Genrikh Yakovlevich Len

Russia

St. Petersburg

Interviewer: Lyudmila Lyuban

Date of interview: February 2002

Genrikh Yakovlevich Len is a man above average height, of stout constitution and gray-haired, but he looks rather young.

By character he is very active, persevering, speaks loudly, and you can feel that he is used to achieving positive results in every situation. His words are convincing;

it is clear that he was a professional teacher and lecturer.

He still delivers lectures on Yiddishkeit and other issues at Hesed 1 as a volunteer. In spite of the fact that Genrikh Yakovlevich is retired now, he remains a busy person,

and it’s hard to make an appointment with him, you have to postpone the meeting several times.

However, he is always friendly, responsible and tries to keep his obligations.

My family background

I, Genrikh Yakovlevich Len, was born in 1938 in Leningrad [today St. Petersburg]. My ancestors on my father’s side came from Poland. My grandfather on my father’s side, who was called Naum Yakovlevich Len in the Russian way 2, had the original name Chaim Nukhem Len. He was born in Poland, in the small Jewish town of Vogyn in Radzynsky district in 1888. He was from a well-to-do family. In 1916, during World War I, he took his wife, my grandmother, and their two sons – Yakov, born in 1910, and Samuel, born in 1915 – and left for Russia. As far as I know from the stories of my relatives, he wanted to reach America and settle down there, but the war was going on in Europe, and he remained in Russia.

In 1920 he lived in Samara, where his daughter Maria was born. [Editor’s note: Samara (named Kuibyshev between 1935 and 1991) was founded in 1586 as a fortress. A major center of cereal trade in the 19th century, as well as lard, wool and leather. From 1851 the center of Samara province. Some monuments of civil architecture of the late 19th/early 20th century are well preserved until today.] During the period of the NEP 3 he became a nepman, a dealer, he had enough money, owned a business and their house was very well furnished, as I was told. The children were taught languages and music.

All that came to an end when the NEP was abolished. Grandfather was sent to a labor camp 4 for ‘reeducation’ because he was a nepman: to fell trees in Perm district. Grandmother formally divorced him, as was customary then, and moved to Leningrad with the children in 1929. Having come back from timber cutting, Grandfather worked at the shoe factory ‘Skorokhod’ as a cutter. He was of a very robust constitution and strong physically; he also had, as they say, a Slavic appearance: light eyes, fair hair, 185 centimeters tall. His considerable physical strength allowed him to be a cutter of footwear.

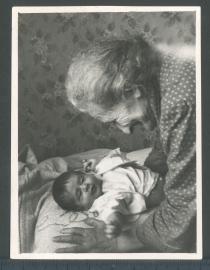

Grandfather’s native language was Yiddish; he didn’t speak Russian very well and had a pronounced Jewish accent. When people met him in the street, they often thought he was a spy with a bad command of Russian. He was quite religious, but not a conformist. I was subjected to the customary circumcision in 1938. You can understand how Jewish traditions were observed in the family even in those hard years 5. Granddad received religious education in his birthplace in Poland. He knew very well the history of his people, traditions of the Jewish nation and observed them. I was small and can’t remember more details.

I remember how Grandfather used to give me a ride on sledges, when I was three years old. He loved his grandchildren very much. He was very devoted to us. His deprivation of civil rights, which was announced to him as a nepman, didn’t knock him out in any way; he continued to believe in the good future for all his family. In Leningrad Grandfather had two rooms in a communal apartment 6 in Zagorodny Avenue, where he lived with his wife and children, of which my father was the elder. Grandfather lived in Leningrad until 1942, stayed here during the blockade 7 and died of famine in January 1942. He was buried in the mass grave in the Piskarevsky memorial cemetery.

My grandfather’s brother continued to live in Poland; he was a merchant, quite a prominent businessman. His name was Genokh, the Russian equivalent would be Genrikh. Therefore I was named, as I heard from my relatives, in his honor. Genrikh was a trader, an owner of extensive property. He had a stone house, a big courtyard. He got stuck in Poland during the German occupation, almost got through it, but in 1945 was killed by the Germans or by local inhabitants, presumably in Lodz [today Poland]. During the Holocaust he was a worker, at the disposal of the local commandant. Probably, being rich, he regularly paid off the Germans, for them to leave him alive, and they, as the Russians say, gradually ‘milked’ him, until they picked up all he had, and then they did away with him. No one of his family survived in Poland, and all the property was lost. Both brothers perished being comparatively young, neither one had lived up to the age of 60.

My grandmother on my father’s side was in the Russian way called Eugenia Lvovna Len after her marriage. Upon birth she was named Gitsa Litmanovna Skurnik. She was born in Poland, too, in the same small town where Grandfather was born, in 1891. At 18 she was already married. Being the most beautiful girl in town, she married a rich man. Grandma Eugenia Lvovna was a seamstress and a housewife. They moved to Russia, as I already said, in 1916, and they first resided in Samara, and then in Leningrad.

