Mojsze Sznejser is an 84-year-old cobbler, who still works in his own workshop in Legnica. He comes from a small town called Lukow. Before World War II he lived and worked in Warsaw, and after surviving the Holocaust in the USSR he moved to Legnica, a town in south-western Poland, where he is a member of the local Jewish community. During our four meetings in his workshop and his apartment, he shared with me his memories of his large family, and sketched a picture of Jewish life in pre-war Lukow and post-war Legnica. His narrative style is very laconic, that is why his story appears short, but in his frank, simple words there's a certain hidden logic and coherence. These short paragraphs say more about his life than a long essay might do. Mr. Sznejser also sings very well in Yiddish, which made the interview even more interesting.

My name is Mojsze Sznejser. I was born on 5th March 1920 in Lukow. My father was called Dawid Josef Sznejser. He was a cobbler. My mother's name was Szajndla Sznejser, her maiden name was Sosnowiec. I had two brothers and one sister. My brother was called Abram and my sister was called Chana. I was the oldest. Then came my brother and sister; the age difference was two years. My other brother died young, in the 1930s, as a child - Icek, his name was. We lived in Lukow, on Pilsudskiego Street, near the cinema, and in the apartment there Dad had a cobbler's workshop.

Ma's family came from Radzyn Podlaski. That's in Lublin province [a region in eastern Poland]. I remember my great-grandfather was called Awrejnu, and my great-grandmother Suwe Gitl. My grandfather was Bejro Lajb Sosnowiec, and my grandmother Rywke Laje. I don't know her maiden name. Granddad worked for a miller. He had a beard, like my great-grandfather, but not a long one, it was average. I used to go there, and I would sleep at Granddad's. I remember Granddad's house in Radzyn. After the war I came back to Poland and went to visit that place, Radzyn Podlaski. I remember, half the house was finished, and the other half was still unfinished up to the war. I came back in 1946, and other people were living there, a Polish family. I said to them, 'I haven't come to take it back, just to see what it looks like. I went back a second time, the same year, and it had all gone. Somebody had taken it down.

I didn't go to the synagogue with Granddad, because I went with Dad back home in Lukow, and Granddad went there, in Radzyn. I remember I went there once on a Saturday by bike, from Lukow to Radzyn, and that was a sin, so when Granddad asked me: 'Where were you?' I answered: 'I was here, sleeping at a friends' place.' I couldn't have told the truth, he'd have leathered me.

On Dad's side the family was from Lukow. Granddad, I remember, was called Szymen Sznejser, and his wife Pesech. I don't know her maiden name. Granddad was a cobbler too. They lived near the Polish elementary school, where they rented an apartment off this one Jew. It was this one room and a corridor. Granddad would sit working in the room where the beds were too, and there was a bit of a kitchen taken off that room. They weren't rich.

Dad had one brother and two sisters. His brother was called Sahje and he was a cobbler too. His wife was called Ruhla, her maiden name was Sobelman. They had three children, but I only remember the name of one son - Herszel. They lived in Lukow. One sister was called Gitla. She stayed with my grandparents; I don't know if she got married.

Dad's other sister was Zlata. She married Aaron Konski, a tailor. They had a lot of children: Mojsze, Szlojme, Szyje, Herszel, Chaim, Josel, Abrejmale and Chana. Eight children. At first they lived in Lukow, where one son - Szyje - was religious, wore sidelocks and went to the yeshivah. And then they moved to Warsaw, where my uncle got a job as a tailor for the army, and Szyje stopped being religious and started to work. In Warsaw they lived at 20 Twarda Street, I remember to this day. I had one more cousin, more distant family, related to Grandma on Dad's side, Mojsze Zilberman was his name. He was very big, tall. He worked as a tailor, was earning. When he came over when I was small, he would give me a zloty. 'Here you are, have a zloty,' he'd say - I remember that. They lived in Warsaw, at 50 Dzielna Street.

