Israel Shlifer

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Date of interview: June 2003

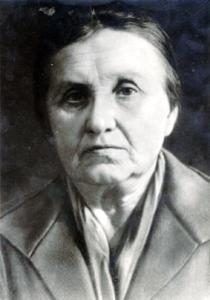

Israel Shlifer is a gray-haired skilful man with keen eyes. He lives alone in a two-room apartment in the very center of Kiev. He has many books placed in bookcases and on bookshelves; most of them are Russian and Soviet classics. There are two portraits on the wall: Israel’s mother and wife. He also has a collection of pictures by Feldman, a Russian watercolor painter. Israel talks with me in a friendly way. He tells me that he is not going to tell about his own life since he had a sensitive governmental position related to weapon-development and he has signed a non-disclosure document. As for his personal life, he said, it is not meant to be known by outsiders. However, he thinks, it is his duty to speak about his relatives and tell the story of a Jewish family.

My parents came from the town of Rzhishchev on the Dnieper in 70 km from Kiev. It’s a picturesque town on the Dnieper where the Legvich River flows into it. The population of Rzhishchev at the beginning of XX century was about 20 thousand people and over 12 thousand of them were Jews. Most of Jewish families resided in the central part of the town. There was a church in the central square and there was a market place open on weekends. Farmers from neighboring villages sold their products: meat, dairies, vegetables, potatoes and honey. Jews had small shops selling tools, hardware and haberdashery. Jews also had professions of tailors, shoemakers, joiners and glasscutters. There was a synagogue in the town. It was a one-storied wooden building located at the spot where the Legvich flows into the Dnieper. In general Rzhishchev was no different from dozens other Jewish towns within the Pale of Settlement [1] in the south of Russia. Nicknames were so common that often people forgot each other’s names given at birth. I liked one man’s nickname. He was Yania Papadoma. When he was returning home after his service in the tsarist army he asked some people that he met on his way, ‘Papa doma?’ (Russian: ‘Is Father at home?’) in Russian since he forgot his Yiddish a little. From then on he was called Yania Papadoma and his children and grandchildren adopted this nickname as their last name. There was Jewish, Russian, Ukrainian, Polish and German population in Rzhishchev. Germans lived in their colony and there was even an enterprise with only German employees in the town.

My father’s parents Idel and Basia Shlifer lived in the lower town that was a Jewish district. They were born in Rzhishchev in 1870s. I knew grandfather Idel when he lived in Kiev and my grandmother died long before I was born. My father and our relatives told me that grandfather Idel came from a Hasidic [2] family. One of his cousins was a rabbi of the Moscow synagogue. My grandfather was deeply religious and could interpret the Torah and the Talmud. He spent his days at the synagogue. He had a big thick beard and payes. He wore a kippah or a big black hat when it was cold. My grandmother was as religious as my grandfather. She prayed at home, went to synagogue and always wore kerchiefs: she had different kerchiefs for cold and warmer days, for wearing at home or going out. Grandmother Basia was a housewife. My grandparents had six children. My father told me that his family was poor. They lived on what the community provided. Of course, they observed Jewish traditions: followed kashrut and celebrated Saturday and Jewish holidays. Grandfather Idel tried to raise his children religious, but the Revolution of 1917 [3] changed their life. Young Jewish people from poor families got fond of communist ideas. They wanted to leave smaller towns for bigger ones. They became communists and apologists of the new communist society.

My father was the only son in the family. His oldest sister, whose name I don’t know, died in infancy. My father had four younger sisters: Esther, born in 1900, Bertha, born in 1902, Nechama, born in 1904, and Bluma, born in 1906. All girls were taught Jewish traditions and holidays and were raised to become housewives and housekeepers. In 1918 grandmother Basia died. All children accepted the Soviet power. They went to a Russian school and gave up religion as vestige of the past. In early 1920s my father’s sisters joined Komsomol [4]. Bertha, Nechama and Esther went to work at a communist construction site in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan in Central Asia [about 3200 km from Kiev]. They lived their life there. Esther became a doctor. She got married and her children Yuliy and Sophia got a higher education. Yuliy lives in St. Petersburg and Sophia and her family moved to Israel in 1990. Bertha, affectionately called Busia at home, became an economist. Her husband Medzievich, a Jewish man, was a doctor and was at the front during the Great Patriotic War [5]. He was wounded and stayed in a frontline hospital. Their older daughter Sarra lives in Israel, Mila lives in Samarkand and their son Lyova lives in Tashkent. They also got higher education. My father’s sister Nechama was single. Esther and Bertha died in Tashkent in 1970s and Nechama died in Tashkent in 1980s. My father’s sister Bluma stayed in Rzhishchev. She became an economist in a book agency in Kiev. She died in the middle of 1980s. Her son Yuri Rentovich lives in Germany.

After my grandmother died my grandfather stayed in Rzhishchev for few years. When in the middle of 1920s struggle against religion [6] began and the synagogue in Rzhishchev was closed he moved to Kiev where he remarried and had two children: daughter Raya and son David. I had no contacts with them. My acquaintances that knew them told me that Raya lives in Germany and David lives in Tashkent. My grandfather’s family in Kiev was poor. Grandfather’s older children and my father supported them. Grandfather Idel died in 1934.

My father Iosif Shlifer was born in 1899. He received a religious education. He finished cheder and a Jewish primary school in Rzhishchev. Then he finished a Realschule [7] in Pereiaslav Khmelnitski. In early 1920s my father moved to Kiev and worked in the system of public education. He also joined the Bund [8]. It merged with the Communist Party in 1920s. My father was a devoted communist for the rest of his life. I don’t know how my parents met. I think they met through matchmakers that was a customary way in Jewish families. They got married in 1921.