My grandmother received her education in a cheder in her native town. She was not particularly religious, and after the death of Grandfather she practically didn’t observe any traditions, but celebrated Jewish holidays. Grandmother didn’t observe the kashrut. Her native language was Yiddish; she spoke poor Russian with a Jewish accent.

During the Holocaust Grandmother lived in Leningrad, in the blockade, and in 1943, after the blockade was lifted she was evacuated to Kuibyshev [formerly Samara], from where she returned to Leningrad in 1946. When her daughter Maria got married, Grandmother moved to live with her in Moscow. She died in 1964 in Moscow in her daughter’s family, and was buried at the Jewish Vostryakovsky cemetery.

Her brother, Khenik Skurnik, also born in Poland, in 1901, went to serve in the voluntary Polish army, participated in the revolutionary movement, was an active member of the Communist party of Poland from 1919 to 1923, carried out revolutionary work among poor and landless peasants of Rodzynya, Narchev, Lukov. He was repeatedly arrested, was many times behind bars, persecuted by the police and was compelled to move to Warsaw in 1921, where he was a member of the Communist organization of the dressmakers’ trade union until 1923. In 1923, due to the risk of another arrest, he was sanctioned by the Central Committee of the Communist party of Poland to escape to the USSR. There he wanted to serve in the Red Army, but they didn’t allow him, as he was not a USSR citizen. He became a citizen and consequently a soldier of the Red Army.

By the end of the Civil War 8 he found himself somewhere in Turkestan [old-fashioned designation for Central Asia]. Once they received an order to send one of the soldiers – a party member – to Leningrad, to get a legal education. It was necessary to train judges for the Soviet Republic. Khenik, as I was told, asked the commander of the battalion, ‘Why me, of all the guys?’ And the commander answered, ‘You are the only one in the entire battalion, who did not ask me to write addresses on your letters, you did it yourself, which means you’re literate, therefore you are going to go and study.’ He was admitted as a student of the Leningrad university, as a military man directed by the Communist party. He lived in a hostel, and by the time of his graduation his nephew came to join him – my father. Other relatives followed his example very soon.

After obtaining legal education, Khenik served as a people’s judge between 1935 and 1937. He frequently acted as a judge in court cases of Poles and Jews, thanks to his good command of both Polish and Yiddish. At the end of 1937 he was subjected to repressions 9, announced an ‘enemy of the people’ 10 and put in jail for ten years. His wife, having learned about it, hanged herself.

Grandmother Eugenia Lvovna first took care of their small son, born in 1936. Later she sent the boy to an orphanage in the town of Pushkin in Leningrad region, because she was afraid that the boy would be taken away from her as ‘the son of an enemy of the people.’ In 1941 the child was evacuated with the orphanage to the Urals.

Khenik served his term in prisoners’ camps, survived, and was released in 1947 without the right of residing in Moscow and Leningrad. He took his son and went to Western Ukraine, to live closer to his native land. However, in 1956 he was rehabilitated 11 and restored in the Communist party. By then he already was a veteran of the Communist party with huge experience, but he flatly refused to work as a people’s judge any more. His son first studied in a military school in Kiev [today Ukraine], then in Odessa [today Ukraine], and finished his service in Minsk [today Belarus] in the rank of lieutenant colonel. Khenik died in 1990 in the family of his son in Minsk. Most of the truthful family stories were recounted to me by him.

According to my Uncle Khenrik Skurnik, there were both poor and rich Jews in the small Jewish town of Vogyn in Poland, where all my ancestors on my father’s side lived. There were handicraftsmen, military officers, dealers, and, of course, everybody lived very different lives.

By the way, the surname Len originates from a nickname, because the square of land in Western Europe was measured in lens. One len was not less than half a hectare, it was not the 0.06 of a hectare that is usually owned by kitchen gardeners 12 in today’s Russia. Some people had up to 100 lens. But even a man, who possessed one len, for which my ancestors received their surname, was already considered a land owner, and had the right to shout at meetings: ‘Off with the king!’ These small landowners were authorized to serve in the Polish army, if they wished, and could pursue a military career.

It is known that my distant relatives served as high-ranking military officers in the 1800s, and this military inclination periodically manifests itself in our kin. The Lens belonged to merchants of nothing less than the second guild 13 and were rich enough and quite independent in that small town. The Skurniks were by origin more noble, but impoverished. Therefore the Skurniks took to revolutionary activity, and the Lens stayed in trade.

My ancestors on my mother’s side came from Belarus. My maternal grandfather, Abram [Avraam] Mendelevich Sorkin, was born in the small Jewish town of Drutsk, Tolochin district, Belarus, in 1885. Later he moved to the town of Tolochin with his family. He was a handicraftsman by profession. His last job was that of a storekeeper in the artel 14 ‘The Red Fuller.’ He was religious, observed all Jewish traditions. His native language was Yiddish. He couldn’t write Russian. He didn’t serve in the army because of his poor health and as the single son of his mother Perl, my great-grandmother.

