Ernest Galpert

Uzhgorod

Ukraine

Date of interview: April 2003 Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

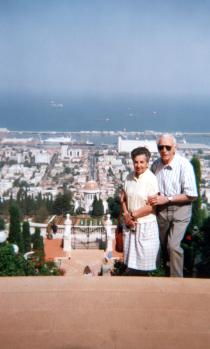

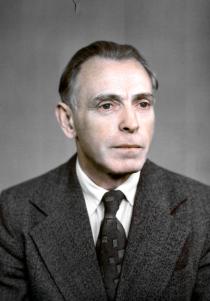

Ernest Galpert is a tall slender man, quick in his movements. Although he will turn 80 in June one cannot call him an old man. He has a straight bearing and the figure of a young man. He has thick hair, bright and cheerful eyes and a nice smile. The name of Ernest is written in his official documents, but he is called Ari, affectionate for Archnut. His children and the rest of his family call him Ari-bacsi ['uncle' in Hungarian]. He speaks fluent Russian with a slight Hungarian accent. The Galpert couple is very hospitable and open. They have lived in this two- bedroom apartment for over 40 years. It's in a building built back in the 1920s during the rule of Czechoslovakia, in the old center of Uzhgorod. They have heavy old furniture in their apartment, and keep their apartment very clean. Ari's wife Tilda is a real keeper of the home hearth. Ari and his wife make a loving and caring couple. They are always together and Ari even joked that since his wife has joined a club in Hesed he will have to accompany her there. There's still a lot of love between them.

Family background

Growing up

During the war

Post-war

Glossary

My paternal grandfather and grandmother Galpert lived in the village of Nizhniye Vorota [60 km from Uzhgorod], Volovets district in Subcarpathia 1. I knew my grandparents very well. My grandfather, Pinchas Galpert, was born in Nizhniye Vorota in the 1860s. My grandmother Laya was born in the 1870s. I don't know the place of her birth or her maiden name. I've never met any of their relatives. My grandfather finished a yeshivah. I don't know where it was located. Their children were born in Nizhniye Vorota. My grandfather and grandmother had eight children. My father, Eshye Galpert, born in 1896, his younger brother, Idl, and his sister whose name I don't remember, stayed with their parents. My father's sister moved to her husband when she got married. I don't remember her. The rest of my grandparents' children also left their parents' home when they grew up. One of my father's older brothers, whose name I don't remember, moved to Bogota, Columbia. His other brother Moishe Galpert lived in Michalovce, in Slovakia. My father's older sister emigrated to Switzerland. My father's brothers Yankel and Berl moved to Palestine in the 1920s after training in hakhsharah camps 2 before World War I. Those were training camps for young people where they prepared Jewish children for life in Palestine.

In the early 1900s my father's family moved to Mukachevo. My father actually grew up in Mukachevo. After moving to Mukachevo my grandfather went to work at the Jewish burial society [the Chevra Kaddisha]. My father's younger brother Idl was his assistant. Idl lived with his parents before he got married. My grandfather was a Hasid 3. I remember him when he was an old man. He had a gray beard and payes. On weekdays he wore a black suit and a big black hat, and on Saturday he wore a long black caftan and a yarmulka with 13 squirrel tails that Hasidim used to wear on Saturday and Jewish holidays. [Editor's note: The hat that Hasidim usually wore on holidays is called a streimel.] My grandmother was a housewife. She wore black gowns and a black kerchief. She was very nice and caring and loved her numerous grandchildren. My grandmother died at the age of 60, in 1937. Now, at the age of 80, I understand that she wasn't that old, but at the time when I knew her, she seemed very old to me. Perhaps, my grandmother got prematurely old missing her children that lived far away from their parents' home.

My father's family was very religious. It couldn't have been otherwise in a Hasidic family. My grandfather went to the synagogue every day and so did his sons after having their bar mitzvah. They observed Sabbath and Jewish holidays at home and spoke Yiddish. My father and then his younger brother Idl finished cheder and went to study in a yeshivah in the town of Nitra in Slovakia. This part of Slovakia belonged to Austria-Hungary then. My father told me a little about the yeshivah where he studied. There were mainly young men from poorer families who came to study in the yeshivah from other towns. Students from wealthier families had meals in restaurants, but those who couldn't afford it had meals in Jewish families. My father told me funny stories about such dinners. One day he came to one family and another day somebody else invited him. Some families treated my father arrogantly, some friendly, and others with respect. By the way, when I was a child, we also invited students from the yeshivah in Mukachevo to dinner. Every Tuesday Chaim, a poor Jewish student, dined with us, and mother always tried to cook something special and make Chaim feel at home.

During World War I my father was recruited to the Austro-Hungarian army [the so-called KuK army] 4. At that time religion played an important role in the army and in life in general. The military could go to the religious establishments of their confessions when time permitted it, of course. Jews went to the synagogue on Saturday and Christians could got to their church on Sunday. Occasionally local Jewish families invited Jewish soldiers to Sabbath or other Jewish holidays. In their military units they had an opportunity to have kosher food cooked for them. My father was captured by the Russians and taken to Tver region in Russia. He told me about his captivity. He spoke of the Russians kindly. The landlords took prisoners of war to work for them. They kept the prisoners in good conditions and provided good food for them. My father was working for a landlord when in 1917 the Russian Revolution 5 took place. Then there was the Civil War 6. When the war was over in 1918 the Bolsheviks released all prisoner of war captured by the tsarist army and my father returned home to Mukachevo. Shortly after he returned he married my mother.

My mother's father, Aron Kalush, died before I was born. The Jews of Subcarpathia came from Galicia, Western Ukraine, for the most part. Many people's surnames derived from the names of the towns or villages they came from. There were many Jews who had the last name of Debelzer or Bolechover, which were the names of towns in Galicia. I think that the last name of Galpert derived from the town of Galper. There's nobody else with the last name of Galpert in Ukraine, I've only heard of the last name of Galperin. I can only guess that when their ancestors moved to Austria-Hungary, their family name was changed in German or Hungarian manner. Grandfather Aron's family must have moved from the town of Kalush, but that's only my guess. I don't know the exact place of birth of my grandfather. He was born in the 1860s. He was a glasscutter.

My grandmother, Laya Kalush, was born in Subcarpathia in the 1870s, but I don't know her exact place of birth. I don't know her maiden name either. She was a housewife. My mother and her sisters and brothers were born in Mukachevo. My mother was the oldest in the family. She was born in 1894 and named Perl. The rest of the children were born after an interval of one to two years. My mother's sister Ghinda was the second child. The third was Yankel and the youngest in the family was Nuchim. My mother's family wasn't as religious as Hasidic families, but they went to the synagogue on Sabbath and Jewish holidays, the men prayed every day at home and they, of course, observed the kashrut. All children were raised Jewish. The family spoke Yiddish at home and Hungarian to their non-Jewish neighbors.

There was an epidemic of the so-called Spanish flu in Subcarpathia during World War I. Many people died of this flu in Mukachevo. To prevent the spread of this virus people's corpses were buried in pits filled with liquid chloride in the Jewish cemetery. They also buried people that were still alive if they believed them to be hopelessly ill. My mother's younger brother, Nuchim, died that way. My grandfather died from the flu and Nuchim was still alive when they took him to the cemetery in 1914.

After Grandfather Aron died and after the mourning was over, my grandmother remarried. Her second husband was a Jewish widower from Michalovce in Slovakia where my father's brother Moishe lived. All I know about my grandmother's second husband is that he was a shochet. I don't remember his name. My grandmother visited us several times for a few days. I remember that she was an old woman wearing a black dress and a black kerchief. My grandmother and her husband perished in 1941 during World War II. Jews from Slovakia were taken to Auschwitz. In 1939 the fascists [Germany] attacked Poland and built concentration camps there. There were only rumors that Jews were taken to Auschwitz from Slovakia. My parents knew that my grandmother and her husband were taken to a concentration camp, but they didn't share this knowledge with us. However, we, kids, understood that something bad had happened. My mother kept crying repeating, 'How is Mother? How is Mother?' In 1944, when the Jews from Subcarpathia were taken to Auschwitz, we didn't have any idea what was happening there. We thought it was an ordinary labor camp, although in labor camps inmates also died from diseases or starvation. Nobody knew that it was a death camp. My mother kept writing letters addressed to grandmother, but we never heard from her and my mother was deeply concerned. Finally she received a letter from my grandmother's neighbors. They wrote that my grandmother and her husband perished in Auschwitz.