My mother Reizl Polisskaya, Rosa, as she was commonly called, also came from Rzhishchev. Her father Beniamin Polisski was a wealthy man. He owned an agricultural equipment plant that he inherited from my great grandfather Gershl Polisski. The plant was on a hill and there was also my grandfather’s house where I grew up. There were Russian and Ukrainian employees at the plant. My grandfather was born in Rzhishchev in 1870. He used to joke that he was born in the same year with Lenin. My grandfather got a religious and professional education. He was good at engineering and management. I know that my grandfather had many brothers and sisters that also worked at his plant. I don’t know their names. The surname of Polisski was quite known in the area. Children of my relatives became engineers, literature critics and one became professor of cardiology in Kiev.

My grandfather and his family lived in a big brick house. There were four big rooms and a big storehouse where the family kept food stocks. There was a kitchen garden and an orchard near the house. They also kept chicken and ducks. Russian and Ukrainian employees came to take care of the garden and livestock and my grandfather repaired their agricultural equipment at his plant in return for their services. My grandfather got along well with his Russian and Ukrainian employees and customers. They rescued my grandfather’s family when in 1918 gangs [9] of ataman Zeleny [10] made a pogrom in Rzhishchev. A Ukrainian family gave my grandfather and grandmother shelter in their house. Only their son Mutsia, one of their sons, stayed at home. When bandits came to the house he treated them with self made vodka and they got drunk and left the house saying that they did not rob good people.

My mother’s family wasn’t as religious as my father’s parents. However, they observed all Jewish traditions: they followed kashrut. They also celebrated Sabbath, but it was more like tribute to tradition and an opportunity for the family to get together. In summer my grandfather and his sons had to do work on Saturday. Grandfather Beniamin prayed every day with his tallit and tefillin on. Grandmother Chaika was a housewife like all Jewish women. She also managed housemaids and employees in the house.

There were seven children in the family. My mother was the only daughter. My mother’s older brothers were married and lived in their own houses. My grandfather built houses for his sons when they were getting married. All of the sons had Jewish wives. It couldn’t have been otherwise. They had Jewish weddings with a rabbi, chuppah and klezmer musicians. I knew my uncles’ affectionate names, by which they were called in the family. The older one Elia, Ilia Polisski, was born around 1895. The next was Bozia, Chaim Moshka, born in 1897, and then came Lev, born in 1898. They were my mother’s older brothers. They finished cheder like all Jewish boys in the town. My mother’s brothers weren’t religious when I knew them. They were highly skilled craftsmen. They had no problem fixing any piece of equipment and they could work at lathe units and could do joiner work. They worked at my grandfather’s plant until early 1930s when it was liquidated after the NEP [11]. Then they went to work at state owned enterprises. During the Great Patriotic War my mother’s brothers and their families were in evacuation in Tashkent. Lev didn’t have any children. He and his wife died in the middle of 1970s. Ilia and Chaim both had a son with the name Mark. Ilia’s son became a professional in the military. He was at the front during World War II. After the war he was a foreman at a military plant in Kiev. Uncle Ilia lived with his son Mark and his family after the war. Uncle Ilia and uncle Chaim died in Kiev in the middle of 1960s. They buried at the Jewish part of the town cemetery. Mark, uncle Chaim’s son, finished a Polytechnic in Leningrad and worked at the aviation plant in Kiev. He died young of infarction.

My mother’s younger brothers Avraam (affectionately called Mutsia), born in 1902, Boruch (Boris), born in 1904, and Mendel, born in 1907, got higher education. They were at the front during the Great Patriotic War. After the war they lived in Kiev. Avraam was a foreman at the Arsenal Military Plant in Kiev and lived in a nice and big apartment. He died in the middle of the 1980s. His son Arkadi lives in Israel and his daughter Maya – in Germany. Boruch finished the Polytechnic and lived in Kiev with his wife Liya and daughter Sophia. He died a long time ago. Sophia lives in Israel. Uncle Mendel, whose common name [12] was Michael, finished a Construction College and built bridges. He got married before the war, but when his wife heard that he was severely wounded and became handicapped she left him. After the war Uncle Mendel lived with me in a small 16 square meter room that the plant where I was working gave me when I was a young promising scientist. Мendel died in 1982. He was buried near his older brothers’ graves.

My mother was born in 1900. The only daughter, she was everybody’s favorite in the family. She finished a Jewish primary school and a school for girls. She had music lessons at home. She had Karl Bluthner grand piano bought particularly for her to study music. She also had German classes with a teacher that came from the German colony [13]. In 1917 my mother moved to Kiev. She lived in grandfather Beniamin’s apartment in Nizhni Val Street in Podol [14]. Grandfather supported her. I think it was probably there where she met my father.

They got married in Rzhishchev in 1921. Although my father wasn’t religious they had a traditional Jewish wedding with a rabbi and chuppah and everything else that had to be at a Jewish wedding. After the wedding my parents went to Kiev where my father worked at the department of education and studied at the Faculty of Mathematics at the University. They lived in the apartment where my mother lived before she got married.