Perl Sorokina was born in Belarus in 1850, was a housewife, had a poor health, but a strong character. Grandfather Abram remained single for quite a long time until his mother allowed him to get married. His wife, my grandmother Golda, recollected that they hadn’t left for America in the 1920s, when all their close relatives were leaving, because her husband couldn’t oppose his mother Perl, who categorically objected to his departure. The moment for emigration was quite convenient because their children were still young and didn’t have their own families. However, Abram, as an obedient Jewish son, followed his mother’s advice. Great-grandmother Perl lived up to a very old age and died in 1936, after the arrest of her son, my grandfather. He perished in 1937 upon false denunciation.

He was arrested in the town of Tolochin. He was put in prison in that town, and there his track is lost, and we don’t know where exactly he was executed. In 1956 he was posthumously rehabilitated after my personal inquiry. I have an official confirmation, that he was relieved of all accusations. As to the place of his death, specified in the reference sent to me, everyone understands that it is very approximate. The fact that Abram Sorokin was posthumously rehabilitated due to the absence of corpus delicti, became known to me from the letter signed by the General Public Prosecutor of the Belarusian Republic, because the case had been reconsidered there. As it was required to issue a pension to his wife, my grandmother Golda, due to the loss of all support, I requested the certificate of Grandfather’s death, and it was sent to me. And they also advised me to obtain a reference from his artel, stating how big his salary was. Relatives of the deceased, that is my grandmother, had to be compensated in the amount of his two-month salary. I asked Grandma, what the name of that artel was before the war, in what street it was located, and who the neighbors were. And she mentioned one man, who used to live in the neighboring house and work with Granddad. I wrote a letter to that man with this request: ‘Due to rehabilitation of my grandfather would you be so kind as to inform me of any facts that you know about his life?’

In response I received several letters from that man, who was arrested together with my grandfather and very badly beaten on the very first night, then sent to a settlement in Kazakhstan, survived, returned and was rehabilitated after some time. He wrote that the situation in prison, beatings, shouting, groans and all the rest was obviously so terrible, that apparently Grandfather was beaten to death during an interrogation on the first night. Otherwise he would have got to the same settlement, because he was not really guilty, all members of the artel were arrested on accusations of financial deficit and putting the artel on fire to hide those shortages, which apparently they didn’t do.

In the official death certificate it was stated that Grandfather died in 1942 in some village in the Urals. Grandma, having read the certificate, burst into tears and said, ‘I wonder how he could hold out for five more years in the camp with his poor health.’ The letters of the witness leave an eerie impression, no one would ever want to re-read them, because it is a ghostly and detailed story about all the hardships suffered by the prisoners. My sister keeps those letters. I don’t have them. But many people faced the same dreadful destiny in those times.

My grandmother’s name was Golda Yankelevna Sorkinа, nee Kagan. She was born in Belarus in the small town of Krupki of Tolochin district in 1885. It was a large Jewish family with seven or eight children. She received religious education in this town, finished a cheder, and considered Yiddish her native language. She could read and write Yiddish, also knew Belarusian and, living in Russia afterwards, studied Russian as well, so she could read newspapers and write letters. She loved to read all her life and respected educated people.

Grandmother lived with her parents for quite a long time. She got married rather late, and gave birth to her first child, my mother Tsiva, in 1912, that is at 27 years of age; then there were two more children, who died in infancy, and son Alexander or Alter was born in 1920. My grandmother kept the house, brought up the children and helped the family of her brother Girsha, who died in 1912.

Her native Jewish shtetl of Krupki consisted mainly of small wooden houses. They were occupied by poor people, generally referred to as ‘ragged.’ But there were also people who had a cow, a goat, a piece of land, a large garden and a good house and who were engaged in the carrier’s trade. Everything depended on physical abilities and presence of the minimum initial capital. The rabbi was certainly in charge of the religious issues, there was a synagogue, it was obligatory to go to cheder, all Jewish traditions were observed.

Children, in spite of living in a small town, received good education, allowing them to continue their education in the future. They read, wrote, counted well and were smart enough to advance in their further careers. Boys could enter a yeshivah. There was also a school for girls who wanted to continue studying after cheder. Of course I can’t remember now what it was called, but I saw in the documents of one of my aunts, that she had graduated from some Jewish school, where they were taught needlework, languages, and were basically prepared for the family life. They studied, first, their native language, i.e. Yiddish, and secondly, it was obligatory to learn the Belarusian language, plus you could optionally master Polish or Russian. Hebrew was not in great demand then.

Originally Grandmother and Grandfather lived in Drutsk, but by 1920 they moved to the town of Tolochin. Tsiva, my mother, was born in Drutsk, and her brother Alexander was born in Tolochin. It was a Jewish town, too. In Tolochin Grandmother and Grandfather had a large house, and according to the jocular memoirs of Grandma, she and her husband had separate bedrooms, and he ‘came whenever he felt like it.’ There was a fruit garden, a kitchen garden, an ice cellar, they kept a cow and poultry.

