regime or against actions of the Soviet country leaders (except the Doctors’ Plot 2, when he was forced to listen to newspaper articles about doctors-murderers). He left an impression that he did not think about events in the country; he simply took things as they were, lived in the present, not analyzing the past and not thinking about the future.

My ancestors came from Belarus. My maternal great-grandparents were born in Kokhanovichi settlement near Vitebsk 3. They were small peasants. My great-grandfather was also engaged in tailoring. They were religious people and observed all Jewish traditions. They were not rich; they were some sort of well-to-do. Unfortunately I know nothing more about them. They lived long time ago, and my parents seldom recalled them.

My maternal and paternal grandparents were also born in Belarus (they lived in the neighboring villages), and my grandfathers were tailors, too. My maternal grandfather's name was Estrinov, but I do not remember my maternal grandmother's maiden name. My paternal grandfather was a tailor of top class, therefore his family was more substantial than the family of my mother. Members of both families spoke Yiddish, they also knew the Belarusian language. Certainly my paternal grandparents were religious people, too. Some time ago I had a photo of my paternal grandparents. From that photo I know that my grandfather wore a frock coat, boots, a hat. He had no payes, only a beard: it was not full, but small and neat. On that photograph my grandmother wore a scarf, and I am not sure if there was a wig under the scarf. She was very tall and slender, on that photo she was in a black dress with a small white jabot.

My parents told me nothing about their house, but I know that they kept hens and a small vegetable garden, where they grew vegetables. They had no assistants: nobody around them had. They observed all Jewish traditions very strictly: attended synagogue and went to shochet if they wanted to have chicken for dinner. The shochet said his prayers and the chicken was considered to be kosher. My grandfathers were members of no organizations or political parties: they were rather far from politics. They were persons of narrow interests, simple tailors - inhabitants of a Belarus village. I know that at their living place there were about 20 Jewish families and Jews lived together with Belarusians in harmony. Nationality never gave cause for contradictions.

I know almost nothing about my parents’ friends: most probably they were people from their surroundings, because they never left their place. I think that my grandparents never left for vacation. I also know nothing about their brothers and sisters: possibly they had none. You know, unfortunately we never talked about them. My grandparents died when I was a child (about 4 or 5 years old), therefore I do not remember their stories (if they really told me them): I guess I was too little to be interested in them. I remember only some sad stories my mother told about the attitude of Germans to people on the occupied territory, including Jews during the World War I (but no details). I also know nothing about my grandfathers’ army service.

I was born in Leningrad in 1926. I cannot tell you how much Leningrad was Jewish at that time. It was a great city where people of many nationalities (including Jews) lived together. There was no Jewish community regarding the city as a whole, but there was a small Jewish community at the Synagogue. Our family did not participate in the community life, but together with my father and mother we visited Synagogue during Jewish holidays. We lived round the corner, but visited Synagogue only on holidays: just to observe Tradition. In Leningrad Jews lived everywhere (in different districts of the city) and the question of organizing a separate Jewish community never came up for discussion. I can tell you nothing about Jewish schools in Leningrad: I attended an ordinary Soviet school. As far as I remember, before the war burst out (by that time I finished 7 classes) there was only one Jewish school at the Synagogue. So, I studied at an ordinary school, and all events that could be considered Jewish happened at home.

In Leningrad there were no typical Jewish professions: Jews were engaged in different business. For example, my father was a tailor at a fashion atelier, and accordingly he had friends mainly among tailors. Before the war I came across no manifestations of anti-Semitism. I recall some episodes from my childhood when my playmates told me something insulting, but I consider it to be caused by an emotion beyond definition: a word and no more. My parents were absolutely politically indifferent, they used to discuss some problems of everyday life in the kitchen and that was all. My parents were members of no organizations or political parties.

Certainly, I remember parades and holidays. On the 1st of May and on the 7th of November [state holidays in the USSR] we (together with my father) participated in demonstrations. [In the USSR demonstrations of many millions were usually organized during state holidays; people had to express their loyalty to the Soviet regime, demonstrate achievements.] It was my favorite occupation, I went on taking part in demonstrations till 1990s. It was especially pleasant to go on demonstration on the 1st of May when it was warm and sunny. People listened to radio broadcasting and sang cheerful songs. For instance, I remember the song about morning light that paints walls of the ancient Kremlin and wakens our glorious Moscow. That song was a necessary attribute of Soviet demonstrations.