I was born in Kiev in 1922. It was a hard time shortly after the Civil War [15]: destitution, hunger and destruction. My father worked and studied and came home late at night. My mother and I went to Rzhishchev. I stayed there until the age of 6 and my mother returned to Kiev. She entered the Faculty of Philology at the University and I stayed with my grandfather and grandmother. My parents came to visit us on my birthday and on Soviet holidays when they didn’t have to go to work or study. I enjoyed being with my grandparents. I was their favorite. My grandmother and grandfather and numerous relatives were spoiling me. Even when I banged on my mother’s grand piano with my feet or stole my grandfather’s little boxes [tefillin] that he put on his hand and head to pray they didn’t tell me off. My mother explained to me that there were little scrolls of the Torah in those boxes and that I was not allowed to touch them. [Editor’s note: Not the whole Torah, but two passages from Deuteronomy and two from Exodus, in which Jews are required to put ’these words’ (of the Law) for ’a sign upon thy hand and a frontlet between thine eyes’ are put int he teffilin.] From then on I enjoyed watching my grandfather putting on his beautiful tallit and tefillin, taking his book of prayers and praying rocking to the sides. While doing this he kept watching workers in the yard giving directions to them every now and then. Even then it seemed to me that my grandfather was praying following the rules rather than feeling the need to pray. On Saturday my mother’s family got together to have a festive meal. Her older brothers came with their families. I do not remember my grandmother lighting candles on Friday. Perhaps, I was too young to pay attention to this. The family also celebrated Jewish holidays. The only one I remember was Chanukkah. I remember it since we got money gifts on this holiday. It was a joyful holiday, but I only learned the history of this holiday as well as other Jewish holidays recently. At the age of 6 my parents took me to Kiev where I went to kindergarten since my parents believed that a child had to get used and develop in a collective of other children.

My father finished the University and became a financial officer within the Ministry of Industry. He often traveled on job assignments to other towns and then I went to Rzhishchev since my mother followed my father. My parents traveled to many towns: Dnepropetrovsk, Dneprodzerzhinsk and Kharkov where my father held official posts.

In early 1930s the state nationalized [16] my grandfather’s plant and house. We were happy that they didn’t arrest him. My grandfather Beniamin and grandmother moved to Kiev and settled down in their apartment in Nizhni Val. My parents had their own apartment and when they had to travel to another town they left me with my grandparents. My mother’s younger brothers Avraam, Boris and Mendel lived with them. In sometime my grandfather’s plant and house were burnt down. I don’t know who or why did this. During famine in 1932 [Famine in Ukraine] [17] my uncles, grandmother and grandfather returned to Rzhishchev where they hoped it was easier to survive. They only found ashes of their big house with my mother grand piano’s frame. We moved into one of my uncles’ house. My mother’s brothers and their wives worked hard growing vegetables to feed the family. In winter we found dead people on the porch of our house. They knew how kind our family had always been and hoping to find shelter they fell asleep and died from cold and hunger. My grandmother kept her door open for starving people and shared no matter how little we had. Fortunately, all members of our family survived.

That same year my father got a job assignment to Mariupol and took me with him. From then on I lived with my parents. We often moved from one town to another and I changed schools. My first school in Kiev was Russian, then I went to a Ukrainian school in Rzhishchev and then I lost count of them. We lived in Ukrainian and Russian towns. One of them was Magnitogorsk in Siberia. I enjoyed my studies and liked all subjects.

In 1937 we moved to Kiev for good. My mother and I came first and then my father returned in a year’s time. We lived in my grandfather Beniamin’s apartment. Grandfather returned to Kiev in 1934 after the famine was over. Grandfather sold his apartment in Nizhni Val and bought a smaller one in Spasskaia Street. Grandfather worked in a joiner shop. My grandparents didn’t have much to live on. I liked to go to work with him. I liked it more than going to school. In Kiev my grandmother and grandfather celebrated Jewish holidays. One of them was Pesach. However, my grandfather stopped praying. He didn’t wear a kippah any longer and my grandmother didn’t cover her head. On some big holidays she went to synagogue. Sometimes I went to visit my paternal grandfather Idel with my grandfather Gersh. If we had to wait until grandfather Idel finished his prayer my grandfather Gersh winked at me mocking the excessive, as he saw it, religiosity of Idel. Nevertheless, grandfather Gersh treated Idel with respect and sympathy and often supported him. In early 1941 grandmother Chaia died. All relatives, even my father’s sisters from Tashkent came to her funeral. They all loved and respected my quiet grandmother that dedicated her life to her husband and children. From hospital the coffin was taken to the synagogue in Podol where a rabbi recited prayers. After the funeral Beniamin moved in with us. My mother didn’t want him to live alone. He lived with us until the Great Patriotic War.

I became a pioneer and joined Komsomol at school, but I didn’t feel like taking part in any public activities. I didn’t make friends at school. When my father received an apartment in Saksaganskogo Street I made friends with my neighbors and we were lifetime friends. There were two rooms in the apartment that my father received. There was stucco molding on high ceilings. We had neighbors: an old woman that came from a noble family that owned the house before the Revolution of 1917 and her son. My mother became her friend and often went for a cup of tea with her. My mother had a philological education and taught Russian literature and language at school and they had common subjects to discuss with this woman. I also liked listening to her. She told interesting stories about the past, about artists and poets.

At that time I got fond of poetry. My friends were intelligent boys. I learned a lot from them. At first I felt like a ‘black sheep’ with them since I came from a smaller town and my friends were more knowledgeable than I in many areas, but gradually I caught up with them. I became interested in literature and poetry. We were fond of forbidden poets for the most part. At that time all poets, but Mayakovsky [18], Yesenin [19], Gumilev [20], Mandelshtam [21], – were forbidden. We got copies of poems that we read and learned by heart. Somehow the Komsomol organization of my school got to know that we read forbidden poets. Probably one of us reported to them. My friends were called to the leaders where NKVD [22] representatives were present. Fortunately, I didn’t have to go there. They asked the boys where they got copies, but my friends answered that they just heard these poets and remembered them. The officers probably didn’t believe them, but they left them. One boy’s parents were so scared that they sent their son to Moscow for a whole year. We could understand their fear: this was the period of 1937-39 [Great Terror] [23] - arrests of ‘enemies of the people’ [24] that emerged all of a sudden from nowhere. Nobody in our family suffered during this period, but my father expected arrest every day. I don’t think he understood that Iosif Stalin himself was to blame for this outrage that took away millions of innocent lives.