When the NEP was established, she was smart enough to understand that she could as well make ice cream out of milk rather than sour cream, and sell it. Ice cream was bought like hot cakes. So with her own hands she brought the wealth of her family to the point where it almost equaled the fortune of the landowner Gorzhelovsky, who lived in a nearby estate before the revolution. Grandmother’s means sufficed to send, when it became necessary, both her son Alexander and her daughter Tsiva to study in Leningrad. To spare them from living in hostels, each one had been bought a separate room.

Soon after her husband’s death Grandmother joined her daughter in Leningrad bringing all her belongings with her thanks to the help of her son who worked at the railway. She brought everything from her native town: home utensils, candlesticks, all those home appliances that are still kept in my house. She took a part of the kosher dishes, special wine glasses for Pesach celebrations, as well as other things that were not so valuable, but that are now considered antiques, and cannot be taken out of Russia. Grandmother also brought her books that accompanied her through evacuation and war. I have handed over a part of these books to the synagogue, and I still keep some, which, unfortunately, I can’t read.

They include the following books: first, prayer books, because Grandmother knew exactly which chapter should be read each Saturday, and she read them not just formally, but with deep understanding; secondly, there were the stories by Sholem Aleichem 15, and there were some short historical books issued in imperial Russia, by a printing house in Vilno [today Vilnius, Lithuania]. I remember checking where it was all published, and of course the nearest cultural place to where they lived was Vilno.

Actually my relatives lived within the territories allowed for the residence of Jews 16, and I don’t think they ever travelled farther than Orsha. And only cancellation of residence regulations and the increase of my grandmother’s wealth allowed her children to go and study in Leningrad. It is understood that some preferred to stay in Tolochin, and the town suited them well, because there was a beautiful river, remarkable gardens, the weather was always fine and the natural conditions very good. It was a very warm place and very attractive to summer residents.

When the war 17 began, Grandmother was evacuated together with our family to Kuibyshev, and we returned to Leningrad in 1946.

The destiny of her elder brothers and sisters is almost unknown to me, except that some of them, including her brother Meyer and sister Elke had left for the USA in 1920, when it was still allowed, and Grandmother helped them with money; but then their traces were lost. I only heard from some relatives, that Vulf, the nephew of Grandmother Golda, the son of one of her sisters who left, married a German lady and lived in Germany, and they had a son. Vulf was rich and had a factory. When in 1930 Russia was struck by famine 18, he sent a letter to his relatives here welcoming them to come and live with him in Germany. When Fascists came to power in Germany, he was executed, as were both his German wife and his son. All their property was confiscated by the Gestapo.

About the lives of other relatives, who stayed in Russia, I know the following. When Grandmother’s elder brother Girsh died in 1912, there remained a mill and flour-grinding manufacturing facility. The widow of this brother was not a businesswoman by character and only spent her time with her three children, and Golda, very reasonable and vigorous, operated the mill. She put all her effort in management during several years and then handed everything over to the family of her brother, for which she was deeply respected by all her relatives.

Her brother’s daughters subsequently got married and lived in Leningrad. Tsilya’s husband was a militiaman, Nata’s a technologist with the Leningrad metal factory, and Dora married a watchmaker. As it happens in Jewish families, Dora’s daughter Sophia, born in 1926, married Uncle Samuel, my father’s brother.

Grandmother’s sister Maryasya moved to the town of Shuvalovo, Leningrad region, in 1929. Maryasya’s husband, bearing the surname Solovei, was a butcher, providing kosher meat for the Leningrad synagogue. They were well to do and owned a large house. Their daughter Rosa [1920-2002] was a housewife, and her son is a businessman now, involved in trade and living somewhere in Shuvalovo.

My father, Yakov Naumovich Len, was born in the small town of Vogyn of Radzynsky district, Poland, in 1910. In the Polish documents he was registered as Yankel Itskhak Len. He moved to Russia with his parents as a child in 1916 and lived at first in Samara and then in Leningrad. His family supported his aspiration to acquire an education. He entered the Philosophy Faculty of the Leningrad State University in 1934. Before university he was a fitter, worked for two or three years as a manual laborer. When he was a third-year student, the Philosophy Faculty was liquidated for ‘sedition’ [anti-Communist dissident activity]. Students were offered to shift to the third year of the History Faculty, or to the first year of the Physics Department. Father chose the latter, which was why it took him so long to complete his studies – seven years. During his training he taught Physics in an evening school.

My mother, Tsiva Abramovna Sorkinа, Len after marriage, was born in the small town of Drutsk in Tolochin district in Belarus in 1912. She went to study in Leningrad approximately in 1930. She studied in the Institute of Silicate Technologies. Grandma had bought a room for her; it was possible then, because there was a lot of uninhabited living space that year. Sorting out her registration documents in the passport bureau, Tsiva met her future spouse Yakov, because, as it turned out, they lived very near from one another. It was in 1933, when Father was 23.

My father married my mother at the end of 1934, graduated from the university in June 1941, having received a diploma of a Physicist – a rare diploma for that time. By then he already had two children: my sister Polina and me. It seems that they didn’t receive their parents’ consent for marriage at once, because both were students, but obtained it after all. According to their ‘Certificate of Shlyuby’ [certificate of marriage in Belarusian], it happened in the town of Tolochin in 1934. ‘Shlyuby’ means ‘love’ in Belarusian.