It was my mother who used to go to the market to buy food. Usually she went to Sennoy or Troitsky market. She used to buy milk at the same milkwoman. Having got his month salary, father used to buy a box of tangerines every month. I remember the price: every small tangerine cost 20 kopecks, each big one 40 kopecks. Unfortunately he could not afford it more often than once a month.

My mother Badola Vayman (nee Estrinova) was born in Belarus, in Kokhanovichi village. My father David Vayman was born in Belarus, too (in the neighboring village, but I do not know its name). Mother was born in 1895, and father was younger: he was born in 1898. Both mother and father studied in cheder and finished it. Besides my father was a tailor’s apprentice where he learned to sew and became an expert. Mother had got no profession, she was a housewife and took care of children. Their mother tongue was Yiddish; they also spoke Russian and Belarussian (mother knew German, she managed to learn it during WWI German occupation).

I do not know how they met each other. But I know that they had both a standard secular marriage ceremony and a ceremony in the synagogue. Before the revolution of 1917 people considered marriage according to religious traditions to be legal, and they went to civilian state registry offices only to settle marriage articles. [Registry offices were obligatory in the USSR.] They got married in 1922.

They used to wear up-to-date clothes of city style, no national Jewish clothes. Our family members were people of moderate means. We were 3 brothers, we were always well dressed, booted and satisfied with food, but at the same time we denied ourselves every luxury.

Before the war burst out, we lived near the Synagogue in the separate two-room apartment with central heating and water supply. There was only one trouble: on a lower floor there was situated a city laundry. Washing was arranged in large wooden tubs; hot water evaporated and exhalation got into our apartment through the open windows: it was absolutely unbearable. At last, parents managed to change that apartment. They gave money (my mother’s brothers helped them financially) and we moved to another apartment near Fontanka River.

There we also had two rooms, a hall, a kitchen with a stove; there was no bathroom, no central heating. That was the way we lived before the war burst out: mother, father and 3 sons. We had no assistants: we could not afford a servant. Mom did the housework and took care of her sons herself. At home we had many books: only secular literature. For the most part it was Daddy who read the books. Having come home after his working day father liked to read Russian and world classical literature: Pushkin 4, Dostoevsky 5, Tolstoy 6, Cervantes [Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616) was a Spanish writer] and certainly Sholem Aleichem 7. He never advised me regarding books to read. At school where I studied, our teacher of literature was a distant relative of Gorky 8. She managed to implant the love of reading and collecting books in her pupils. We all loved her very much. After the end of the war in 1948 I arrived in Leningrad and we (all her former pupils who remained alive) gathered at her place. We visited her many times. Parents did not go to library, because it was possible to buy any book you liked. Those books circulated among relatives and friends until they were thumbed out of existence.

Parents did not observe all Jewish traditions, but they celebrated Jewish holidays. They used to gather at one of Mom’s brothers or at our place. Father knew prays and said them on holidays. Parents never were active members of the Jewish community: they were not interested in politics, organizations and parties. The only organization my father joined was a labor union of sewers: it was obligatory.

My father was a participant of the World War I. He served as an infantryman in Grodno [a city in Belarus]. He was there until the end of the war. In 1941 when the Great Patriotic War burst out, he was drafted during the first days, and 2 or 3 months later we received a notification about his death. In fact he was considered to be missing, but till now we know nothing about his fate.

We had very good neighbors and I remember their surname till now: the Korsunskies. They were Russian, they were very kind, and we never had a difference about nationalities. Mom liked them very much. I also made friends with our neighbor Polyansky: he was 2 years older than me. By the way, much later there happened a marvelous coincidence: when the war was finished, I was moving to the Far East and suddenly at a railway station near Moscow met Polyansky. You know, we never met again. I know nothing about him and it was hard to imagine his life after our meeting, because they were on their way back from captivity.

My parents made friends with both Jews and Russians: there was no difference for them. All our neighbors loved my father very much, because he was very kind, the kindest person I knew. Mother often criticized him severely for his kindness, because he was always ready to help, to repair clothes, etc. Daddy had no enemies or evil-wishers. Father made friends with mother’s brothers. They both lived not far from our place.