The majority of my mother's relatives and some of my father’s relatives lived in Kiev. They often visited us. We met on birthdays and wedding anniversaries. We also celebrated Soviet holidays: 1st May and the October Revolution Day [25]. The adults danced to Jewish and Soviet records and sang. We didn’t celebrate Jewish holidays at home. Only once a year relatives came to celebrate Pesach with grandfather Beniamin. I didn’t attend the celebrations, and not know, as it was. I preferred my friends’ company.

My friends and I often went to theaters. One of my friends was a son of director of the Theater of the Red Army that was popular before the war. This boy often got free tickets to his father’s theater, Russian or Ukrainian Drama Theaters. Sometimes we had to stand in passageways, but this didn’t matter much to us. We were young and loved theater. We watched Ukrainian and Russian drama performances. We also went to the Jewish theater. Though some of my friends were Russian and we didn’t understand Yiddish we sat beside an old man that interpreted for us. We didn’t give much thought to nationality that actually didn’t matter to us.

In 1939 I finished school with a so-called ‘golden certificate’. There were no medals then and a golden certificate had a golden frame. I was eager to study science – physics- and went for an interview to the Leningrad College of Physics. I had a successful interview, but my mother was against my studying away from home. I obeyed her and submitted my documents to the Kiev Polytechnic College (it was called Industrial College then) to the Faculty of Radio Physics. I was admitted and studied two years in this College. My friends and I knew that fascism came to power in Europe. We saw Professor Mamlock [26] a film about Hitler’s view on Jews. Besides, we, radio physics, always listened to foreign channels. We made radios by ourselves. We had more information about the war in Europe than our newspapers published or radio broadcast. ‘The Voice of America’, ‘Svoboda’ [Freedom in Russian] and a number of other western radios broadcast in Russian, but very few could listen to them due to Soviet security agencies that jammed their programs. Only those that had special radios had an opportunity to listen to western radios. Nevertheless, we didn’t have a feeling that the war was near or that Hitler would attack the Soviet Union. Even lecturers of the Military Faculty in our College said that we had to learn to defend our country, but they never mentioned a possibility of war against fascism.

On 22 June 1941 I came to College to take an exam. All students were requested to gather in a big lecture room. We were told that the 43rd Distillery had been ruined by bombing the previous night and that the war began. Then the military registry office mobilized us to deliver the call-ups. The boards with number of buildings and names of streets were removed from houses for some reasons probably to confuse potential German spies. However, we were the ones that were confused. We had to ask pedestrians about numbers of buildings to deliver subpoenas. Some teenagers that were watchful about spies took us to a militia department. Of course, militia found out who we were in an instant.

In early July my parents moved to Kharkov where all managerial offices, including my father’s Ministry, moved. My grandfather and other relatives went to Tashkent [Uzbekistan, about 3200 km from Kiev] to my father’s sisters. My co-students and I were mobilized to Kiev Territorial Army [Fighting battalion] [27]. We excavated anti-tank trenches in the southern direction. For many years there was a lake formed where we excavated trenches. There were continuous air raids and in the middle of August I was wounded in my back with a bomb splinter. I was taken to Kharkov by a sanitary train. I found my father there. I was released from military service due to my wound. My father sent me to Tashkent. I traveled in a sanitary train for slightly wounded. Our trip lasted 10 days. We were taken to a hospital in Tashkent where I stayed another month. Then I stayed with my paternal aunts.

In late September 1941 my parents came to Tashkent too. We were glad to be together, but we were sad that fascists occupied Kiev.

My father went to work as Financial Manager at the Ministry of Light Industry and my mother became a teacher in a Russian school. My father got a good apartment and my grandfather stayed with us. My father received a special food package as a high governmental official.

In some time I went to Polytechnic to continue my studies as a third-year student. This College was formed by Kiev, Tashkent and Leningrad Colleges. By that time my mother’s brothers and their families, my father’s sister Bluma and her son and uncle Mendel that returned from the front as an invalid were living with us. There was too little space and I went to live at the students’ hostel. I received a stipend and did some work to earn additional money. Third-year students worked as electricians at food enterprises. I worked at the confectionery and my friend Tolia worked at a bakery. Girls wrote synopsis of lectures for us and we shared with them what we stole at work. We read poems and went to theaters. I liked the Moscow Jewish Theater that was in evacuation in Tashkent. I watched all performances with the legendary Mikhoels [28] playing main roles. Mikhoels greeted me when he met me in town. He probably remembered me seeing me so often at the theater.

In 1944, few months after Kiev was liberated the Kiev Polytechnic College reevacuated to Kiev. We had a choice between Central Asia, Kiev or Leningrad Colleges. I got an offer to go to Kiev. They promised me work in College. The train trip to Kiev took us almost a month, but the feeling was very different from when we were leaving the city. My parents, grandfather and uncle Mendel stayed in Tashkent. My father didn’t want to leave his high post. Kiev was in ruins. Our house was ruined, too. I stayed at a student hostel. In some time I found some of my friends. We were together again. I finished College in 1945. I was a promising employee and got an offer to write thesis in College, but there was no chance for me to get an apartment working in college. Therefore, I went to work at the military instrument manufacture plant called Communist where I became head of laboratory. I also worked part-time in College. The plant gave me a 16 square meter room in a shared apartment [26]. My grandfather Gershl and my uncle Mendel came back from Tashkent and stayed with me. My grandfather was cheerful and optimistic until his last days. He made friends among our neighbors. They were older people. They met and had long discussions on a bench near the house or having a cup of tea at home. Grandfather went to synagogue on Sabbath and Jewish holidays, but he didn’t pray at home. We didn’t follow kashrut. We were glad to have any food at all. I had meals at the canteen at my plant. I bought hot meals to take home to my grandfather and my uncle. My grandfather died in 1952 at the age of 82. We buried him at the town cemetery.