I have dim memories about my mother's brother Yankel. He perished during World War II, but it happened before the Germans began to take Jews to concentration camps. My mother's sister Ghinda got married and moved to her husband's town, to Vynohradiv [80 km from Uzhgorod]. I remember her well since I often spent my vacations with her family. Ghinda's husband was a tailor and she was a housewife after she got married. They had six children. One daughter died in infancy. Ghinda's children were about my age. The name of Ghinda's older daughter was Surah. One of her daughters, my niece Olga, died in Israel recently and her second daughter Perl lives in Canada. Ghinda's sons Aron and Yankel were in a concentration camp. After liberation from the camp they moved to Israel. They lived in a kibbutz. Aron died in the late 1980s and as for Yankel, I've lost contact with him. Ghinda's other daughter, whose name I don't remember, lived in Budapest, Hungary. She died in the 1970s. Ghinda had diabetes. She died in 1940. Yankel, Ghinda and her family were religious. My mother was the only survivor of all her brothers and sisters when the Germans began to deport people to concentration camps.

I think my parents had a prearranged marriage since it was common practice with Jewish families to address matchmakers - shadkhanim, regarding this issue. My parents had a traditional Jewish wedding in 1919 when Subcarpathia belonged to Czechoslovakia. My mother told me how many geese were slaughtered and who their guests were, but I can't remember any details. I was a boy then and took no interest in such things. They had a chuppah at home in the yard and the rabbi from the synagogue that my father attended. The rabbi conducted a traditional wedding ceremony and then the newly-weds had to drop a plate and step on it with their feet to break it. Now they break a glass, but in the past it was a plate. When the plate broke the guests shouted 'Mazel Tov!' and sang wedding songs. Then they danced. The newly-weds danced the first dance and then there were mitzvah dances where guests took turns to dance with the bride. Every guest paid for the right to dance with the bride. The rich always demonstrated how much they were putting on a plate and the poor quickly dropped money so that nobody could tell how much they put down. That's what my mother told me.

After the wedding my parents' relatives helped them to buy a house. The Jews in Mukachevo lived in the center of the town. There was a Jewish neighborhood in Yidishgas ['Jewish Street' in Yiddish] and there were also Jewish houses in other neighborhoods. My future wife, Tilda Akerman, also lived in Yidishgas and we lived in the neighboring street where Jewish houses neighbored non-Jewish houses. There was no place for growing vegetables near the house. Land was expensive in the central part of the town. Farmers lived and grew their products on the outskirts of the town. My paternal grandparents lived near us on Danko Street.

My father had a small store in the biggest room in our house with an entrance from the front door. There were three rooms and a kitchen in the house. We entered the living quarters through the store. My father sold all common goods in his store. He worked in the store alone, there were no other employees. He opened the store early in the morning. In the early afternoon he closed it to go to the synagogue and when he returned he opened his store again to work until evening. Occasionally, even when the store was closed some customers asked my father to sell them what they needed and my father didn't refuse to serve them. He had Jewish and non- Jewish customers living in our street. We, children, also helped him in the store. My father earned enough for the family to make ends meet. We were neither rich nor poor. We didn't starve and could afford to support the poor on Thursday so that they could have a decent Sabbath. To help the poor was considered to be a holy duty, a mitzvah. On Thursday contributions for the needy were collected at the synagogue and my father always gave some money to the collectors.

There were three children in the family. My sister Olga was born in 1920. Her Jewish name was Friema. I was born on 20th June 1923. I had the name of Arnucht written in my Czechoslovak birth certificate. I was named after my maternal grandfather Aron. During the Hungarian rule [1939-1945] I was called Erno and during the Soviet rule [1945-1991] I became Ernest, but my close ones always called me Ari. My younger sister, Toby, was born in 1925. She is called Yona in Israel. Yiddish Toyb for Toby means 'dove' and dove is Yona in Hebrew.

Mukachevo was a Jewish town. It was even called 'little Jerusalem' and it was a center of Hasidism. Jews constituted over half of the population of Mukachevo. There were over 15,000 Jews in the town. There were five to six children in Jewish families. The Austro-Hungarian authorities were tolerant towards Jews. Jews enjoyed equal rights with others and when in 1918 Subcarpathia joined Czechoslovakia life became even better. The president of Czechoslovakia, Masaryk 7, and then Benes 8 allowed the Jews to hold official posts. Religion was appreciated at all times. On Saturday the Jews went to the synagogue. All stores and shops were closed. Their owners and craftsmen were Jews. Non-Jews got adjusted to this way of life. They knew very well they couldn't buy anything on Sabbath and did their shopping on Thursday and Friday.

Many Jews owned craft shops and factories. Trade was mainly a Jewish business. Jews also dealt in timber sales. They managed woodcutting shops from where they sent timber to wholesale storage facilities where customers could buy all they needed beginning from planks and beams for construction and ending with wood for heating. There were wealthy Jewish families, but the majority of them were poor, of course. There were Jewish craftsmen: tailors, shoemakers, carpenters and cabinetmakers. The barbers and hairdressers were also Jews. Most of the doctors and lawyers in Mukachevo were also Jewish. Non-Jews were mostly involved in farming and held official posts.

There was a specific profession that only women did. Every married Jewish woman wore a wig. The moment she stepped out of the chuppah she had her head shaved and put on a wig. [Editor' note: Ernest doesn't remember correctly, the custom is that the bride's head is shaved before going to the chuppah.] Therefore many women made wigs in Mukachevo. They sold their wigs in Subcarpathia and had orders from Czechoslovakia and Hungary. This profession required special skills and mothers began to train their daughters at an early age.

Many Jews lived on what the Jewish community paid them. What I mean is that they were working for the community. There were about 20 synagogues and prayer houses in Mukachevo. There was a rabbi and shammash in each synagogue. There were many cheders where melamedim and behelfers, their assistants, worked. Children went to cheder at the age of three and needed additional help. There were specialists in circumcision called mohels. Some were selling religious books and accessories for prayers or holidays.

There were two shochetim in Mukachevo. They worked in a building near the synagogue. The Jews mainly ate poultry: chicken and geese. They took their poultry to a shochet to have it slaughtered. The building where he worked was called shlobrik [Editor's note: Ernest explained that the word 'shlobrik' was a dialect word used in Mukachevo area. This word may have came from the merging of the Yiddish words, 'shekht' meaning 'slaughter', and 'rekht' meaning 'right'.] There was one big room where many Jews went on the eve of a holiday. They were standing in lines to the two shochetim. There were many hooks nailed in the counter from the side where the shochet was standing. The owners brought their chickens with their legs tied together. The shochet hung chickens with their heads down on the nails. He had to strictly observe all the rules. He had his knife in his mouth. To slaughter a chicken he instantly cut the poultry's throat. The chicken was still kicking and the blood was splashing around. The shochet took the chicken off the hook and gave it back to the owner. The blood was still flowing from the chicken. It was a terrible sight. Jewish families usually sent children to the shochet. We liked going to the shlobrik before holidays since there were many other children there and we could enjoy talking. Children sometimes brought somebody else's chicken home and mothers had the idea to tie the chicken's legs with colored shreds so that a kid could easily recognize which chicken was his.

In cheder children mainly studied religion. There was also a Jewish grammar school funded by the Zionists. The teachers at this school belonged to various Zionist organizations. Kugel was the last name of the director of this school. He was a handsome tall man. The children studied Ivrit spoken in present-day Israel. There were teachers from Palestine in the grammar school. The Hasidim weren't happy with this grammar school since it didn't focus on religious subjects. This building still exists. It houses the Trade College today.