Summer vacations we (children) used to spend with our Mom in Belarus at Mom’s sister Dasha. Here I’d like to tell you that besides 3 sons, our parents had got 2 daughters (our sisters), but unfortunately they both died at a very young age. One of them (Bella) died in Belarus during our summer holiday in 1940. She was only 1 year old. She ate some grass and fell ill of dysentery. Doctors did not manage to save her life. And our 2nd sister Tanya was the eldest: she was born in 1924. But in 1929 she hit her head somehow and died. In our family only the boys remained alive. We spent our summer vacations in Belarus, and father worked all the time. Rarely he went for vacation to a recreation house (his labor union gave him permits) in Kislovodsk 9 and to sanatorium in Sestroretsk [a suburb of St. Petersburg].

My aunt Dasha (Mom’s elder sister) died together with all her family during German occupation. People suggested her to evacuate, but she refused: she had been told that during the World War I Germans did not persecute Jews. Mom also had 2 brothers: Roman (born in 1893) and Konstantin (born in 1902). Her brothers were tailors, too, but they were tailors of a very high class. Konstantin, the younger brother left for front line, was badly wounded and demobilized. He lived in Leningrad and died in 1954. Roman, the elder brother also participated in war (he served in auxiliary arm). He was demobilized after the end of the war and lived in Leningrad, too. He died there in 1980 at the age of 87. Roman studied at the Textile College in the same group with Kossygin, the future chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers. When Kossygin came to Leningrad, he usually gathered his fellow-students to have a talk. I do not remember where Mom’s younger brother studied. Roman had got a son, but he died at a very young age in 1929: his nurse did not take good care of him (he fell down) and told nothing to his parents. And Konstantin had got 2 sons and a daughter. At present his daughter is 82 years old, she is a doctor (graduated from the 1st Medical College in Leningrad). Konstantin’s younger son has already died, and his 2nd son is now a pensioner and lives in Sverdlovsk [a city in Urals]. He was a nuclear physicist (graduated from the Leningrad Polytechnical College) and worked at Sverdlovsk Nuclear Center.

Parents communicated only with Mom’s brothers. Families met on Jewish and Soviet state holidays (every family received guests in turn), but on Pesach we met only at Mom’s elder brother: it was agreed.

I was born on October 1, 1926 in Leningrad. I never attended kindergarten, I was at home with Mom. While I was little I used to spend much time outdoors: I played in the court yard. The court yard was rather small. Its gate was usually closed, therefore it was not dangerous for a child to be there (and Mom kept an eye on me from the window). Later I became a schoolboy. First 3 years I studied at school №4 and then changed it for the school №20 (it was situated near the Maryinsky Opera and Ballet Theatre. [The Maryinsky Opera and Ballet Theatre was founded in 1783 in St. Petersburg.]

Both schools were ordinary Soviet schools, and I do not remember why I changed one for another. My favorite lessons were literature, chemistry and physics. We all liked our teacher of literature very much. Our teacher of chemistry was not extremely good in teaching, but she was so charming that all boys of our class were in love with her. Of course there were teachers whom we did not like, for example a teacher of manual training was a terrible pain in the neck. We also were allergic to our teacher of mathematics. During my school years I never came across manifestations of anti-Semitism. After school I was occupied in no additional studies.

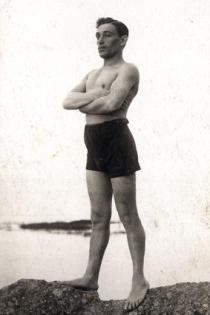

At school I had a friend (a Jew); he was a year older than me. We were good friends, often visited each other and our parents were acquainted. His parents were well-to-do, he had got a good camera and we took photographs and developed them - it was very interesting for me! After school we liked to go to the cinema. If I got good marks at school and behaved well, Mom gave me 25 kopecks for cinema. We liked to go to the RECORD cinema (it was situated in Sadovaya Street). We also frequently visited the so called Sea Crew Club where they arranged festivals. I did not go in for sports regularly, but liked to kick the ball about in the street.

During our summer vacations in Belarus I had many local friends, but in winter we did not keep in touch. Several times we rented dacha 10 in Vyritsa [a suburb of Leningrad] for summer and several times I went to a pioneer camp 11 in Siverskaya [a suburb of Leningrad]. That camp belonged to the labor union of sewers. There were a lot of circles: poker-work and joinery for boys and needlework for girls. For all children they arranged sports games, competitions, and walking-tours.