I think that the wedding took place at the house of my mom’s parents, the Sorkins, who had a big house, with a large garden; they kept a cow and there was enough milk, butter and sour cream. There was a large apple garden. I was born in 1938 and I actually spent half a year in the summertime at Grandmother Golda’s place, as my parents continued to study in Leningrad. In 1940 my younger sister Polina was born. In order to help her daughter, who had to work after graduation from the institute 19 – Father was still a university student – Grandmother Golda finally moved to Leningrad. By that time her husband had died. She sold the house reserving the right to come and stay there each summer.

I have a sister, Polina Len, after marriage – Ezrokh. She finished the Shipbuilding Institute in Leningrad, worked as an instrument engineer in the Research Institute Hydropribor [institute developing devices for ships]. She retired in 1995 and has lived in the USA, in New York City, since 1998. She has two children: son Alexander, born in 1963, who lives in New York at present and works as a programmer. Another son Eduard, born in 1970 remained in St. Petersburg, Russia, and is an engineer. She has already got three grandchildren.

My father’s brother, Samuel Naumovich Len, was also born in the small town of Vogyn in 1915, was taken to Russia as a baby, lived in Samara, and from 1929 in Leningrad. He was a sportsman, got enlisted in the Soviet Army as a volunteer and fought in the Great Patriotic War, was awarded with an Order of Glory, numerous medals and after the war graduated from the evening course of the Machine-Building Institute at the Leningrad metal factory, where he worked in the department of the chief technologist. He married Sophia, who was my second cousin. Sophia was a pharmacist by profession. They had two children: a daughter and a son. They all together left Russia for the USA in 1981. Samuel immigrated to the USA in his pension age and died there in 1996. He is buried in New York.

My father’s sister, Maria Naumovna, was born in Samara in 1920, moved to Leningrad with her relatives, and after leaving school entered the Medical Institute. During the blockade she was a doctor in a hospital. It was a military hospital in Leningrad. Students were granted doctors’ degrees ahead of time. After the death of her father in 1942 and after the breakthrough of the blockade, she went to Kuibyshev. She graduated from the Medical Institute there. All of us were moving between these two poles: Samara [Kuibyshev] and Leningrad.

In Kuibyshev, having completed her medical education, Maria received her first assignment – a camp doctor for Soviet citizens subjected to repressions after the war. There she obtained a vast experience. She told me how she used to wander around the camp with her friend making out from how a prisoner looked which clause of the criminal code he had been convicted for and for how many years. Then, having the right to look into the personal files, they verified their guesses finding out what experts they had become in such issues. She didn’t work there for long.

She married Isaak Vaiman and went to live with her husband in Moscow. Her son was born there, and she took her mother to Moscow later. She lived in Moscow before her son left for Israel. After the deaths of her mother and husband she left for Israel, where she has lived since 1979.

When Mom finished the institute, she worked as a technology engineer at the brick factory #1, and then in the Transportation Research Institute until 1941. Mom was not religious. Her native language was Yiddish, but she learned to speak Russian without any accent.

During the war

After the war began, in August 1941, we went to Kuibyshev, where Father was assigned a job as quality control engineer of planes at a military plant. He was working by methods of non-destructive tests. After Mom’s death in 1942 Father became a widower at the age of 32, with two small children and a mother-in-law to support. We returned to Leningrad in 1946. Father started to live with his mother, my Grandma Eugenia. The living space belonging to my mother and us had been lost in the war perturbations. Father got married two more times. He worked in his field of specialization, in the Research-and-Production Association ‘Positron’ in Leningrad, but he was barred from defending his candidate’s thesis 20 as a Jew. He was not religious, knew some Yiddish, but spoke and wrote Russian in everyday life; he did not serve in the army. He died in Leningrad in 1972.

As I mentioned before, when the war began, we were evacuated to Kuibyshev where Father worked and Mother got a job in a drugstore. We were given a very bad living space in the district called Bezymyanka [‘nameless’ – in Russian]. I was attending a kindergarten there. We lived in one room with Grandmother Golda, all together.

My grandmother Golda lost her son Alexander in 1941, and in 1942 her daughter Tsilya, my mother, died. Grandmother was a woman with a strong character, she was terribly upset, mourning the deaths of her closest people and unable to understand what God had sent her such severe trials for – the deaths of her husband, son and daughter – but she never lost her spirit. She had her grandchildren to take care of, and she managed to bring them all up.

After the war

Grandmother lost her room from the pre-war times in Leningrad, so she first lived in the house of her niece Dora and then moved to the settlement of Vsevolozhskoye in Leningrad region together with her grandchildren, where they rented a house. At the age of 60 to 65 she worked as a seamstress at home. Pension was granted to her much later, when she turned 70, after the rehabilitation of her husband. She was tall and strong, and at the age of 70 chopped firewood herself and brought water from the well. Grandmother was a clever and fair person and all our relatives always listened to her opinion.