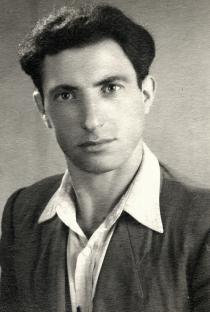

Ma had three sisters and four brothers. She was the oldest. Her sisters' names were Toba, Frajda and Liba, and her brothers, in order, Symche, Mendel, Chaim and Mojsze. And that uncle Symche, I've got a photo of him from before the war, well, he had a son. I remember that son - back before the war I slept in the same room as him in Radzyn. That son, Dawid - in Polish Tadek Sosnowiec [he didn't change his name, that was just what they called him if they used a Polish name] - after the war, he went to Warsaw, got married there and settled down. He died a few years ago, now only the young generation lives there. And Ma's youngest brother, Mojsze, well he's still alive, in America. He went to Israel after the war, changed his mind there and went to America. He had his own apartment, and left it. I didn't ask why.

Ma's sister Toba lived in Siedlce with her husband - Shulke Wyszkowski. I went to their place once; I was going home for Easter [Pesach] from Warsaw. I went in to him and said: 'I'm going home.' And he said: 'Wait!' He nipped out and bought something - 'Now off you go home.' He bought something so that I'd have something for the holidays at home. Ma's second sister, Frajda, lived in Siedlce too. Her husband, Mendl Zonszajn, was a painter. He painted stations as well. When he came to Lukow to paint the station, he lived with us on Pilsudskiego Street. That was when my father was already dead. He worked a while and then went back home.

There was Ma's more distant family too; they lived in Radzyn, not far from my grandparents. He was Ma's cousin, Icek Kopciak. He was a carter, he transported all types of goods, flour, grain, whatever people gave him, and he'd carry it all from Radzyn to Lukow and back. I knew his father and mother. The Kopciaks lived on the same square as my Ma's parents. It was this big square, not cobbled, on the edge of town. In the center of town there was a church and a rank for cars and out there on the edge a lot of Jews lived. And there was a prayer house there, on the same square.

My Ma was very pretty; I remember that she wore a sheitl - a wig. And she taught poor girls to dance. I don't know, I didn't see it, but people told me that she taught dancing. She didn't make anything from it, she taught her poor friends. That was back when I didn't exist yet. She was still a girl. After that she couldn't teach, because she had a family. And she helped Dad with his work: he taught her to repair galoshes and do heels. He had bad turns with his heart because of the stinking glue, so she repaired the shoes herself. Apart from that she kept house. She cooked well, ooh! Very well. She did everything just as it should be. Dad got his portion first of all, he had to. Yes, she could cook and bake. Everything was kosher.

On Thursdays everyone went to the mikveh, first women, and then men. There was a very big synagogue and special prayer houses. And the women went into the synagogue by a separate entrance and stood where the young people studied during the week. It was connected to the synagogue, and there were these special little open window holes, so that the women could hear the prayers and repeat them. There were other prayer houses too, smaller ones, and the Hasidim 1 had their own prayer house. There was a yeshivah as well, and a bes medresh. I remember the rabbi, too, he lived down by the river, in an upstairs apartment; I never went there. But I remember that people didn't like him. He made himself out to be the cleverest, you see, he wanted to prove that he was somebody, to rule everybody. That's why they didn't like him.

On Saturdays nobody worked. You weren't allowed to do anything, not even heat up water. If your candles burnt out, you didn't light them again. If people had electric lights, somebody else [a shabesgoy] came to switch them on. We had a kerosene lamp, and again, once it had burnt out, nobody lit it again until later on Saturday. Everything for Sabbath on Saturday was prepared on Friday. Ma made the cholent and took it down to the bakers', because their oven was hot all Friday. They put all the pots in it and then on Saturday they opened up the oven and it was all hot. They brought the cholent home and everyone ate. And when Father died it was hard; at Easter [Pesach] Ma would go out to make matzah to earn enough to keep us. And of course she was given matzah.

My father died when I was coming up 12, at the age of 42. I remember that he didn't have a beard, and on his head he had a hat, like the ones in the Russian army. He served in one of those armies, back when it was still the Tsar's army [see Partitions of Poland] 2. He was a good cobbler, all his customers were Poles. The workshop was through the courtyard at first, and later at the front, onto the street. Dad wasn't very religious, but Sabbath was observed. And when Dad went to the synagogue, he took me with him. I remember we always sat on the left.