My younger brother’s name was Naum. He was born in 1929. He finished the Technical School of Soviet Trade. [Technical School in the USSR and a number of other countries was a special educational institution preparing specialists of middle level for various industrial and agricultural institutions, transport, communication, etc.] As he was only 12 years old when the war burst out, he was not drafted and we remained in Leningrad during its blockade 12. As soon as it was lifted, we (together with Mom) left for evacuation. After the end of the war he worked in the Leningrad trading port as a foreman. He had got a daughter and a granddaughter. Naum died in 1986.

The youngest brother Anatoly was born in 1935. He finished a secondary school, served in the army. All his life long he worked at the factory of radio engineering equipment, he was a first class expert. He also had got a daughter, she works as a financier. She has got a son, he is already 22 years old. Anatoly died in 2005 (15 days before his 70th anniversary).

At home we only celebrated Jewish holidays. We attended synagogue (with parents) only on holidays, too. I studied at the ordinary school, therefore I learned neither Hebrew, nor religious traditions. Parents never taught me observing traditions, but I watched them celebrating holidays and studied. Chanukkah was my favorite holiday and I’ll explain you why: on that holiday people give presents to each other and frequently give money; when on Chanukkah we visited our uncles they always gave me money. That is why I loved that holiday very much.

Before the Holocaust I studied at school. During the Holocaust I was in the besieged Leningrad, then at the Railway Transport School in Omsk. Later we together with my Mom and brothers evacuated to Kazakhstan, and therefrom I left for front. Fortunately Holocaust affected neither me nor my family. We got to know about it much later.

We went in evacuation to Kazakhstan (to Kokchetav) when the blockade of Leningrad was lifted. There Mom got fixed up in a job at a stud farm. I do not remember what kind of work she did, but I can tell you that she received very good salary: we bought a cow and were provided with milk. It happened in 1943 when I was 16 years old. As I was brought in the spirit of patriotism, I went to a military registration and enlistment office (in secret from Mom) to submit an application for sending me to the front line. Officers from the local military registration and enlistment office told me that I was too young, that it was necessary to grow up and put me out of doors. But I was very persistent and at last at the age of 16 years and 8 months they took me to the army.

By the way, earlier on our way to Kokchetav a tragedy happened: I was left behind the train in Kirov (now Vyatka). Mom sent me to buy a glass of berries at the railway station, and at that time the train left. I remained alone without documents and money. The commandant of the railway station took pity upon me and placed me in the hospital: you can imagine what a child from the besieged Leningrad looked like!

I do not remember how much time I spent in the hospital. Later they sent me to Omsk [a city in Siberia] by train. There local authorities gave me new documents (restored according to my words) and sent me to the Railway Transport Technical School to become a machinist assistant. During that period of time I knew nothing about my Mom and brothers, but I knew the address of the wife of my mother's brother: she and her children were evacuated to Sverdlovsk. I wrote her a letter and she informed me where Mom was. That was the way I found mother in Kokchetav. As my technical school was a military organization, they refused to let me off. And do you know what an idea came to my mind? I turned out to be clever enough to ask Mom to send me a document that she was near death! But Mom managed to send me such document (she even managed to make the document attested!).

That was the way I arrived in Kokchetav to my Mom. There I secretly started visiting the local military registration and enlistment office. I did not want to come back to Omsk to the School I did not like. At last they sent me call-up papers and Mom had no choice but to let me go (by the way, she never got to know that it was me who initiated the process). The military registration and enlistment office sent me to the Aviation Military School. I was going to become an air-fitter. The school was evacuated to Petropavlovsk (in Kazakhstan) from Leningrad. There I studied half a year. Of course they did not teach us to be mechanics, they simply prepared us for war: we practised shooting, dug entrenchments, etc. In September 1943 we were sent to Vitebsk region and my soldier’s life started.

I sustained my first shock in entrenchments full of water: at night the water had iced and my feet became pieces of ice, my overcoat turned into ice armor.

At that time we (consisting of the 3rd Belarusian front) were going to assume the full-scale offensive. I got to the division #17 (to the flame thrower platoon). I’ll explain you what it meant. I had to carry a knapsack weighing 6 kg. Inside the knapsack there was a napalm-cylinder weighing 5 kg. In total I carried 13 kg on my back and a gun (flame thrower) in my hands. I pulled the trigger and flame 50 meters in length burnt everything on its way.

The front passed to the offensive and started its fight for liberation of Belarus. Our platoon used to join special storm-troops and we smoked Germans from their covers.