Living with Grandmother Golda in Vsevolozhskoye, I brought her matzot from the synagogue on Pesach, lit candles for her on Sabbath, so I could see her performing all the religious customs, but still we didn’t have a very strict religious atmosphere at home. Grandmother observed the kashrut. She was a strong-willed woman. When at the age of 75 she had to go to hospital with a cataract, people were asking her, ‘How are you going to live there, what are you going to eat, there is no kosher food there?’ and she answered, ‘No problem, I’ll eat whatever they give me.’ And she lived ten more years after that.

From Grandmother Golda I learned a little bit of Yiddish, so I can understand the language and I know some Jewish traditions from her stories. She died in Leningrad in 1970 in the family of her granddaughter Polina. The burial service was in keeping with Jewish tradition in the Small Synagogue, which was situated in the Preobrazhenskoye Jewish cemetery. She is buried in the Jewish section 21 in the ‘Cemetery of Victims of the 9th of January’, in which two plots – numbers 62 and 64 – were specially allocated as burial places for Jews. I remember how I took the rabbi back to the synagogue after he had completed the prayers.

Golda had a son, Alexander Sorkin, born in 1920 in Tolochin. He also left for Leningrad to study in the Railway Technical School, served in railway troops, and never married. It so happened that in 1941 he got killed on the territory of Kazakhstan not far from the railway station Timertau during the construction of the railway Timertau–Karaganda, built by convicts. The documents we have state that he fell victim to a gangster attack. It could have had something to do with his nationality, or with his uniform, because the black railway uniform was very similar to the one of security guards. There were many gangsters at railroad construction sites then. Alexander had rather a hot temperament and probably just came across some of the bandits. It happened in November 1941.

As I mentioned earlier, we returned to Leningrad in 1946. Father got married for the second time, and we had a stepmother. I was not on very good terms with my stepmother, so my sister Polina stayed with Daddy, and I moved to live with Grandmother Eugenia. We lived for several years in Zagorodny Avenue; it was a large communal apartment consisting of 12 rooms, where Jews and Russians coexisted, sometimes in peace and sometimes at enmity. By the way, such a well-known man as Nechiporenko, people’s actor, had also lived in that apartment for some time, with his daughter, with whom we were friends. The apartment is shared until today.

Later Grandmother Eugenia left to live in Moscow with her daughter who had her own family, and Father got married for the third time. Then our family rented a house in the town of Vsevolozhskoye, where Grandmother Golda settled with us. Polina and I went to school there, and Father used to give us money. We lived there from 1950 to 1961. In 1961 we received two rooms in Leningrad, as people who lost their accommodation during the war. Grandmother Golda and Polina moved to one of the rooms in Troitskoye Pole, and I moved to the second room in the city center.

From 1952 to 1956 I was a student of the Technical School of Communications in Leningrad specializing in ‘governmental communication.’ I was only 18 years old, and according to legislation of those times I had to wait until I turned 19 in order to enter a higher educational institution. I worked at a factory for one year, and then, due to excellent graduation marks from the technical school I was to be admitted to the Military Academy of Communications. But in 1957 the leader of our state, Nikita Khrushchev 22 announced the reduction of the armed forces, and plenty of reservists were written off, and all the first-year students of the Academy were transferred to the Leningrad Electro-Technical Institute of Communications named after Bonch-Bruevich, and to other educational institutions as well.

So from 1957 to 1963 I studied and graduated from the Institute of Communications, evening department. I combined my studies with working at the factory ‘Mezon’ as a technician. After graduation from the institute I received the specialty ‘engineer/ officer of communications’, and started to work in the same institute as an engineer, later entering a post-graduate course.

After completing the post-graduate course in 1971, I encountered a serious problem of anti-Semitism. I became a candidate of engineering science then, but had not received an assignment for work. Such assignments were given to all post-graduate students who had defended their thesis at the same time with me, except for three persons – all Jews, and I was among them. We received the so-called ‘free employment,’ that is, we were supposed to find work ourselves, and it was not an easy task for Jews in those times.

At first I worked as a non-staff teacher in the institute, but then I was compelled to shift to the research-and-production association ‘Thermoinstrument,’ where I worked in the position of chief quality control engineer from 1973. But that work did not suit me, and in 1977 I changed jobs and worked as head of the design bureau in the ‘Sputnik’ factory. From 1981 to 1989 I occupied the post of senior scientific employee in the institute ‘Lengiprokhim’ [research and design institute of chemical industry]. They still didn’t allow me to be staff professor in the Institute of Communications, and from 1990 to 1997 I taught in the technical school of communications. Now I am a pensioner. In 2000 I received the rank ‘Honorary Radio Operator.’

My personal life

My personal life was not traditional for a Jew. I was married more than once, which is usually unacceptable in Jewish families. My first wife, Inna Mikhailovna Ablavskaya, was Jewish. I met her in the Institute of Communications. She was born in 1940. We had a son. But our family life didn’t shape up properly, our relations became absolutely unsatisfactory. I divorced her long ago. It was, probably, in 1970, when we finally parted. And, being a Jewish wife, she complained about me being in the Party Committee at work, which doesn’t add credit to her personality either. But the Party Committee took my side. In 1987 she left for the USA, taking with her our son, with whom I am on good terms until today: we call and write to each other. His name is Vitaly. He was born in 1968.