There was a yeshivah, a Jewish higher educational institution, in Mukachevo. The chief rabbi at the yeshivah was the popular Hasidic rabbi Chaim Spira [Shapira] 9. Our Hesed in Uzhgorod is named after him: Hesed Spira. Spira was a very authoritative Hasid known all over the world. I remember him very well since my father and I went to get shirayem - leftovers. A rabbi traditionally invites Hasidim to dinner on Saturday. The rabbi hands them leftovers of the dishes he had tried. Saraim was supposed to bring blessings to a person. Hasidim grabbed every piece from the rabbi's hands. Sometimes they even fought to get them. I remember when at the age of about five I crawled on all fours to the rabbi's table to get shirayem. My father didn't visit the rabbi every Saturday, but I tried to attend every Saturday. On Saturday morning my father went to the synagogue. When he came home we sat down for dinner and I rushed to the rabbi's house to get to the eshraim on time. Once I got confused and instead of sitting at the table with the rabbi I sat at the table for the poor that couldn't afford a festive dinner on Sabbath. They had cholent, beans stewed with meat. I had a meal, but then one of the Hasidim asked my father rather maliciously whether he was poor to the extent of sending his son to have dinner for the poor provided by the rabbi. My father asked me if this was true and then explained the difference between shirayem and dinner for the poor to me.

There was some competition between two rabbis in Mukachevo. Besides rabbi Spira there was the Belzer rebbe, also a popular Hasidic rabbi. He built a synagogue in Mukachevo and the community members divided into the admirers and opponents between the two rabbis. The synagogues of Spira and Belze were close to each other. I cannot tell what it was like with adults, but we, boys, whose parents attended different synagogues, even threw stones at one another. There were conflicts between the rabbis' office and the Zionists, too. One of the reasons was the Jewish grammar school. The grammar school paid little attention to religious subjects. The rabbis were concerned about such abandonment. There were also differences in convictions. Hasidim didn't think it necessary to move to Palestine. They believed that the Messiah would come to lead all Jews to their ancestors' land of Palestine and that they had to wait for Him where they were, while the Zionists were helping people to move to Palestine. Rabbi Spira often made angry speeches against the Zionists and even cursed them.

There is a well-known Jewish curse: 'to erase one's name so that nobody remembers it'. This curse is said at Purim when they mention Haman's name. Every time the name of Haman is mentioned, everyone boos, hisses, stamps their feet and twirls their graggers. Children start their rattles, adults hit the table with their fists and stamp their feet to blot out Haman's name from history. There's the expression 'blot out' the name or the memory of particular individuals. Rabbi Spira often used this expression when speaking about the Zionists. Sometimes it led to scandalous situations. Occasionally students of grammar school threw eggs at rabbi Spira during his speeches. Now I understand that it was wrong, but it wasn't considered to be so at that time: the rabbi spoke against the Zionists and they acted against the rabbi.

There were numerous Zionist parties in Mukachevo. There was the Mizrachi, an Orthodox Zionist party. At the age of 13 I attended a club in the Mizrachi for a short time. There was a dance club where boys danced with girls. My parents were aware that I went there. I was too shy and my parents wanted me to socialize with other teenagers. My mother even made me a fancy shirt for dancing. I was too shy to dance with girls and gave up dancing. There were other Zionist parties. There was a Zionist party called Betar. I would call them fascists. Those Zionists believed that they could reach their goals with weapons and force. There was the Hashomer Hatzair 10. They were chauvinist Jews, but they were communists. It still exists in Israel, and also has the same name. They are Zionists and speak for the State of Israel, but they believe that this state must be communist, or at least socialist. All Zionist parties were more or less religious and were in opposition to one another. There was an active and interesting life in Mukachevo.

Rabbi Chaim Spira died in 1937. Hasidim from Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Poland came to his funeral. My father took me to his funeral although my mother protested. She was afraid that I might be treaded down by the crowd. I can remember very clearly the funeral of Spira. The whole town was in mourning. There were black cloths on the houses and people wore dark clothes. It looked as though it got dark all of a sudden. Non-Jewish residents also came to the funeral. There were police patrols in the streets and policemen were wearing special safety hats in case of trouble. People took turns to carry the casket from the house where Rabbi Spira lived, across the town and out of town to the Jewish cemetery. Every five to ten meters the casket was handed over to another group of men. There were so many of those that were willing to carry it that the casket could have been easily handed over all the distance between Mukachevo and Uzhgorod. Men were carrying it on their shoulders to pay honor to Rabbi Spira. People were crying. However young I was I remember this overwhelming grief. So many people came to the cemetery that there wasn't an inch of space left there.

My father, Eshye Galpert, was a Hasid and dressed according to the fashion. He wore a long black caftan and a black kippah, and a black hat and a streimel on holidays. He had a big beard and payes. My mother wore a wig and dark gowns. We only spoke Yiddish at home. We, children, spoke fluent Czech and studied in a Czech school, but our parents didn't speak any Czech since they were born in Austria-Hungary. The older generation and my parents, too, spoke Hungarian to their non-Jewish acquaintances.

Our father closed his store in the late afternoon and our neighbors knocked on our window if they needed something in the evening. Sometimes somebody felt ill and his relatives wanted to get a lemon for him at night. My father gave them what they needed through the window. He had to get up at night rather often since we had many neighbors. Most of them were poor Jews and my father didn't earn much from them. They used to buy 250 grams of sugar, or even 60 grams when they wanted to serve tea to unexpected guests. Sugar was expensive and very few customers could afford to buy a whole kilo of sugar. My father had his goods packed in packages for various customers. The shops were to be closed on state holidays and the authorities watched that this rule was strictly followed. Therefore, if my father had a customer on holidays he sent us, children, outside to look out for policemen nearby to avoid a penalty. On Sabbath and Jewish holidays the shop was closed and I cannot imagine what might have made my father sell goods on such days. Our non-Jewish neighbors knew very well there was no way to buy anything on holidays and did their shopping in advance. Twice a week my father rode his bicycle to buy goods for his store from wholesalers. He took back the smaller packages and had the bigger ones delivered to the store.

My father had a nice voice and an ear for music. He sang in a choir when he studied in the yeshivah. Father liked singing and music. Uncle Idl had a gramophone. There was a handle to wind it up to listen to a record. Uncle Idl brought his gramophone when visiting us and then my father listened to music. However, he wanted to hear more. Hasidim weren't allowed to go to the cinema or theater. There were music films with Caruso, Mario Lanza and Chaliapin shown in the cinema theater in our town. [Editor's note: Mario Lanza (1921-1959): born Alfredo Arnold Cocozza, he adopted the stage name Mario Lanza in 1942, he sang opera in the movies; Enrico Caruso (1873- 1921): famous Italian opera singer; Fyodor Ivanovich Chaliapin (1873-1938): one of the greatest Russian singers.] My father went to the cinema and stood by the backdoor where nobody could see him listening to the music. What would other Hasidim have said if they had known about my father's likes! When a known chazzan came to town he performed in the main synagogue, my father and I were sure to go to listen to him. Although we lived at quite a distance from the main synagogue on Friday evening or Saturday we went there to listen to a chazzan. My father sang and was a chazzan of the synagogue that we attended each Sabbath and on Jewish holidays.

At the age of three I went to cheder. All boys went to cheder at the age of three. Classes started at 6.30am and my mother woke me up at 5.30 every day. It was especially hard in winter when it was still dark and cold when I had to go to cheder. The cheder where I studied was a small white-painted room in the house in the yard of the synagogue where the melamed lived. I don't know exactly how much parents paid for their children, but I don't think it was much. In winter each pupil had to bring a wooden log for the stove. The rabbi was very poor and we had to help his wife about the house: we cut and fetched wood. We studied until lunchtime then we had a one-hour break. We ran home to have a quick lunch and ran back to cheder. The rabbi allowed us to play. Most of us came from poor families that couldn't afford to buy their children toys. We played football with a ball that we made from stockings.