I worked at the Communist Plant several years. I had a sensitive job and often met with high officials. I met several times with the General Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party, Nikita Khrushchev [30] that became General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR in 1953. Those were business meetings, but I liked Khrushchev. I still know no explanation of how I kept my job when in 1949, at the height of state anti-Semitism and during the campaign against cosmopolitans [31] my father was arrested in Tashkent and sentenced under a political article of the law. My mother wrote me that he was charged of espionage for Germany and nonsense like that. I understood that my father was innocent. I knew this was a state policy against Jews, but what could I do? I knew that my management had to know about my father’s arrest, but they showed no sign of this and I pretended nothing happened. My father never told me about what he was accused of. They might have remembered his Bund membership. To tell the truth, they didn’t beat him. They used another thing: they kept him in a single cell for the first year. Then his friends managed to help him and my father was taken to a camp near Tashkent. My father actually performed the duties of chief accountant in the camp. He had a privilege: he was allowed to sleep on the sofa in his office instead of going back to the barrack. Besides, he made reports to the bank management. They spoke to him rather than calling an official chief accountant. My father went to the bank with a guard and my mother was waiting there for him with hot lunch. Then my mother moved to Kiev. My father was released in 1954, a year after Stalin died. He was exculpated from all charges.

I went to work at another plant and then changed my job again. I went to work at the New Problems in Physics Academic Institute. I often went on business trips to other plants, Navy bases and airfields. I worked with people that valued talent and work capabilities. They never asked me about my nationality. They had other things to think about. I’ve never faced anti-Semitism in my life. I heard about the Doctors’ Plot [32] by chance when I was on a business trip in Moscow. I was having lunch in the canteen of our Ministry. A colonel at a nearby table said unfolding a newspaper ‘Now they will finally deal with Jews’. I kept silent, but my companion attacked this colonel and gave him a lecture about morals, equality and fraternity of peoples in the USSR guaranteed by the Constitution. In 1953 Stalin died. On the day of his funeral I was on a short stay in Moscow traveling from a business trip from the Far North. I wore a sheepskin coat and deerskin boots. This outfit saved my friend and me when we got in a jam in Pushkin Square during the funeral. We got under a trolley bus and stayed there. Otherwise we would have been smashed by the crowd. Hundreds of people died there. Stalin’s death wasn’t a tragedy for me. I understood that Stalin was to be blamed for my father’s arrest and for the suffering of millions of people. I also knew that he must have been aware of the recent anti-Semitic campaigns. Denunciation of the cult of Stalin and the speech of Nikita Khrushchev in 1956 at the 20th Party Congress [33] were not big surprises for me. Although I wasn’t a member of the Party, we knew about this secret Khrushchev’s speech that was only to be read in Party organizations, on the first day after Congress from our friends that were communists. It was like new wind blowing in our country. Nevertheless, I still think that Stalin had a strong personality and was an unusual man. It’s a different story where he applied his strength and talent.

In 1954 I went to Moscow to pick up my father. He came to Moscow after he was released and stayed with his distant relative that was a rabbi in a synagogue in Moscow. My father was eager to go to the Mausoleum to see Stalin: imagine this devotion and faith after all he had to go through! Until the end of his days he thought that his arrest was a tragic mistake. My father said he wasn’t going home until he saw Stalin. We had to stand in a long line and my father calmed down after he saw dead Stalin.

In Kiev we lived together for some time and then my father received a two-room apartment. My mother and father moved to that apartment. My father went to work as chief accountant at the weaving mill. His arrest and stay in a single cell change my father dramatically. A cheerful man that he was changed to a withdrawn and despondent man. He began to pray. He didn’t pray in the Jewish manner. I don’t think he had a tallit or knew any prayers. He said his own prayers and prayed to his god that he got to know when he was in his cell. Sometimes he went to synagogue, but he didn’t pray there. He just sat there quietly. In 1960s my father got severely ill. He had lymphogranulomatosis that was incurable. He consulted doctors in Kiev and Moscow, but they offered no cure. My father died in 1970. My mother lived many years longer. She died in 1986. Uncle Mendel that lived with me died in 1982.

I cannot talk about my work. My achievements are highly sensitive. Besides, I shall not boast. In early 1950s I defended my candidate dissertation [doctorate]. I was awarded the title of doctor for my scientific achievements. I dedicated my life to my work, although I don’t think I am a scientist, rather just an engineer. I have my achievements and saw the results of my work applied. I have many patents for development that were implemented in industries.