I remember that before he died, Father went to the hospital; he had heart problems. And my mother dreamed that she was burying him. At the same time a friend had come to see my father and given him a bit of vodka to drink, and Father died in the hospital. And then that same friend came to our house; I remember we had this closed-off corridor, and well, he opened the door and took Father's sheepskin.

I hardly remember my sister Chana. I just have a photograph of her, nothing else. I remember that she learned to count and sew, because that was what she had to do. She had her friends, but I don't remember her having any toys, just these dolls made out of twisted rags. And after that I don't remember anything at all, the war was a different life, and that other life just went, was lost. My sister was still young. And when me and my brother escaped into the woods [early in the occupation], she stayed with Ma. And when we came back they weren't there any more.

I remember the holidays, Chanukkah and Purim. Once I dressed my brother up at Purim, and he had a saber, a real saber, and we went to our uncle's, Dad's brother, who we seldom went to see. It must have been after Dad died, because before that, when we were small, I don't remember us dressing up. And at Pesach Ma did everything herself at home, baked challot, cooked noodles. There were separate plates and mugs for Pesach, and if there weren't enough, then they had to be cleaned. I still have separate plates, like we did back then at home.

At home we spoke Yiddish. But I could speak Polish as well. I went to elementary school, but only until my dad died, then that was the end of it. I couldn't go to school any more because I had to go out to work. And after that I only attended evening classes. But I remember the teacher at the elementary school, Miss Cetnarska: she taught Polish, sums, everything. And there was another elementary school, where only Jews went, but the teachers were Polish. I went there for religious studies. Once a week they had Jewish religious studies there. I went to cheder as well, and then to talmud torah. Our lessons were in Hebrew. We learnt to pray and translate into Hebrew. We were taught by Josel the baker, and then by Awrum Zyto, who came from Israel [Palestine at that time], and taught us Hebrew. The cheder was private, I remember, at old Nissenbaum's home, who taught us. The talmud torah was in a big room connected to the synagogue. You had to pay for it all; Dad was poor, but we had to pay anyway.

Lukow was a very pretty town. There were two churches, two grammar schools, the 22nd Riflemen's Regiment [a unit of the army of the Second Polish Republic]. It was a lovely life! And Lukow was bigger than Radzyn. In Radzyn you had to walk nine kilometers to the [train] station, but in Lukow there were two stations, one for Lublin and one for Warsaw. I often went to Radzyn by bus to visit my grandparents. Ma would go to the driver and tell him to throw me off in Radzyn by the church.

There were different youth organizations in Lukow: Shomers [see Hashomer Hatzair in Poland] 3, halutzim, Shomeradats [Hashomer Hadati], Zionists, but no one in my family was interested in that. They had their own work. I sometimes went to Zionist meetings, but we didn't get out much, because there wasn't time. We had to work.

There were a lot of Jews in Lukow before the war. They had bakeries, and there was a Jewish slaughterhouse. The Jewish slaughterhouse was in this big building near the river. There were two slaughterhouses in the building: the Polish one and the Jewish one. The Polish part was closer to the river. But the slaughterhouses were separate: separate entrances and exits. If they did something wrong with the meat in the Jewish part and it wasn't kosher, they would give it to the Poles. And then they settled up with money. But normally everything had to be kosher. And on the right side the Poles slaughtered pigs and other [non kosher] animals. And all the blood flowed down into the river.

In Lukow, before the war, there were different sorts of Jews, like in every nation. I remember one Jew was killed by some other Jews. Why did they kill him? Because he split on some others. He was called Jojne Bocian, he was a party bloke - a communist. And once, the Polish police caught a few communists and put them inside, and Bocian was among them [during the Second Polish Republic, in the 1930s, the activities of communist parties and organizations were illegal]. Well, one of the policemen went to a tailor to have something done, and the tailor was Bocian's brother-in-law, Sliwka, his name was. This tailor asked him why they'd arrested Bocian, and if they could let him out. The policeman said that they could let him out, but on one condition: he wanted him to denounce the others. Bocian agreed and they let him out.