We studied the Hebrew alphabet in the 1st grade. In the 2nd grade, at the age of four, we knew the alef-beys and could read prayers. In the 3rd grade when we were five to six years old we studied the Torah. The language was the same as in prayers, only nekudes were added. A different rabbi was our teacher in each grade and they had special training for teaching in their grade. There was a bamboo stick used ever since we were in the 3rd grade. Every Thursday the rabbi examined our knowledge. If a pupil didn't demonstrate a good knowledge the rabbi said, 'Take down your pants'. The pupil had to go down on his knee and the rabbi hit him as many times as he believed the pupil deserved. Every Thursday morning I got up in the morning complaining to my mother about a headache asking her to let me stay at home. My father understood very well why I had a headache since he had studied at cheder in his day, too. My mother asked my father to let me stay at home since she believed I was a weak child. One time doctors suspected I had anemia and my mother felt sorry for me, but my father always insisted that I went to cheder. Well, frankly, when I returned home from cheder I never had a headache to go and play outside!

At the age of six I had to go to elementary school. Jewish children went to Czech elementary schools for boys and girls. We had to study at the elementary school and cheder at the same time. School started at 9 in the morning. I had breakfast and went to cheder at 6.30, as usual. We recited prayers and at 8.30 I went to elementary school. After classes I went home to have lunch and then went back to cheder where we had classes until evening. I returned home late in the evening and did my homework for school. However, the schoolteachers knew that we had a busy curriculum at cheder and didn't give us much to do at home.

When I was to start elementary school my father cut my payes. He didn't want me to be different from other children fearing that they might tease me. Senior boys at cheder had long payes and so did my father and grandfather and I wanted to be like them. I began to cry when he was cutting my payes, but my father said that while I was a child he was to decide on the length of my payes and when I grew up I could decide for myself. When I turned 14 or 15 I secretly cut my payes being shy to wear them. My father reminded me how I had cried when he had cut my payes. I wore a tzitzit. At school I hid it under my shirt, but I never took it off.

We were told different things at cheder and at school and I often got confused about it. Once I came home after a class in natural history with tears in my eyes. I said, 'Our rabbi told us that God made this world in six days, but our teachers at school tell us different. Who do I trust? Our rabbi or our teacher?' Though my father was a Hasid he was a kind and smart man and understood that this was a collapse of my understanding of this world and a catastrophe for me. He said the following, 'You listen to both. What the rabbi says you study for cheder and at school you say what your teacher requests. When you grow up you will find out what's right for yourself.' I had all excellent marks at school and had no problems at cheder. On Saturday I visited my grandfather and he checked what I had learnt at cheder during the week. If he was happy with what he heard he always gave me candy. My grandmother gave me candy unconditionally, though. I visited my grandparents after school sometimes.

Girls attended Beit Yakov schools where they learned to read and write in Hebrew. They had classes that lasted a couple of hours once a week. My sisters didn't attend it because they learned at home with our parents. My mother could read in Hebrew and my father could read and write. Actually, girls were not taught to write. They were supposed to be able to read prayers. They didn't know the language and didn't understand what they were reading. At cheder we were taught to read in Hebrew and translate into Yiddish while the girls didn't know it. However, some Hasidic families taught their daughters to read and translate, but there were only a few. There were prayer books in Hungarian translation.

We studied in elementary school for four years and then had to complete four years in the so-called middle school 11. After finishing this school we could go to a grammar school. My sisters and I finished a middle school.

We observed Sabbath and all Jewish holidays at home. On Friday morning my mother started cooking for Sabbath. She made food for two days since she couldn't do any work on Saturday. She bought challah for Sabbath at the Jewish bakery, and vegetables and dairies at the market. Before Sabbath my father and I went to the synagogue. When we returned my mother lit candles and prayed over them. Dinner was ready. After the common prayer my father said a broche, a blessing over the food, and we sat down to dinner. Then we sang zmires. On Saturday morning my parents went to the synagogue. My father took me with him. After the prayer we returned home and father sat down to read religious books. He often read aloud to my sisters and me. For my sisters to understand he translated from Hebrew into Yiddish. He told us about the history of the Jewish people and retold us stories from the Torah. Then we went to visit my grandparents.

During the month of Adar we prepared for Pesach. My father had many religious books: the complete Talmud, the Tannakh and many others. Once a year before Pesach we had to air the books. We took a ladder to the yard and put special plywood boards on it. Then we put all books on these boards and shuffled all pages. This was the start of the preparations for Pesach. There was a list of activities to be completed every day. My mother cleaned the kitchen and my sisters and I had to do the rooms. We had to remove all breadcrumbs and gave all bread leftovers to our non-Jewish neighbors. On the eve of Pesach we checked that everything had been done right. If we didn't believe that everything was as clean as it should be we did the ritual of bdikat chametz, a symbolic clean up. [Editor's note: This ritual was obligatorily performed before every Pesach.] On the evening before Pesach my mother put a few pieces of bread somewhere behind a wardrobe, under the table or on a shelf. My father checked the house with a candle in his hand to determine whether there was any chametz left. He also had a goose feather and a shovel in his hands. He swept the chametz that he found onto the shovel and continued his search of the house. My mother was supposed to remember the number of pieces she dropped. The chametz that my father found was wrapped into a piece of cloth and a wooden spoon was also put there for some reason. This package was placed where it could be seen to ensure there was no chametz left in the house. On the eve of Pesach all neighbors got together to burn their chametz. Everyone had chametz wrapped in a piece of cloth, a feather and a wooden spoon that they dropped into the fire. Then they prayed. It wasn't allowed to eat bread after that. It was allowed to eat potatoes, but no bread.

Then the kitchen utensils and crockery were replaced with fancy pieces. We only used kosher utensils and crockery at home. There were dishes for meat and dairy products and they were not to be mixed. We also had special utensils and crockery for Pesach. We packed our everyday crockery into a basket and took it to the attic or basement and took the special crockery down. It was stored in the attic and was thoroughly packed. First we took down our utensils. We, children, couldn't wait until our parents unwrapped the glasses. Traditionally every Jew was supposed to drink four glasses of wine during the first seder. There were bigger glasses for our parents and smaller ones for us, children. Everybody had his own glass. We grabbed and kissed this crockery so happy we were to have special crockery in the house! We had fancy glasses for Pesach. The biggest glass was for Elijah, the Prophet 12.

The table was covered with a white tablecloth on the seder. We were in a cheerful mood. There were napkins with quotations from the Torah embroidered on them. They were used to cover the matzah. There was a Jewish bakery in Mukachevo where matzah was made. Before baking matzah the bakery was to be cleaned of chametz, then a rabbi inspected it and gave his permission for baking. Each family ordered as much as it needed and when ready the matzah was delivered to homes in big wicker baskets. The bakery was open for a whole month. The Jewish community provided matzah to poor families, but there was very little of it and those people were always hungry at Pesach since they weren't allowed to eat bread that was their major food. A day before Pesach the most religious Hasidim went to the bakery to make their own matzah since they didn't trust the bakers. Shmire matzot was very expensive. [Editor's note: Matzah shemirah is matzah made from wheat, which has been under observation from the time of reaping or grinding] Everybody bought matzah at Pesach, but based on what they could afford people bought different sorts of matzah. My father wasn't fanatically religious and we bought ordinary matzah. Nowadays there are special appliances to make matzah, but in the past it was made by hand. First they made the dough, rolled it out and put it in the oven within 20 minutes. [Editor's note: In most communities today the whole process from kneading the dough to baking must not exceed 18 minutes.] If it took longer the dough was considered to be sour and was no good for matzah. There were special rollers for making holes into the dough. The dough was made from the wheat that Jews had grown. There were Jewish farmers that grew wheat for making matzah. The grain was milled at special mills owned by Jews. There was no non-Jewish hand to touch the matzah. We weren't a wealthy family and we, children, were always hungry at Pesach. We felt like chewing matzah from morning till night, but there wasn't enough of it.

My mother also made stocks of poultry fat during winter time. We bought geese bred by Jews, took them to the shochet and then flayed it with fat on the skin. Before the process the kitchen was to be cleaned thoroughly to remove any chametz. There wasn't a single breadcrumb to be left on the table, since the cooking of fat wasn't to be made when there was any chametz nearby. There was a special bowl for melting goose fat. Then the fat was stored in a container in the attic. Even the poorest families did their best to have goose fat in store for Pesach.