We fought our way through Belarus and crossed the border of Lithuania. In Vilnius during street fighting our weapon was very useful: we burnt fascists out from the houses. There I was shell-shocked for the first time: I was running across the street and fell down. Fortunately I fell behind a wall; otherwise I would have been killed. I regained consciousness in the hospital. The contusion appeared to be very serious: I lost my hearing and became speechless. It was terrible to think that it was for ever. Treatment took 3 months, but my young and healthy constitution helped me to come through the illness. Fortunately both speech and hearing were back to normal. That contusion happened on July 10, 1944. Therefore Vilnius was liberated without me (on July 13).

3 months later I recovered and got back to my platoon (by that time it approached the border of Eastern Prussia). We passed to the offensive on January 13. We quickly went through 3 lines of German entrenchments, but on the 4th one a mortar shell exploded and I was wounded in the leg. I fell down into entrenchment. The wound was not terrible: the bullet missed the bone. I spent 17 days in the front hospital and again got back to my platoon. We participated in the storm of Kongsberg 13.

We burnt enemies out from houses, pillboxes and fortifications. Now I realize that those days were terrible, because we felt the near end of the war and were keen to meet the victory alive. In April we liberated Konigsberg and stopped: we did not move farther, because the war was coming to its end.

But for me the war was not finished, because the war with Japan 14 began. In June they sent us to the Far East by trains. We got off in Chita and went at the march through Mongolia. It was extremely hot there (about 30 degrees centigrade), our way ran through sands. Because of the hot weather, we moved only at nights. They drew a rope between the endmen to prevent soldiers leave the column and be lost in the dark steppe or get under the tracks of tanks (tanks were moving along the roadsides).

So from Chita we moved through Mongolia, through Great Khingan Mountains, reached Manchuria [China] and met the Japanese army. It appeared to be a great surprise for the Japanese; they began to surrender, and we captured Port Arthur [a port in China]. On September 4 Japan capitulated. I went on serving as a soldier in Port Arthur. First I served in the regiment, then in the commandant's platoon (the commander’s guard). Later the commander made me his personal driver. In 1948 he gave me leave of absence and I went to Leningrad, but came back. I served there till 1950 and at last I received my demobilization documents … but at that time a war between Northern and Southern Korea burst out. We had to convoy tanks for Northern Korea. We reached the place, handed tanks over to the local military and moved to Vladivostok [the USSR port on Pacific Ocean] by a warship. From Vladivostok I moved home. So in fact my service ended only in 1950.

I returned to our apartment near Fontanka River, which remained safe. Mom came back from evacuation in the beginning of 1945. It was possible for the citizens to return to Leningrad only if they had a document that your former living space remained safe. Her brother sent her an invitation and the document, therefore she returned to Leningrad together with my brothers. I saw Leningrad not right after the war, but only in 1948 (being on leave); therefore I do not remember ruins or other effects of war. By 1948 Leningrad was already repaired (for the most part) and put in order.

I returned home and became a metalworker at the Krasny Treugolnik factory. [The Krasny Treugolnik factory produced rubber goods.] I came there on November 1, 1950.

I never discussed the question of emigration and never wished to emigrate: in this country nobody ever griped me, I had no conflicts with local authorities. I was a member of the USSR Communist Party. Probably I was not a 100-percent communist, but I really believed in the bright future. Nobody from my close friends emigrated. Some of my acquaintances left for the USA. I took their departure hard: I felt like a piece of my body broke away, but the idea of leaving never came into my head.

I came to the Krasny Treugolnik [‘Red Triangle’ in Russian] factory in 1950 and worked there till 1991 (until I retired on pension). At first I worked as a metalworker, then as a foreman, later I became a master and then a shift chief. Already being a factory worker, I finished the Leningrad Welding Technical School, and later the Technological College (faculty of the controlling and measuring apparatus). Naturally I was a part-time student.

I came across manifestation of anti-Semitism in 1953 (for the first and the only time in my life) during the time of Doctors’ Plot. Our director liked to read aloud articles about the so-called doctors-murderers, and every time he came to me personally and invited me to listen. He insisted that I occupied one of the front seats and kept vigilant watch on me. I had to listen to those crazy articles, lampoons, and terrible dirt. Till now it is hard to recollect. His attitude to me affected my career. When I worked as a foreman, I was invited to become a head of rationalization department. It was a prestigious position, highly paid. There it was necessary to work with new projects; I liked it and wanted to be engaged in it very much. But the director rejected the suggestion. Later Stalin died and the dust settled. The only thing in my life affected by anti-Semitic laws and moods was my wish to go abroad for touring: of course they did not let me out. So first time I went abroad (to Yugoslavia) was in 1968. After that, touring became easier and I visited Austria and Italy.