I was a bachelor for many years. Of course, I wasn’t ascetic, but I got married at the age of 45. I married my friend’s sister Alla Bialik, a Jew. Alla is much younger than me. She was born in 1937. Her parents came from Rzhishchev. They were intelligent people. They didn’t observe any Jewish traditions. Alla’s father Wolf Bialik was a distant relative of Chaim Nachman Bialik [34], one of the greatest Jewish poets. There were literary and theatrical critics and doctors in Alla’s family. During the Great Patriotic War Alla and her parents were in evacuation somewhere in the Ural. After the war they returned to Kiev where she finished secondary school and the Kiev College of Economics. She worked as chemical engineer. We exchanged my small apartment into the one where I live now. We had a good life, although we didn’t have children. We got married at a respected age and we just shared the warmth of our souls. I earned well and we could afford to spend vacations at the best recreation homes in the country. We went to concerts and theaters. We also had a dacha [cottage], but we had to sell it since doctors didn’t allow me any physical strain after an eye surgery. We didn’t have a car since I could use my office car if I had such need. I’ve collected pictures of my favorite German watercolor painter, Feldman. Regretfully, Alla died of cancer in 1992. Now I am alone.

I still do some consulting at the Military Academy and write articles and books. I cannot live without work. For this reason I didn’t emigrate to Israel in or the USA where I have many relatives. Of course, I was interested in Israel as a historical motherland and the nucleus of the Jewish People. In 1960s-70s when Israel was in the state of numerous wars with the Arabs, when just the word ‘Israel’ provoked a mock and hostility of our official policy, I was for Israel like all reasonable people. I watched this country develop and wished that it gained victory. For many years I was not allowed to travel abroad due to my knowledge of state secrets. I did know many developments of weapons. Finally in 1996, when our human resource manager was on vacation, the director of my institute signed my permit to travel abroad. He had known me for many years and was sure that I was not going to share any secrets. I traveled to Israel. I liked it there, but I understood that I could only live in my country where I was born and had lived a long life.

I have a twofold attitude to perestroika [35] that changed the life of the country and its people dramatically. It’s not that I worry about the material part of life. I still work and can earn money and I receive a sufficient scientific pension, but I feel sorry for other old people tat have to lead a miserable life after they had worked for 40 years or more. I am glad that perestroika opened up opportunities for the development of national cultures, including the Jewish one, the so-called minority culture. I am also glad about democratic principles coming into our life and that the iron curtain [36] collapsed and people have got an opportunity to see the world. However, I still feel sorry for the downfall of the Soviet Union. I loved the integral country. I have many friends all over the country [the former Soviet Union]. Now there are borders and customs between us. I cannot jump on a train to go to the Baltic Republics. I need a visa and a foreign passport… I cannot accept this.

Now that independent Ukraine gave a real opportunity for the development of the Jewish cultural life I began to participate in it. I am an active member of Bnai Brith [37] I take every effort to make this organization a real hearth of Jewish culture. I celebrate Jewish holidays, go to Seder at the synagogue and read Jewish newspapers. Besides, I collect Jewish folk music and study Jewish traditions from tapes. This is all very interesting, but I’ve never concentrated on purely national attitudes. I have many Russian and Ukrainian friends. They are active in science and culture. I believe I am a citizen of the Universe and I value every human being regardless of their national origin.

GLOSSARY:

[1] Jewish Pale of Settlement: Certain provinces in the Russian Empire were designated for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population (apart from certain privileged families) was only allowed to live in these areas.

[2] Hasid: The follower of the Hasidic movement, a Jewish mystic movement founded in the 18th century that reacted against Talmudic learning and maintained that God’s presence was in all of one’s surroundings and that one should serve God in one’s every deed and word. The movement provided spiritual hope and uplifted the common people. There were large branches of Hasidic movements and schools throughout Eastern Europe before World War II, each following the teachings of famous scholars and thinkers. Most had their own customs, rituals and life styles. Today there are substantial Hasidic communities in New York, London, Israel and Antwerp.

[3] Russian Revolution of 1917: Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during WWI, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.

[4] Komsomol: Communist youth political organization created in 1918. The task of the Komsomol was to spread of the ideas of communism and involve the worker and peasant youth in building the Soviet Union. The Komsomol also aimed at giving a communist upbringing by involving the worker youth in the political struggle, supplemented by theoretical education. The Komsomol was more popular than the Communist Party because with its aim of education people could accept uninitiated young proletarians, whereas party members had to have at least a minimal political qualification.

[5] Great Patriotic War: On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.

[6] Struggle against religion: The 1930s was a time of anti-religion struggle in the USSR. In those years it was not safe to go to synagogue or to church. Places of worship, statues of saints, etc. were removed; rabbis, Orthodox and Roman Catholic priests disappeared behind KGB walls.

[7] Realschule: Secondary school for boys in Russia before the revolution of 1917. Students studied mathematics, physics, natural history, foreign languages and drawing. After finishing this school they could enter higher industrial and agricultural educational institutions.

[8] Bund: The short name of the General Jewish Union of Working People in Lithuania, Poland and Russia, Bund means Union in Yiddish). The Bund was a social democratic organization representing Jewish craftsmen from the Western areas of the Russian Empire. It was founded in Vilnius in 1897. In 1906 it joined the autonomous fraction of the Russian Social Democratic Working Party and took up a Menshevist position. After the Great October Socialist Revolution the organization split: one part was anti-Soviet power, while the other remained in the Bolsheviks’ Russian Communist Party. In 1921 the Bund dissolved itself in the USSR, but continued to exist in other countries.

[9] Gangs: During the Civil War in 1918-1920 there were all kinds of gangs in the Ukraine. Their members came from all the classes of former Russia, but most of them were peasants. Their leaders used political slogans to dress their criminal acts. These gangs were anti-Soviet and anti-Semitic. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.