Ten days before Pesach my mother prepared beetroots for borsch [vegetables soup] in a big bowl. She peeled beetroots, put them in water and at Pesach the beetroots turned into beetroot kvass [a refreshing bread drink made with yeast]. In Subcarpathia they called this dish borsch. Before Pesach my mother sent me to the shochet with the chickens. She made chicken broth and noodles. I still cook noodles at Pesach. I make them myself. I add eggs, water and salt to starch and stir it. Then I fry little flat pancakes in goose fat, roll them and cut them thinly. It makes delicious noodles. My mother also made potato puddings to serve with meat. Pudding could be made from fresh or cooked potatoes. Of course, she also made matzah and egg pudding. My mother also cooked cholent: stewed meat, potatoes and beans. She cooked potatoes for the borsch, cut them into small cubes, added eggs and beetroot kvass. It could be served hot or cold to one's liking. My mother made cakes for each day of the holiday. We, kids, also liked pieces of matzah served with milk. I remember pieces of matzah in my light blue enameled bowl.

We were to drink wine at Pesach. However, my father couldn't drink wine due to his stomach acidity. My mother used to buy figs imported from Israel and made special liqueur for Pesach. She made it in a big jar a month before Pesach right after Purim and all this time nobody was allowed to touch it in order to keep it kosher.

On seder my mother lit the candles. Special prayers, different from the ones to be recited when lighting candles on Sabbath, were said. The men of the family went to pray in the synagogue at that time. When we returned home the table was already covered with a white tablecloth and there was food on it. There were candles lit and it gave a special feeling of holiday. Seder was a family holiday. The word 'seder' means 'order'. There's a strict procedure to be followed at the seder. Participants have to recline: the seats were equipped with cushions, so that the participants could lean on them while eating to imitate freemen and nobility. Only my father reclined on cushions. The master of the house wears white clothes called the kitel. It's only to be worn on the seder and to the synagogue on Yom Kippur [Editor's note: Men are also buried in it].

My father sat at the head of the table and we began the seder. The seder procedures are described in the Haggadah. At the beginning of the seder the younger son asks the four traditional questions [the mah nishtanah]: 'Why is this night different from all other nights? For on all other nights, we eat both bread and matzah, and on this night we eat only matzah? For all other holidays we drink one glass of wine and tonight we drink four glasses? For on all other nights we eat all other herbs; and on this night we eat only bitter herbs? For on all other nights, we eat sitting up or leaning, on this night we all eat leaning?' Since I was the only son I asked these questions that I learned in cheder. We translated this conversation into Yiddish for my sisters to understand it. After answering these questions our father continued, 'We were pharaoh's slaves in Egypt...' singing during the recitation. There were intervals when we were to drink wine. Then father listed all the plagues that God brought upon Egypt, the ten symbolic plagues called makkot in Hebrew. Each time my father named another plague we were to pour a drop of wine onto a saucer.

There was a very interesting part when my father broke the matzah into two pieces, wrapped a bigger piece in a napkin and put it under a cushion. This is called the afikoman that is to be eaten after dinner is over. [Editor' note: Actually it has to be eaten as the last pace, without it one cannot finish the dinner.] After my father put away the afikoman we continued the seder. One of the children was to steal the afikoman and father could only have it back for a ransom fee. Of course, my father only pretended that he didn't see the stealing of the afikoman and it was a ritual.

Once my older sister Olga stole the afikoman and I saw where she put it and stole it from her! I spoiled the holiday for the whole family since we both burst out crying. We were to receive ransom from my father, but who was to receive it? Olga was saying that she had stolen afikoman and I was showing the matzah expecting to get the ransom. My father gave ransom to both of us. I don't remember what Olga received, but I got a thick pocket prayer book. I valued it highly having received it for giving back the afikoman.

The biggest glass of wine in the center of the table was for Elijah. We opened the front door so that he could come into the house. Well, we were concerned about leaving the door open since there were non-Jewish neighbors living nearby, but it was quiet in Mukachevo: non-Jews respected Jewish customs and traditions and were used to them. We, kids, couldn't wait until Elijah came into the house and sipped his wine. We expected to see the wine stir in the glass. Sometimes one of us said, 'I can see it!' Then we sang songs. The following day we had a similar seder sitting at the table and having the ritual repeated as if it hadn't happened the day before. In Israel they observe Pesach for seven days and in the galut they added one day to make sure it was done correctly. [Editor's note: Ernest means that in Israel Pesach lasts only seven days with one seder night, whereas in the Diaspora, the holiday last eight days long and there are two seder nights one after the other.] Then came four chol hamoed days. They are weekdays, but they are still Pesach. It's allowed to work or smoke at chol hamoed. The last two days of Pesach also had strict rules. On the eighth day some families had little matzah balls, matzah kreygelakh, cooked of matzah, eggs and black pepper. This was delicious! In Hasidic families it was considered to be a violation of the rules since matzah for matzah kreygelakh was to be dipped into water and at Pesach matzah wasn't to be mixed with water. Even if a drop of water fell on the matzah it wasn't good enough to be eaten at Pesach since wet matzah got sour and became non-kosher. Nowadays we also make these matzah balls when the family gets together at Pesach.

All holidays were nice in their own way. On Rosh Hashanah, when the shofar was blown we went to the synagogue with the family. On this day my sisters went to the synagogue with mother. In some Hasidic families daughters attended the synagogue regularly, but we weren't that fanatically religious. My sisters were with our mother on the upper floor and I stayed with my father. When we returned home from the synagogue my mother put apples and honey on the table that symbolized a sweet New Year. We dipped the apples into honey and ate them.

On Yom Kippur my father and I prayed in the synagogue for the whole day. My mother also went to the synagogue. We had a big enough dinner the night before since we were supposed to fast the whole day. Before I had my bar mitzvah mother always cooked cookies or honey cake to eat before Yom Kippur. My father took it to the synagogue to treat me while he fasted according to the rules. After I had my bar mitzvah I had to fast as well. Yom Kippur was a hard day since it was to be spent in the synagogue. Each family brought one or two candles. They were big enough to burn for 24 hours. They were lit on the eve of Yom Kippur and were left burning until three stars appeared in the sky the following night. All these candles generated fumes at the synagogue and I can't imagine how people could pray in this stuffy air, but their religious spirits probably helped them. There was a festive dinner at the end of Yom Kippur. Jews usually went to the synagogue located nearest to their homes. We went to the small synagogue in Duchnovich Street. That's the ancient name of the street that has been preserved up until today. Looking at the building one knew at once that it was a synagogue. All architectural traditions were observed. It was well maintained. Each visitor had a special chair with a board for reading the Torah. These chairs were called shtenders [pulpit]. There was a very beautiful aron kodesh, in which the Torah scrolls were stored. According to the laws there was a separate section for women on the second floor. There was a mikveh in Yidishgas in Mukachevo.

There are four days between Yom Kippur and Sukkot to make and decorate the sukkah. After dinner the family went out into the yard to start making the sukkah. Children enjoyed this time much. Poorer Jews made a sukkah from what they had at hand. We had a pre-manufactured sukkah of small boards with hooks. We set it up in one evening. Wealthier families that built their own houses had a balcony with an opening roof consisting of two parts. They had a reel roofing for the sukkah and put reed on top. There were gypsies selling reeds in the town. Some people also had reed mats that they used to make the roofing of their sukkah. Sukkot is in the fall when it often rains. When it rained the sukkah leaked and it made eating inside impossible. More religious people managed to catch a moment to have a meal in their sukkah. It happened occasionally that when the rain was over there were still drops of water falling into the bowl of soup. Wealthier families just unfolded their permanent roof to hide from the rain.

Children enjoyed making decorations for the sukkah. We decorated it like a Christmas tree. We made decorations of color paper and competed in whose decorations were nicer. I was good at making decorations and taught other children to make decorations. Children's mothers and grandmothers came to look at decorations that they had never seen before. We had meals in the sukkah throughout all days of the holiday. We took a table out there, ate and prayed there as required.