Since my position at work demanded that I have a family, I married Tatyana Anatolievna Pomazanskaya two years later, taking a considerable share of risk. She was born in 1946, and seemed to me to be Jewish at first. She worked as a teacher. We officially registered our marriage. In 1973 my second son Anatoly was born. He lives in St. Petersburg now. Tatyana turned out to be Russian. There was much confusion with that. I was mistaken, my father was mistaken, we both believed that she had Jewish roots, but her relatives insisted that they were all Russian. When the mass emigration of Soviet Jews began, she declared, that she hadn’t intended to marry a foreigner, that she was not going to leave for Israel, if I decided to move there. She addressed the director of her school asking not to dismiss her from work [as was customary then], if it became clear that her husband had emigrated to Israel, and that she would rather break off her marriage, and that she had nothing in common with me. Notwithstanding all the fuss, I remained on good terms with Anatoly.

Now I am married for the third time. My wife, Eleonora Leonidovna Dubovitskaya, was born in Leningrad in 1938. She didn’t leave Leningrad, was in town throughout the period of the blockade. She is not Jewish. Her native language is Russian; she graduated from the Leningrad University in 1963, the Philology Faculty, German language department. She worked as a teacher at school, and later as an interpreter in Inturist [organization of foreign tourism]. Now she is a pensioner. We didn’t have children together and she had no children before.

My children have not received a Jewish education, but realize their Jewish roots, Anatoly – on his father’s side, and Vitaly – on both his father’s and mother’s side. Vitaly immigrated to the USA when he was 19, completed a university in Boston and became a programmer. We have managed to keep warm relations with him. He has never been to Russia since. We exchange letters and telephone calls, congratulating each other on Jewish holidays, which he observes, not being religious. Vitaly is married, but has no children so far.

My son Anatoly first obtained basic legal education in a sort of vocational school. It means he received the right to act as a legal adviser, but not as a judge or lawyer. He was very much attracted to the legal profession. It might have got something to do with his genes, and so he continued to study in the Faculty of Law of Leningrad University. Now he has two professions according to his military ticket: driver and lawyer. He is not officially married and has no children. So I have no grandchildren yet. We regularly meet with Anatoly, we recently celebrated his birthday in the Jewish restaurant ‘Pearl’ in Vasilievsky Island.

There was a funny incident in 1970. We received a letter from Geneva, from the International Red Cross, sent to our pre-war address in Zagorodny Avenue with a request: whether there still was anybody by the name of Len living in that apartment. They asked to respond to the Red Cross, which worked on behalf of some of our aunts, nee Len, but it was not specified, where she lived, in Israel or in America. And one of the Russian elderly ladies who lived in that apartment at the time was enterprising enough to pick this letter out from the common post box, took it to the address bureau, found the address of my father, living on the other end of town with his Russian wife, and brought him this letter, dumbfounding the whole family.

After she left, an urgent council of relatives was convened, where they had been deciding whether they should answer the letter or not, and if it was to be answered, who should do it. My stepmother said, ‘We should respond. How do you know that it’s not about an inheritance? But my husband certainly wouldn’t do it, you chose someone between yourselves.’

The die was cast and Uncle Samuel was chosen. He worked at the Metal Plant in the department of the chief technologist in the post of head engineer at that moment. He was a member of the Communist Party, a participant of the Great Patriotic War, a deserved and respected man awarded with the Order of Glory – not everyone was given such a high award – and many medals. It was decided that he would answer. Samuel wrote, that his mother Gitsa was no longer alive, but other relatives were OK, and gave the address, to which it was possible to write.

After that Samuel received a letter with expressions of gratitude that we had responded and a photo of very elderly people, our Polish relatives, who at one time left Poland, yet not for Russia, but for America. And one month later Uncle Samuel was summoned to the appropriate department at work, and was denied access to confidential materials - that was a kind of punishment for connection with relatives living abroad 23. Unfortunately, communication with these relatives was interrupted, and my sister, having arrived in the USA in 1998, could not find anybody with this surname.

In 1980 I decided to check myself if there were any relatives of ours by the name of Skurnik still living in America, and wrote a letter to the United States. I received an answer to my home address. It happened to be my father’s cousin, also born in Poland in 1920. After Western Belarus was annexed to Russia, he became a Soviet citizen, and took part in the war on the side of the Red Army. In 1945, after the war was over, he took advantage of his right to go to Poland where he was born, and through Poland he moved to America.

Then for some time this correspondence was interrupted. But in the meanwhile another thing happened. My sister was suddenly summoned to the special department at her place of work and charged with serious accusations based on the fact that her relatives were corresponding with people from the USA. She was even deprived of the opportunity to work with secret materials, which meant for her the loss of certain privileges and a possible dismissal from her job. She burst into tears and said that she was absolutely innocent, not implicated in anything and knew nothing. They told her, ‘Your brother receives letters from two people abroad.’ They told her the names.