[10] Zeleny, one of the atamans (headmen) loosely associated with the Ukrainian nationalist military leader Simon Petlura. His real name was Danilo Trepilo. Zeleny, which means green in Russian, was the nickname he received during the days of the Hetman, since he spent time hiding in the green valleys near his village. This would remain his pseudonym. Green, the color of the fields and forests, became the symbolic color of the peasant uprisings. Zeleny appeared at the same time as Atamans Angel, Sokolovski, and Struk, but he played a much more important role than they did. He had greater organizational skills and more ambition. He surrounded himself with a larger group of rebels and spread himself over a wider territory. Ataman Grigoriev, who began the large uprising in May, strove harder than Zeleny, but his rule did not last long. He was quickly liquidated, while Zeleny’s uprising lasted from the end of March until September 1919. Zeleny was the prototypical representative of the rebel movement from the Ukrainian villages of this period.

[11] NEP: The so-called New Economic Policy of the Soviet authorities was launched by Lenin in 1921. It meant that private business was allowed on a small scale in order to save the country ruined by the October Revolution and the Civil War. They allowed priority development of private capital and entrepreneurship. The NEP was gradually abandoned in the 1920s with the introduction of the planned economy.

[12] Common name: Russified or Russian first names used by Jews in everyday life and adopted in official documents. The Russification of first names was one of the manifestations of the assimilation of Russian Jews at the turn of the 19th and 20th century. In some cases only the spelling and pronunciation of Jewish names was russified (e.g. Isaac instead of Yitskhak; Boris instead of Borukh), while in other cases traditional Jewish names were replaced by similarly sounding Russian names (e.g. Eugenia instead of Ghita; Yury for Yuda). When state anti-Semitism intensified in the USSR at the end of the 1940s, most Jewish parents stopped giving their children traditional Jewish names to avoid discrimination.

[13] German colonists: Ancestors of German peasants, who were invited by Empress Catherine II in the 18th century to settle in Russia.

[14] Podol: The lower section of Kiev. It has always been viewed as the Jewish region of Kiev. In tsarist Russia Jews were only allowed to live in Podol, which was the poorest part of the city. Before World War II 90% of the Jews of Kiev lived there.

[15] Civil War (1918-1920): The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti-communist groups – Russian army units from World War I, led by anti-Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.

[16] Nationalization: confiscation of private businesses or property after the revolution of 1917 in Russia.

[17] Famine in Ukraine: In 1920 a deliberate famine was introduced in the Ukraine causing the death of millions of people. It was arranged in order to suppress those protesting peasants who did not want to join the collective farms. There was another dreadful deliberate famine in 1930-1934 in the Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from the peasants. People were dying in the streets, whole villages became deserted. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious peasants who did not want to accept Soviet power and join collective farms.

[18] Vladimir Mayakovsky: Born in July 19 [July 7, Old Style], 1893, Bagdadi, Georgia, Russian Empire—died in April 14, 1930, Moscow), the leading poet of the Russian Revolution and of the early Soviet period. Mayakovsky was, in his lifetime, the most dynamic figure of the Soviet literary scene, but much of his utilitarian and topical poetry is now out of date. His predominantly lyrical poems and his technical innovations, influenced a number of Soviet poets, and outside Russia his impress has been strong, especially in the 1930s, after Stalin declared him the "best and most talented poet of our Soviet epoch."

[19] Yesenin, Sergei Aleksandrovich,1895–1925, Russian poet. Yesenin was the most popular poet of the early revolution and the object of a considerable cult. He belonged to the imagist school, advocating absolute independence for the artist. Yesenin is known for his simple lyrics about village life and the Russian landscape. His epic Pugachev (1922) is a verse tragedy concerning the peasant rebellion of 1773–75. After welcoming the revolution, he rejected the policies of the Bolshevik regime. In 1922 Yesenin married Isadora Duncan and toured the United States and Europe. After they separated he married a granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy. At 30 he committed suicide.

[20] Gumilev, Nikolay Stepanovich, born April 15, 1886 , Kronshtadt, Russia

died Aug. 24, 1921 , Petrograd [St. Petersburg] Russian poet and theorist who founded and led the Acmeist movement in Russian poetry in the years before and after World War I.

[21] Osip Mandelshtam (1891-1938) Soviet poet, who was born in Warsaw, but raised with his two brothers in the cultural milieu of St. Petersburg's bourgeois intelligentsia. In St. Petersburg, he attended both Vyacheslav Ivanov's Tower and meetings of the St. Petersburg Society of Philosophy. His first published poems appeared in August 1910. In 1933 Mandelshtam wrote a poem, which will be the cause of his arrest and, ultimately, death. The official date given on Mandelshtam's death certificate is 27th December 1938. The poem, called "We are living, not feeling the country under us" talked about the realities of Stalinist Russia.

[22] NKVD: People’s Committee of Internal Affairs; it took over from the GPU, the state security agency, in 1934.

[23] Great Terror (1934-1938): During the Great Terror, or Great Purges, which included the notorious show trials of Stalin's former Bolshevik opponents in 1936-1938 and reached its peak in 1937 and 1938, millions of innocent Soviet citizens were sent off to labor camps or killed in prison. The major targets of the Great Terror were communists. Over half of the people who were arrested were members of the party at the time of their arrest. The armed forces, the Communist Party, and the government in general were purged of all allegedly dissident persons; the victims were generally sentenced to death or to long terms of hard labor. Much of the purge was carried out in secret, and only a few cases were tried in public ‘show trials’. By the time the terror subsided in 1939, Stalin had managed to bring both the party and the public to a state of complete submission to his rule. Soviet society was so atomized and the people so fearful of reprisals that mass arrests were no longer necessary. Stalin ruled as absolute dictator of the Soviet Union until his death in March 1953.

[24] ‘Enemy of the people’: an official definition for political prisoners in the USSR.