Purim was a merry holiday. A day before this holiday the adults gave children rattles and whistles. Our rattles were made of wood and plywood. When the Scroll of Esther was read at the synagogue during Purim the name of Haman was often pronounced and all children in the synagogue did their best to make as much noise as they could. On Purim treats - shelakhmones - were taken to neighbors and acquaintances. Children took trays of sweets from one house to another. My sisters and I also ran around with trays. We also received treats and gifts of small coins. Most important were the Purimshpilen. Children or adults prepared a song, a poem, a dance or a short performance at Purim. When preparing we kept it a secret what we were to perform. Then we formed small groups of two to three boys or a boy and a girl to perform in wealthier families. We were given a few coins or treats for it. My sisters and I also took part in such performances. In one day we collected quite an amount of money. Adults also gave performances at Purim. One man whose name was Chaim disguised himself in women's clothes for a joke. He went out with a boy holding an umbrella for him in any weather, even when the sun was shining. The boy also carried a hat for donations. Chaim carried a violin. People shouted 'Here's Chaim coming!' rushing to the street to welcome him. There was a lot of joking during the meal on Purim.

Each holiday had its symbols. The symbol of Purim was the rattle. On Simchat Torah all children had little flags stuck in an apple. On Chanukkah children played with a spinning top [also called dreidel]. There were four letters, one on each side of the spinning top and each letter was the first letter of a word in Hebrew. The letters stood for the words: 'nes', 'gadol', 'haya, 'po', which means 'a great miracle was here''. Each letter had its price. We played for money since on Chanukkah it's the custom to give money as a gift. This was the only day of the year when Jews were allowed to gamble playing dominoes or cards, but we traditionally played with a spinning top. There's a story behind this custom. When the Romans invaded Judea they didn't allow the Jews to study the Torah and Jews had to do it in secret. Children got together to study the Torah, but when they saw a Roman they pretended to be playing with a spinning top. Since then children have played with spinning tops on Chanukkah. [Editor's note: The origins of this custom are slightly different. During the time of the Maccabees, Jews were imprisoned for studying the Torah. In prison these Jews would gather together to play dreidel. Under the guise of idling away their time, they would engage in Torah discussions.] We made spinning tops from wood. We cut the frame and letters and poured lead inside. We were taught how to make them in cheder. My mother lit one candle more in the chanukkiyah each day.

In 1935 Benes became president of Czechoslovakia. After he was elected he visited Mukachevo. There was a meeting in the yard of the military barracks. All the residents of Mukachevo came to the meeting. Our school was also there and the schoolchildren had flags to greet the president. Benes had the same policy regarding the protection of human rights of Jews that his predecessor Masaryk had.

I turned 13 in 1936. Reb Alter, our teacher of Gemara at cheder, which I attended every afternoon after grammar school, prepared me to bar mitzvah in advance. I had to hold a lecture based on a section from the Torah. I can't remember which section it was. This was called the droshe. I had my bar mitzvah on a Saturday. This was the first time I stood by the Torah in the synagogue and wore my tallit. I recited the prayer that one had to recite when called to the Torah. There was a dinner party in the evening to which our relatives, my father's friends and my friends were invited. I was to read the droshe to them. The guests sat at the table. I remember there was beer and yellow peas cooked with paprika. There were big bowls with peas on the table. The guests ate the peas with their hands and drank beer. I read the droshe and then an older Hasid began asking me questions that I could not answer. I burst into tears and left the room. From behind the door I heard other Hasidim telling him off for spoiling my party. It was very hard for me to return to the room. I cried a little more and then my parents and guests talked me into coming back into the room.

Grandfather Pinchas died in 1936. He was about 65 years old. He was buried according to Jewish traditions in the Jewish cemetery in Mukachevo. My grandmother sat shivah for him. After he died my father's younger brother, Idl, took over the Chevra Kaddisha. I don't remember my grandfather's funeral, but I remember when my grandmother died in 1937. Of course, the family was very sad when she died, but I thought it was natural for older people to die. My grandmother was on the floor in a room. Her body was covered with a black cloth. There was a candle burning by her head. There were women sitting around her with their shoes off. They were crying. My father's older brother, Berl, came to the funeral from Palestine. Berl was good at conducting ceremonies. My father told me that even when Berl was still very young he was invited to be master of ceremony at weddings, and, he could make people laugh! That time Berl came into the yard crying, 'Mama, Mama!' Then all those present started sobbing. I felt fear and probably this was the first time I realized that death was final. Grandmother Laya was buried near my grandfather in the Jewish cemetery in Mukachevo. My father recited the Kaddish over her grave and sat shivah.

A year after my grandmother died my father's brother Idl decided to get married. He consulted a shadkhan that found a girl from Khust [60 km from Uzhgorod] in Subcarpathia for him. Her father, Mr. Katz, was a wealthy Jew. Everybody called him 'Polish' for some reason. He probably did come from Poland. He had several daughters. Since Idl's father had died, my father, his older brother, had to take the responsibility of making all marriage arrangements. The negotiations took place at our home and we, kids, showed much interest in what was going on. We were ordered to stay in the kitchen, but we eavesdropped from behind the door. There were the girl's father, my father and the shadkhan. My father and Katz began to discuss the girl's dowry. My father told the girl's father about the important position his brother had at the Chevra Kaddisha and that he was a decent and God-fearing man. He sounded to be the best and most desirable fiancé ever. Mr. Katz said that his daughter was a real beauty. The shadkhan said that the girl didn't need any dowry since she was like gold herself. It was my understanding that neither my father nor Idl had seen the girl. They negotiated for a long time before they reached an agreement. They agreed that Mr. Katz would put the negotiated amount of money into a bank and give the confirmation documents to Mr. Rot, the respected owner of the stationery factory in Mukachevo. If there was a wedding Mr. Rot was to hand these documents to Idl, if not return them to Mr. Katz. Idl's wedding took place about three months after the negotiations. It was a traditional Jewish wedding. There was a chuppah at home. Our mother and all Jewish neighbors did the cooking. It was a joyful wedding.

I turned 15 in 1938 and had to go to work. I became an apprentice to a mechanic, the Jewish owner of an equipment repair and maintenance shop. I learned to fix bicycles, sewing machines, gramophones and prams. My training was to last for two years. I actually started work a year later, but my master didn't pay me a salary. I did repairs and he received all money. He only gave me small allowances.

In 1938 the Germans occupied Czechoslovakia and gave the former Hungarian territory including Subcarpathia back to Hungarians. [Editor's note: The Germans only occupied the Czech lands, Slovakia became an independent state but that part of it, which was mostly populated by Hungarians, was in fact ceded to Hungary in accordance with the first Vienna Decision of 1938.] There were different moods about this. The Hungarians were happy and the older Jews remembered that there had been no oppression of Jews during the Austro-Hungarian regime and were hoping for the better, while the younger Jewish population believed the Hungarians to be occupants and spoke Czech, which was their demonstration of protest against the occupants. In the course of time it became clear that this was a fascist Hungary and the authorities began to introduce anti-Jewish laws [anti-Jewish laws in Hungary] 13. The Jews were forbidden to own factories, stores or shops. They had to transfer their property to non-Jewish owners or they were to be expropriated by the state. Only very few rich Jews managed to buy out their property while the rest lost their licenses and any chance to provide for their families. My father lost his trade license. My master also lost the license for his shop. In 1940 his shop was closed. My father and I had to look for a job. We went to work at Mr. Rot's stationery factory, which was still operating at the time. I became a mechanic and my father was hired as a worker.

My older sister, Olga, was a success with her studies at school. She finished school with all excellent marks and wanted to go to a grammar school, but my father was against it. There were Jewish classes at the middle school and the school was closed on Saturday while in the grammar school children studied on Saturday. However, when my father lost his license Olga had to go to work. She needed good clothes that my father couldn't afford to buy for her. My father talked to Mr. Rot about hiring Olga to work in his office. My father explained to Mr. Rot that Olga wanted to go to grammar school, but that he didn't have the opportunity to support her. He also said that even from a religious point of view he thought it was wrong for a Jewish girl to go to school along with atheists. My father asked Mr. Rot to give her a chance to learn to work in his office so that later Mr. Rot could decide whether he needed her as an employee. Mr. Rot was religious and agreed with my father that it wasn't proper for a Jewish girl from a good family to study in grammar school. He took Olga to work in his office. His factory had business relationships with paper suppliers in Germany and Bohemia. Olga knew Czech and was responsible for Mr. Rot's correspondence. Mr. Rot also hired teachers of stenography and German that came to our home to teach her. Olga became a secretary. Mr. Rot dictated his letters in Yiddish or Hungarian and Olga translated them into German and Czech. She made good use of her knowledge later on in life.