Bocian went to the [communist] organization and said that they had to have a meeting. He wanted the police to catch them. But the other people weren't stupid. They were surprised that he had been let out, while the others were still inside, and they worked it all out. They arranged a meeting somewhere in a field and sent someone to watch the site. And one of them was there and saw the police come but that Bocian wasn't there and the others weren't there either. And then when Bocian asked why they hadn't had the meeting, they said that they were going to have it another time. And Bocian told the police again. When he was sitting with his parents and his brother-in-law at dinner on a Friday evening, this guy from the party came to him and told him he had to go to Siedlce to do something. Bocian went by train. In Siedlce there was this guy standing in a doorway, and he told him to come up to him for instructions. Bocian went into the entranceway, and the other guy killed him. The next day his mother screamed: 'Help! They've killed my son!'

There were rich Jews too. Gasman, for instance, who was a cobbler, had a large firm, other cobblers working for him, and who built a big house. I didn't work for him, because the firm wasn't around any more in my day, but people used to talk about it. I just saw the house, this very big house. There were other rich Jews, mostly bakers. I remember there was one who lived near the bridge; he had a very big apartment. And when the kids were walking to school, whoever they were, Polish or Jewish, and stood in front of the window looking in, the baker would call them and give them a roll. 'I haven't got any money,' the child would say, but he just said: 'Eat up, eat up, your Ma will pay.' And whether or not she paid, he would give out the rolls either way. And his brother, Josel the baker, he was a teacher, and taught us Hebrew.

Life with the Poles was harmonious enough. We lived with them like brothers. They'd come to us, so we'd go to them, you had to. When my father died, the neighbors would come round to my mother and say: 'Neighbor, why don't you come round for some potatoes?' I still remember those neighbors' names: Chajkowski, Golaszewski. And when a Polish funeral was passing the Jews paid their respects too, and took off their caps. We didn't wear kippot on the street, you see, but caps or hats. But later on, when I was working and just going to evening classes, there were times when youths were out to beat us up, throw stones at us [in the late 1930s anti-Semitic feeling in the Second Polish Republic intensified]. The teachers didn't let us out then, so that they wouldn't throw stones at us.

It was only Poles that came to us with work - farmers, teachers. And when Dad made some shoes for this one Pole and Ma took them round, she took me with her, and when I got there I had to kiss his hand out of respect. And I'll tell you what else I heard, what they used to say: that back in the time of the Tsar there was this old Pole with a beard, Kaminski, who had 18 children. Well, when the Ukrainians wanted to throw the rabbi out of the window, he wouldn't let them throw him off the balcony. Well, I heard that when he died all the Jews went to the funeral.

The Kaminskis owned the cinema and the library, they were very rich. We rented our apartment off Kaminski's son. That son, Mietek, his name was, he had a bit of a limp. He was into stuffing birds and other animals. He wanted to take me hunting, but my mother told me not to go, because if I ran around I could get killed by a stray bullet. That Mietek rented apartments to lots of Jews, and if anyone couldn't pay, he didn't throw them out, he would just tell them to sweep the street a bit. Mietek's wife was the daughter of a chimney sweep, and very nice. They had two children. I used to go round to their house every day. Sometimes they'd send me out for something. Their children were younger than me, but I got on with them. Those were very good people.

I remember one other thing that happened, that was on Pilsudskiego Street too, the cinema was there and the club was there. This Jew, a dancer, was walking by the club, it was a Saturday, and he was going to the club, not to the synagogue. And another Jew, with a beard, was going to the synagogue, and two Polish army officers grabbed him. One grabbed the Jew by his beard and pulled it. And the dancer, oh he could fight, I saw what he did - when he head butted the one of them, the other officer ran away.

I remember that where we played there weren't any Polish children. We played ball [football] mostly. We played in a field, and the farmer would come and chase us away. Because he had sowed it and we were getting in the way and wrecking the field. There were a lot of children in Lukow. There was this one Jewish kid in Lukow, who went to the grammar school, an only child, the son of a rich painter. Well, he had those wheels on shoes [roller-skates]. The only one in Lukow! And I remember I used to go to the cinema, because my brother helped out at the cinema. One guy would let us in, and we'd sit there quiet as mice. Good films and all sorts there were. They'd screen banned ones, but I went anyway.