[25] October Revolution Day: October 25 (according to the old calendar), 1917 went down in history as victory day for the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia. This day is the most significant date in the history of the USSR. Today the anniversary is celebrated as ‘Day of Accord and Reconciliation’ on November 7.

[26] Professor Mamlock: This 1937 Soviet feature is considered the first dramatic film on the subject of Nazi anti-Semitism ever made, and the first to tell Americans that Nazis were killing Jews. Hailed in New York, and banned in Chicago, it was adapted by the German playwright Friedrich Wolf - a friend of Bertolt Brecht - from his own play, and co-directed by Herbert Rappaport, assistant to German director G.W. Pabst. The story centers on the persecution of a great German surgeon, his son’s sympathy and subsequent leadership of the underground Communists, and a rival’s sleazy tactics to expel Mamlock from his clinic.

[27] Fighting battalion: People’s volunteer corps during World War II; its soldiers patrolled towns, dug trenches and kept an eye on buildings during night bombing raids. Students often volunteered for these fighting battalions.

[28] Mikhoels, Solomon (1890-1948) (real name Vovsi): Great Soviet actor, producer, pedagogue. He worked in the Moscow State Jewish Theater (and was its art director from 1929). He directed philosophical, vivid and monumental works. Mikhoels was murdered by order of the State Security Ministry.

[29] Shared apartments: The Soviet power wanted to improve housing conditions by requisitioning ‘excess’ living space of wealthy families after the revolution of 1917. Apartments were shared by several families with each family occupying one room and sharing the kitchen, toilet and bathroom with other tenants. Because of the chronic shortage of dwelling space in towns shared apartments continued to exist for decades. Despite state programs for the construction of more houses and the liquidation of shared apartments, which began in the 1960s, shared apartments still exist today.

[30] Khrushchev, Nikita (1894-1971): Soviet communist leader. After Stalin’s death in 1953, he became first secretary of the Central Committee, in effect the head of the Communist Party of the USSR. In 1956, during the 20th Party Congress, Khrushchev took an unprecedented step and denounced Stalin and his methods. He was deposed as premier and party head in October 1964. In 1966 he was dropped from the Party's Central Committee.

[31] Campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’: The campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’, i.e. Jews, was initiated in articles in the central organs of the Communist Party in 1949. The campaign was directed primarily at the Jewish intelligentsia and it was the first public attack on Soviet Jews as Jews. ‘Cosmopolitans’ writers were accused of hating the Russian people, of supporting Zionism, etc. Many Yiddish writers as well as the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested in November 1948 on charges that they maintained ties with Zionism and with American ‘imperialism’. They were executed secretly in 1952. The anti-Semitic Doctors’ Plot was launched in January 1953. A wave of anti-Semitism spread through the USSR. Jews were removed from their positions, and rumors of an imminent mass deportation of Jews to the eastern part of the USSR began to spread. Stalin’s death in March 1953 put an end to the campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’.

[32] Doctors’ Plot: The Doctors’ Plot was an alleged conspiracy of a group of Moscow doctors to murder leading government and party officials. In January 1953, the Soviet press reported that nine doctors, six of whom were Jewish, had been arrested and confessed their guilt. As Stalin died in March 1953, the trial never took place. The official paper of the party, the Pravda, later announced that the charges against the doctors were false and their confessions obtained by torture. This case was one of the worst anti-Semitic incidents during Stalin’s reign. In his secret speech at the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956 Khrushchev stated that Stalin wanted to use the Plot to purge the top Soviet leadership.

[33] Twentieth Party Congress: At the Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 Khrushchev publicly debunked the cult of Stalin and lifted the veil of secrecy from what had happened in the USSR during Stalin’s leadership.

[34] Bialik, Chaim Nachman: (1873-1934): One of the greatest Hebrew poets. He was also an essayist, writer, translator and editor. Born in Rady, Volhynia, Ukraine, he received a traditional education in cheder and yeshivah. His first collection of poetry appeared in 1901 in Warsaw. He established a Hebrew publishing house in Odessa, where he lived but after the 1917 revolution Bialik’s activity for Hebrew culture was viewed by the communist authorities with suspicion and the publishing house was closed. In 1921 Bialik emigrated to Germany and in 1924 to Palestine where he became a celebrated literary figure. Bialik’s poems occupy an important place in modern Israeli culture and education.

[35] Perestroika: Soviet economic and social policy of the late 1980s. Perestroika [restructuring] was the term attached to the attempts (1985–91) by Mikhail Gorbachev to transform the stagnant, inefficient command economy of the Soviet Union into a decentralized market-oriented economy. Industrial managers and local government and party officials were granted greater autonomy, and open elections were introduced in an attempt to democratise the Communist party organization. By 1991, perestroika was on the wane, and after the failed August Coup of 1991 was eclipsed by the dramatic changes in the constitution of the union.

[36] Iron curtain: Iron curtain: political, military, and ideological barrier erected by the Soviet Union after World War II to seal off itself and its dependent eastern European allies from open contact with the West and other noncommunist areas. In the USSR this was the word for the ban to travel abroad and communicate with foreigners or relatives living abroad. This ban existed in the USSR for over 50 years.

[37] Bnai Brith - the oldest Jewish charity oranization. The name means ‘sons of the Testament’ in Ivrit. Its purpose is to unite people professing Judaism and present their interests and the interests of mankind, develop spiritual and moral education of coreligionists and spread philanthropic ideas. It was founded in USA in 1843. It opened its affiliates in the former Soviet Union and in Ukraine in early 1990s. Its members are activists of science, culture and the goal of this organization is provision of assistance, but even more so - restoration of the Jewish culture, interest to Jewish history, religion, etc.