We grew up less religious than our parents. I met with other workers that were communists and this had its impact on me. Of course, we didn't become atheists, but we were certainly not as close to religion as our parents. My mother was very upset about it while my father was more condescending and forgave me many things. When I was in my teens I didn't want to stay at the synagogue until the end of the prayers. When I was leaving the synagogue to go out with my friends my father only asked me to come home when he did to cause my mother no additional worries. Once my mother got angry with me for some reason and said, 'Well, you will get back to religion when you grow older'. We treated our parents with respect, but that time I lost my temper and replied, 'Only if I lose my mind'. I cannot forgive myself for it. I can imagine how my mother must have felt hearing this from me. I feel so sorry that I didn't ask her forgiveness.

At Mr. Rot's factory I met my future wife, Tilda Akerman. She was called Toby then. Tilda and I were the same age. She came from Mukachevo. She told me that we studied together at elementary school, but I ignored her. Tilda worked at the factory. There were other girls there, too. When something went wrong with the equipment they called me to fix the problem. That's how I met Tilda. We had Jewish friends. Tilda's friend Frieda and my friend Voita worked at the factory. Frieda and Voita were going to get married when World War II was over. Tilda and I also fell in love with one another. We met after work and went for a walk. Tilda visited me at home and I went to see her at her home, too. My parents liked her. If it hadn't been for the war we would have got married, but because of the war we didn't know what was going to happen to us.

Tilda was born to a religious Jewish family. Her father, Aizik Akerman, made and sold wine and her mother, Ghinda Akerman, nee Weiss, was a housewife. There were eight children in their family. Tilda was the seventh child. Her older sister, Margarita, finished the Commercial Academy in Mukachevo. She married her cousin Weiss. They both sympathized with the communists. Margarita's husband moved to the USSR in 1938 and she was planning to follow him, when Subcarpathia became a part of Hungary and Margarita got no chance to leave. She had a son named Alexandr. When Subcarpathia became Hungarian territory Margarita had to support her family. She worked as an attorney and translator and took on any work she could find. We don't have any information about what happened to her husband. Tilda's brother, David, was a winemaker just like his father. Philip and Serena, Tilda's other brother and sister, also finished the Commercial Academy.

Serena sympathized with the communists and took part in the publication of a communist newspaper. She married a communist called Borkanyuk, a deputy from the Communist Party of the Czech parliament. For her parents her marrying a non-Jewish man was a disgrace. Tilda's mother rejected her daughter. Serena's marriage stirred up a wave of indignation among the Jews in Mukachevo. This caused Tilda's father's death in the synagogue in 1937, when he was murdered by some lunatic that hit him with a log on his temple. It was because one of his daughters was married to a non-Jew. Tilda had to go to work and Serena and her husband moved to the USSR.

When the fascists came to power in Hungary Tilda's brother Philip moved to Poland and from there to England. During World War II Philip was in the Czech Corps on the Western front. After World War II he lived in Uzhgorod, where he died in 1987. His brother Aron worked at a glass shop. Hugo was also a worker. Tilda's younger brother, Shmil, studied at school. Except Margarita and Serena all other children in the family were religious.

In early 1941 my father was recruited to Hungarian forced labor in Velikiy Bereznyy district. The so-called Arpad line was under construction there. [The Arpad line was a military defense in the Eastern Carpathians, the construction of which was started in 1940.] This was a labor camp of a kind. Jews were not recruited to the Hungarian army, but they had to serve in work battalions constructing defense lines, barracks and doing other construction work at the front. They had no weapons and often perished during firing. My father worked in the forced labor until 1942 when he was released due to his age.

Jews were having a hard life, particularly when the war with the Soviet Union began in 1941. There were many restrictions. Jews received bread per coupons. The wealthier Jews could buy food at a market while the situation was hard for the poor Jews. In 1943 all Jews were ordered to wear round yellow pieces of cloth on their clothes that were replaced with stars, but at least the Hungarians didn't kill Jews and there were no pogroms.

In 1943 my sister married Nuchim Weingarten, a Jewish man from Mukachevo. Our parents arranged a Jewish wedding for Olga. They had a chuppah at the synagogue and the wedding ceremony was conducted by the rabbi. Olga's husband was recruited into a work battalion and from there he went to the front. We had no information about him at the time.

In April 1944 I was taken to forced labor to Hungary. Tilda and I didn't know what was ahead of us. We agreed that we would keep in touch through my father's sister, who lived in Switzerland. We learned her address by heart: Lugano, Bella Visari, 10. I worked in Budapest and then in other places. We dug trenches and constructed defense lines. We stayed in a big barrack with no heating and got little food that barely kept us alive. My friend Voita and cousin Aron, my mother's sister's son, were in the camp with me. We worked from 6am till it got dark. There was a lunch break in the afternoon. When we got to our barrack in the evening we fell asleep immediately. There were guards in the camp, but it wasn't as bad as a concentration camp in general. We could talk in Hungarian with the local residents that told us about what was happening.

In summer 1944 Jews from Hungarian towns and villages began to be taken to concentration camps. We were aware of it. We also knew that all our relatives living in Mukachevo were taken to a concentration camp, but we had no idea about gas chambers or the extermination of Jews in camps. There were cases when inmates of our camp died from hunger or a disease, but this wasn't a death camp. My cousin Aron heard from locomotive operators that drove trains to Auschwitz that this was a death camp, but we just couldn't believe that people could be taken to gas chambers. We just didn't believe it. Only after the war did we get to know what was happening in Auschwitz and that our relatives perished there and how they perished. Both my father and my mother were taken to the gas chambers right away.

When the Soviet troops came to Hungary in January 1945 we were transferred to the Germans. We were under Hungarian rule, but after the transfer to the Germans we were taken to a German concentration camp in Zachersdorf near the Austrian border. However, it was a work camp, too. We worked in groups of 100 inmates constructing defense lines and anti-tank trenches for the Germans. This was in March when the snow was melting and we worked in knee- deep slush. The soil was damp and we had to throw it onto the surface with spades. It was hard work, but fortunately, it only lasted about two months. There were only six survivors in our group of 100 people.

The Soviet troops came to Austria in late March 1945. I had typhoid and was delirious. There were two-tier plank beds in our barrack. I was on the lower tier. On my last working day we were digging a trench and the Germans were training young boys to shoot nearby. I remember an officer yelling, 'The Russians will be here soon. Just pull yourselves together!' We could hear the cannonade already. I lost track of what was going on around me or how long I was delirious. I remember when my cousin Aron sat on my plank bed and said that the camp was to be evacuated and that we had to escape since they were going to burn down the camp. I was in no condition to walk. I told him to leave me and move on when we heard someone shouting, 'The Russians are here!' These words sort of eliminated any signs of disease from me. The six of us crossed the front line. There were bullets whistling around. We were afraid of being killed by a German or Soviet bullet. Finally we bumped into Soviet communications operators that were laying a telephone cable. They were trying to show us to lie down using gestures, but we kept walking. One of us was wounded on his hand. We covered 16 kilometers. Now, recalling this time, I cannot imagine how we managed to get to Szombathely in Hungary [about 20 km from the Austrian border]. This town was liberated from the fascists.

We were taken to a Soviet camp for prisoners of war from Szombathely in late March 1945. Soviet troops sent all those that were behind the front line to camps for prisoners of war. We came from concentration camps and had no documents and we became prisoners along with the fascists that had tried to exterminate us. We didn't have any documents and they took us for Germans or Hungarian fascists. We wore dirty and torn clothes. All prisoners stayed in a field. There were fascists among us. It was raining and very cold. We didn't know Russian. There were guards with machine guns watching us. We tried to explain ourselves saying we were 'zide, which means 'Jew' in Czech, but it only got worse. The guard thought we were abusing Jews and started talking at us. The only words we understood were, 'I will shoot at you!'