My grandparents and parents didn't go on vacation, but I remember that rich Jews did. Poles would let out their homes, sometimes even moving into the barn, because they were paid. There were places like that in the woods, three kilometers or so from the town. I didn't go away anywhere, just to family in Warsaw, Siedlce and Radzyn Podlaski.

After my father died I had to work. First I worked for this one master [cobbler]. I wanted him to give me another zloty, he wouldn't, so I moved on. To Mojsze Onikman. I worked there and my brother did too. I've got a photograph of us working together, with one other guy - Lajbele Bomstein. That Lajbele was denounced to the Germans by his own father! Lajbele met a girl somewhere; she was escaping and hiding from the Germans. Lajbele found a Pole and hid the girl with him, threatening to kill him if anything happened to the girl. Later on he hid there too, and some other people as well. His father found out where he was and split on them all. They killed the whole family and all the people hiding there. A father split on his own son!

After that - this must have been in 1936 - I came to Warsaw, to my uncle [Aaron Konski]. I remember he said: 'There's so many hungry mouths around here there'll be enough for another one!' And off he went. Went off there and then, and found me a job. I stayed there until the war. Ma, my sister and my brother knew where I was, because I'd left home to earn some money. I lived with my uncle, at 20 Twarda Street. We lads all slept in one big room, my uncle and aunt and their daughter in the other. There was this bed, big enough for five people. And in the workshop was the kitchen and my aunt made dinner there and she'd argue with me for not coming in for dinner. My uncle was a tailor for the army and once, I remember, Edziu the neighbor came round, a Pole, and wanted to learn to be a tailor. And my uncle asked his mother: 'Do you agree? Edziu wants to be a tailor.' And she says: 'Yes.' 'Well then, so be it,' said my uncle, and from then on Edziu got dinner. And later on, that Edziu came to my cousin's funeral; I was there too.

When I lived in Warsaw I didn't have any contact with the Jewish community, I didn't go to the synagogue, just straight home from work. We didn't work on Saturdays, so I would go to these unofficial beaches to swim [on the bank of the Vistula], and the police would chase us. That was in Praga [a district of Warsaw]: young people, students used to meet up there, on Zamenhofa Street. I worked first of all on Panska Street - my uncle got me the job - then at 49 Mila Street, and then at 12 Zamenhofa Street, by the passage - there was this passage there to the other side [of the street]. And the youths used to meet at 26 Zamenhofa, all our youths [Jews]. There was this spot there, where people would meet, talk about this and that, just young people. That was a to-do, it was great.

I went back home right before the war. In 1939, in September or October, I and my brother Abram escaped into the woods. It wasn't easy, you had to hunt for food, and keep your wits about you, and you had to be careful with other people in the woods too. After that we slipped over to Brest [see Annexation of Eastern Poland] 4. In Brest it was a bit different. In Brest they did a round-up and shipped me off to Belarus, to Gomel, and there I worked in a factory, Selmasz. It had belonged to a Jew, that factory. I did whatever work they gave me to do there: I worked the thresher, the chaff. I lived with this family in a Jewish woman's house. I asked the foreman to give us some coal to burn. They gave us fuel, but she burnt it for herself and not for us in our apartment, so I got out of there right then.

By then the Germans were rounding people up [in June 1941 Germany attacked the USSR], and I escaped by train to Kurgan, out there it was Russian. There I worked as a cobbler. I wasn't in uniform back then. Later on the Russkis [Russians] were scouting for the army and they sent me to Chelyabinsk, to an aluminum factory. That was when I got separated from my brother, who got sent elsewhere. In Chelyabinsk I worked on a building site. And I said to the foreman: 'I'm a cobbler.' So he said: 'Go and get your tools, you can repair shoes.' But I didn't understand Russki [the Russian language], didn't understand that you had to get a permit to leave, so I got on a train to Kurgan and off I went. I don't remember where they caught me, it might have been Alma Ata or somewhere else, but they hauled me off the train and they were telling me I had escaped from the army. And after that they ferried me around, I can't remember where the court was, somewhere in Russia. I didn't understand anything, they were all speaking Russian. I got the death penalty, that's all I understood. But just afterwards they kept me in prison - I don't remember where or how long. Later they changed my sentence to ten years' labor - I'd learnt a bit of Russian, so I understood that.