She came to me in tears: ‘What have you done? You are going to ruin all of us! There are two people writing to you from America.’ I said, ‘Tell them that it’s not two persons, it’s the first and the second name of one and the same man, that this man had served in the Red Army, was a soldier on the Soviet side and is a friend of the Soviet Union, not its enemy. At present he is already retired, and there mustn’t be any claims against you.’ But still they lowered her degree of access to information, complicating her work to a certain extent, but her direct boss, respecting her business qualities, kept her at work all the same, actually saving her family from big trouble. And the officer, who wanted to gain promotion and show that he had found a ‘leak’ of information at his enterprise, did not receive the next ‘star’ on his shoulder straps, as this affair was not really credited to him.

Now I correspond with my relatives living abroad, but I no longer have a job to be dismissed from, because my wife and I are both pensioners. I work in Hesed as a volunteer in the ‘Consulting program,’ I read lectures on Yiddishkeit and the current vital problems.

My mother and father were not religious people, both of them graduated from Soviet universities in which atheism was taught. Religious convictions were then frowned upon and even persecuted. I was brought up in the same manner. I saw ‘Jewish life’ only in my grandmother’s home, and even she didn’t follow the kosher principles, she only celebrated Jewish holidays. I was very devoted and respectful to my grandmother, appreciating her faith and helping her in every possible way. I brought her matzot from the synagogue, acted as ‘the tenth’ [for a minyan] during prayer at her request, but I never changed my views and she never insisted on that. She was a wise Jewish lady possessing a profound insight into the way of life that we lived.

It is only in recent years that the world began changing and the Soviet Jews started to show interest in their national traditions, forgotten by us in the past. Undoubtedly, the opportunity to visit Israel had a serious influence on me in this respect. I was in Israel in 1994. I liked the country very much. I have a lot of friends there. I am very concerned about what is happening in Israel now.

I am studying literature on Judaism and Jewish history and then pass it all over to other Jews at lectures.

My wife is Russian and we don’t celebrate Jewish holidays at home. But I often attend the synagogue and all events in Hesed and the Jewish Cultural Center – concerts dedicated to Chanukkah and Pesach, each of which are sometimes attended by over 12,000 St. Petersburg Jews in major concert halls of this city.

Glossary:

1 Hesed

Meaning care and mercy in Hebrew, Hesed stands for the charity organization founded by Amos Avgar in the early 20th century. Supported by Claims Conference and Joint Hesed helps for Jews in need to have a decent life despite hard economic conditions and encourages development of their self-identity. Hesed provides a number of services aimed at supporting the needs of all, and particularly elderly members of the society. The major social services include: work in the center facilities (information, advertisement of the center activities, foreign ties and free lease of medical equipment); services at homes (care and help at home, food products delivery, delivery of hot meals, minor repairs); work in the community (clubs, meals together, day-time polyclinic, medical and legal consultations); service for volunteers (training programs). The Hesed centers have inspired a real revolution in the Jewish life in the FSU countries. People have seen and sensed the rebirth of the Jewish traditions of humanism. Currently over eighty Hesed centers exist in the FSU countries. Their activities cover the Jewish population of over eight hundred settlements.2 Common name

Russified or Russian first names used by Jews in everyday life and adopted in official documents. The Russification of first names was one of the manifestations of the assimilation of Russian Jews at the turn of the 19th and 20th century. In some cases only the spelling and pronunciation of Jewish names was russified (e.g. Isaac instead of Yitskhak; Boris instead of Borukh), while in other cases traditional Jewish names were replaced by similarly sounding Russian names (e.g. Eugenia instead of Ghita; Yury instead of Yuda). When state anti-Semitism intensified in the USSR at the end of the 1940s, most Jewish parents stopped giving their children traditional Jewish names to avoid discrimination.3 NEP

The so-called New Economic Policy of the Soviet authorities was launched by Lenin in 1921. It meant that private business was allowed on a small scale in order to save the country ruined by the Revolution of 1917 and the Russian Civil War. They allowed priority development of private capital and entrepreneurship. The NEP was gradually abandoned in the 1920s with the introduction of the planned economy.4 Gulag

The Soviet system of forced labor camps in the remote regions of Siberia and the Far North, which was first established in 1919. However, it was not until the early 1930s that there was a significant number of inmates in the camps. By 1934 the Gulag, or the Main Directorate for Corrective Labor Camps, then under the Cheka's successor organization the NKVD, had several million inmates. The prisoners included murderers, thieves, and other common criminals, along with political and religious dissenters. The Gulag camps made significant contributions to the Soviet economy during the rule of Stalin. Conditions in the camps were extremely harsh. After Stalin died in 1953, the population of the camps was reduced significantly, and conditions for the inmates improved somewhat.5 Struggle against religion: The 1930s was a time of anti-religion struggle in the USSR. In those years it was not safe to go to synagogue or to church. Places of worship, statues of saints, etc. were removed; rabbis, Orthodox and Roman Catholic priests disappeared behind KGB walls.