The next morning we stood in lines and marched to the railway station. We arrived in Uzhgorod. Again we were ordered to stand in line and marched somewhere with a guard about every 20 meters from one another. We came to a very narrow street in the center of Uzhgorod. We decided to try to escape when we reached a gate leading to a yard. Be what may, we thought. When we were near the gate we began to run. The guards didn't follow us. We got to an abandoned house where we found some food. We stayed in this house two days. We were eager to go home. We didn't have any information about home. Aron, Voita and I managed to get to Mukachevo. We walked most of the way. Occasionally we got a ride on a horse-driven cart. Farmers gave us food on the way. When we came home there was nobody there.

We didn't know anything about the situation. We took some rest and then decided to go to the Soviet army. We wanted the fascists to pay their price for what they had done. We hoped to liberate our relatives. We went to a registry office to volunteer to the army. When officers there looked at us they said we needed to go to a hospital rather than to the army. I was as thin as a rake and my companions looked no better. The officer that talked to us refused to accept Voita, but Aron and I kept begging him to recruit us. We were sent to a training battalion in Poland. At that time the war was over. So I happened to serve in the army, but not at the front. Subcarpathia belonged to the Soviet Union and I was subject to mandatory military service. I served in Poland for about a year and then I was sent to Khmelnitskiy, Vinnitsa region, Ukraine. I demobilized in 1947.

Tilda and I were destined to meet. She returned to Mukachevo when I was at service. In 1944 Tilda and her family were sent to Auschwitz where younger Jews were sent to work and older Jews and children were exterminated. The Germans needed workforce. Tilda's family perished in Auschwitz. Her older sister Margarita and her son were also there. Margarita had the choice of not going with her son, but she decided to stay with him and they went to the gas chamber together. Tilda's parents and her younger brother, Shmil, also perished in the gas chamber. David and Hugo perished in forced labor and her brother Aron crossed the border of the USSR and perished in the Gulag 14. Tilda, her sister Serena, who was in the USSR during World War II, and her brother Philip were the only survivors in the family. Serena returned to Subcarpathia in 1945. Philip returned to Uzhgorod from England in 1946.

Tilda and her friend Frieda were sent to a work camp in the town of Reichenbach from Auschwitz. My sisters Olga and Toby were there, too. This camp was located near a military plant of radio equipment. The inmates of the camp assembled radio equipment. Tilda and my sisters were in this camp until they were liberated. My sisters told Tilda that my relatives had perished in Auschwitz. After they were liberated from the camp Tilda and her friend Frieda went to Mukachevo.

My sisters didn't return home. Olga didn't have any information about her husband, who was recruited into the army three days after their wedding. Sometimes life offers incredible surprises: Olga met her husband on her way back to Mukachevo via Czechoslovakia. He was captured along with other guys from the work battalion near Oskol, a Ukrainian town. He was taken to a camp for prisoners of war and from there he was sent to the Gulag. At that time Subcarpathia still belonged to Czechoslovakia. When the Czechoslovak army was formed all Czech citizens kept in the Gulag were sent to the army. They were released from the Gulag to serve in the Czech army. Nuchim was recruited to the Czechoslovak army and went as far as Karlovy Vary [about 300 km from our house]. Then he demobilized. He had many awards of honor and received an apartment in gratitude for his service. He kept coming to the railway station every day to meet trains that brought people home from concentration camps hoping to meet someone that could tell him about Olga and our family. He met Olga at the railway station.

My sisters stayed in Czechoslovakia and some time later, in the 1950s, they moved to Israel. My younger sister Yona got married in Israel. Her husband's name was Stein. Olga worked as an accountant until she resigned. Her son Shuah was born in 1947. He deals in informatics and is professor of Tel Aviv University. Yona was a housewife after she got married. She has two daughters: Margalit, born in 1950, and Erit, born in 1953. Yona's daughters are married and have children. I don't remember their family names.

?ilda returned to Mukachevo. I corresponded with Voita. He told Tilda the address of my field mail. When I received a letter from Tilda I can't tell you how happy I was. I replied to her letter and we began to correspond. Tilda sent me her photograph in her next letter. She signed it on the backside, 'To my darling Ari'. I had this photograph with me and now I have it in our family album.

Tilda stayed in Uzhgorod with her sister Serena. She went to work. I demobilized in 1947 and came to Uzhgorod. Tilda worked at the town trade department. When we met I was wearing a faded soldier shirt and soldier boots. Tilda and Serena gave me their coupons to buy clothes since all goods were sold per coupons. I went to work as a mechanic in a small shop. We all lived in Serena's apartment. She shared her furniture and kitchen utensils with us. I didn't have a passport. I only had my military identity card. Tilda and I lived together without discussing the issue of marriage. Her sister was the only relative we had, so what kind of wedding could we be thinking of?

On 30th April 1948 Tilda and I decided to go for a walk. It was a lovely day. By that time I had obtained a passport. We went outside and then one of us said, 'Let's go to the registry office'. Things were simple at that time. There were no best friends or advance applications required. We went to the registry office, showed them our documents and the director of the registry office put down our names and issued us a marriage certificate. It was like any other ordinary day. I bought a bottle of champagne and chocolates and invited the director of the registry office to drink to our happiness. He gave us a few glasses and we opened the bottle of champagne. Then we were photographed in the photo shop in the same building as the registry office. We went outside and Tilda said she had to go to work since her colleagues were going to prepare for the celebrations on 1st May. My colleagues were also going to have a celebration and invited me to come. So we parted and each went to his work. This was our wedding day. Shortly afterwards my friend Voita and Tilda's friend Frieda also got married. They lived in Uzhgorod until the 1970s and we became lifetime friends.

I didn't face any anti-Semitism or prejudices towards me at work. On the contrary, my management began to promote me since I could speak Russian. I learned it in the army. Only few people could understand Russian in Subcarpathia at that time. Later children studied in Russian schools and learned Russian, but at that time I was one of the few that could speak Russian. My friend and I opened a small equipment repair shop. There were many Jewish employees in this shop. Its chairman was Mr. Tamper, a Jew. I earned good money since I was already a skilled mechanic. Once Tamper offered me to go to Kiev where I was to attend a course of training of quality assurance managers. I was the only employee who knew Russian. I talked with Tilda and we decided that it was good for me to go there. I stayed there for a month and finished this course with excellent results.

When I returned home it turned out that the chairman liquidated the shop where I was working. He had the intention of appointing me to the position of manager of the metal-ware shop. The manager's salary was much lower than what I had received previously, but I had no choice since the shop where I had worked was closed. This shop was converted into the Bolshevik Plant where I was the manager of a shop. I did my work well and began to implement modifications. I liked new developments and I also received bonuses for them that compensated my loss of salary. The management appreciated my performance and began to talk to me about going to study in a college. To enter a college I had to finish secondary school. Neither Tilda nor I had a secondary education. She and I decided to go to an extramural secondary school.

Our son Pyotr was born in 1951. His Jewish name was Pinchas after my paternal grandfather. Our second son, Yuri, was born in 1955 and has the Jewish name of Eshye after my father.

We hired a babysitter for Pyotr to be able to attend school. My wife and I studied in a Sunday school. We had classes the whole day on Sunday and had homework to do on weekdays. We finished this school and obtained secondary education certificates. Now we could continue our studies. I finished the extramural department of the Machine Building Faculty of Odessa Machine Building College and defended my diploma thesis with honors. The plant kept expanding. When I started work there were about 30 employees in my shop, but when I finished college there were already 80 employees. I became technical manager of the plant. I was content with this position. I wasn't a career-oriented man and was content with what I had.

When I was appointed as technical manager the management convinced me to join the Communist Party telling me that it would help me to make a career. Only members of the Party could have key positions in the former USSR. I obtained recommendations and was to be approved by the bureau of the town party committee. Everybody knew that I had the reputation of a skilled engineer and there were no objections to my membership in the Party.