I never chose friends according to their nationality. It was not important for me: I am an internationalist.

I got married in 1953. My uncle acquainted me with my future wife. She was 1 year older than me. She was born in 1925 in Leningrad. Her name was Dora Tantvorg. She was a highly educated woman: she graduated from the College of Foreign Languages and knew 2 languages (English and German). She worked as a college teacher. She had got 2 brothers. We lived together 6 years and then got divorced. We have got a daughter.

Later I got married for the second time. We got acquainted at the Krasny Treugolnik factory. My second wife’s name was Ludmila Spitsnadel. She was born in 1931 in Leningrad. I know that her father came from Latvia. We never discussed her nationality: according to her passport she was Russian, but her maiden name gives different information. She graduated from the Pedagogical College named after Hertzen. All her life long she was a trade-union worker at the Krasny Treugolnik factory (she was the head of a cultural department). We have got no children.

My daughter Diana was born in Leningrad in 1954. She studied at an ordinary school. We brought her up according to Soviet traditions. For the most part her grandmother and grandfather took care of her. Certainly she knows that she is Jewish, and she considers herself to be a Jewess, but we never accented it. She graduated from the Technological College. At present she works as a head of technical department at LENGAZ. [LENGAZ was the Leningrad municipal gas economy.] She is married, but they have got no children, and accordingly I have got no grandchildren. My family does not observe Jewish traditions: we do not celebrate Jewish holidays, do not attend the Synagogue. All those traditions are dead customs for us. Among my friends there are both Jews and Russians. Of course all the time I was in touch with my Mom, her brothers and their children (i.e. my cousins), and of course with my brothers. We used to meet at somebody’s place to celebrate state holidays and family celebrations.

Stability came into my life after 1950s. I had got a family, a job. I made a good salary and became an independent person. In 1953 Stalin died and the unpleasant situation at my work improved. The intensity of propagation decreased.

Rupture of diplomatic relations with Israel affected me the following way: in 1968 I was going to Yugoslavia as a tourist. My name had to be approved by the factory administration. Our director invited me for a talk and asked me about my attitude to the conflict between Palestine and Israel. I answered diplomatically that I thought Israeli territories should belong to Israel, and Palestinian ones to Palestine. The administration members smiled ironically and approved my candidature. That was the way I went to Yugoslavia.

I never visited Israel. I had an opportunity to go there, but I did not take the occasion: my health forbade my coming and I did not want to change the climate. I got to know about death of several persons who left for Israel and could not endure the rigors of local climate. It frightened me very much, and I refused to go.

As far as I know my daughter never came across manifestations of anti-Semitism. Her nationality was of no significance during her entrance exams at College or later at her work.

I have no relatives abroad. Some of my acquaintances left for the USA, but it happened about 8 years ago, therefore it was not dangerous for me to be in touch with them (though earlier it could be extremely dangerous).

I was very glad to witness changes in the world political situation. I was especially glad that the Berlin Wall was destroyed. [Berlin wall was erected in 1961 to divide Western part of Berlin from the Eastern one. It was destroyed in 1989. It was symbolical that its concrete was used to construct highways of the united Germany. It was demolished in 1989.] We used to take a jaundiced view of Germany, though today it is an absolutely different country with different principles. They feel guilty of both Holocaust and war and they want to be purged of sin. At present they are absolutely different people and it is necessary to be understood.

In general I cannot say that my life changed much after 1989. About 10 years ago I started taking part in activities of the Jewish Organization of War Veterans. It helps Jews to observe traditions. They behave tactfully: celebrate not only Jewish holidays, but for example the Victory Day (on May 9 they usually rent theatre premises and invite us there). Jewish amateur groups use to take part in great concerts devoted to the Victory Day: they dance, recite poems, etc. The concerts are usually very interesting.

I receive food packages from the Hesed Avraham Welfare Center 15. Some time ago they gave us large packages with a lot of food, but now they are much smaller (unfortunately).

I never received any financial assistance from Switzerland, Germany or Austria.

I was lucky that during my long life I came across manifestations of anti-Semitism only once, but I remember it till now.