When they'd changed my sentence they shipped me out to Nizhniy Tagil, to a camp, and turned me out into the middle of nowhere. Starved as a dog I was. Frozen hands. I even slept in my clothes, had nowhere to lay my head. After that they built barracks and we slept in our clothes there too, as they didn't heat them. One camp commandant came out from Moscow and gave an order that they were to hand out mattresses. Once I started working there, this naradchik [Russian term for an official in a labor camp] came along and said: 'You're going to Moscow. You're going to work and from there you can get home.' He was a Jew, he was in the camps too, but he was a naradchik.

And I went to Moscow. In Moscow I worked in a camp, as a cobbler. They brought work down from the Kremlin and then sent it off to the front. We were mending shoes. About 30, 40 people worked there. I was strong then, always got what I wanted. Once, it was a Sunday, I remember, we went to the kitchen to eat. I sat down, and opposite me Ivan Gadzhuk [another prisoner] wanted to sit. He could have sat down, there was space, but he wanted to sit where somebody else from the gang was already sitting, an older guy. And he [Gadzhuk] was a strapping guy. And Gadzhuk tells the old man to get up and make room for him. The old guy, like old people do, got up slowly, Gadzhuk pulled the bench out, and the old guy didn't make it, and he fell over. So I say to Gadzhuk, 'Ivan, happy now? Do you have any honor?' And he starts insulting me. Then he grabbed the bench, pulled a leg off it and threw it at me. I picked the leg up, went over to Ivan, and gave it to him on the head, grounded him and kicked him all I could. He had his boys, but none of them came over because they knew I was right.

That night I was afraid to sleep, because Gadzhuk could have come. So I put a cupboard up [against the door] and I had this big knife. I slept all night and in the morning we went to work. The women working in the office went to the director and told him everything, that Mishka, that's me, had a brawl with Gadzhuk. The director came to me then and asked whether I couldn't have sorted it so that Gadzhuk wouldn't come to work any more at all. That's what the director said!

All of us in that plant had to make quotas [quantity of work performed in relation to the average per employee according to a plan imposed from above]. And I made the biggest quotas and that saved me. 400 percent, 450 percent I could do, day in, day out, and I had a good reputation. They set store by those quotas. That reputation saved me. There was an amnesty for the Russians, and I got counted as one of them. They'd read in my papers that my town was Lukow, see, and out there near Moscow was Wielkie Luki, and I came home as a Russian. That was in 1946.

Practically all my family was killed in the war. I don't even know which year my Ma and my sister died. My brother Abram survived: he was in Russia too, and then in Romania. There he met his future wife, a Romanian Jewess. Straight after the war they went back to Russia together. From Uncle Konski's family everyone was killed, only one was left - my cousin Szlojme, or Stanislaw Konski. They died in Warsaw; I don't know how he came to survive. He'd have told me, but I didn't ask. Back in Brest [in 1939], I met that other cousin of mine, Zilberman. He said: 'I've got to go back to Ma, because I left her behind.' He went back to his mother and he died too; they died together. Her name was Sonia. From Ma's family they all died except Uncle Mojsze Sosnowiec. He lived the war out in Russia as well.

When I went back to Lukow I remember that some people came round asking if I wanted to help take ours [the corpses of Jews] out of the Catholic cemetery. I went to the grave, opened it up, and we dug out three men and two women, and took them to our cemetery. And this Pole, Mr. Cholocki, when he met me, he gave me a photograph of the Germans finishing off Jews wearing prayer shawls. He'd hidden to take the photograph, sat up in a tree. He gave it to me, didn't want anything for it. I gave it to some other Jews who were emigrating. 'Here you go,' I said, 'this'll come in handy abroad.' I met the church organist in Lukow too, Schiller. He said to me: 'Give us a hug! Come here, I'll tell you everything. The Germans came round to his father during the occupation and said: 'You're coming to work with us.' And he shook his head: 'No!' So they killed him on the spot - him, a German himself. He would always grab me by the ear. There are all sorts of people in every nation. I can't forget that Schiller, he knew me, see.

When I got back to Lukow I started working straight off. They gave me somewhere to live; I had a place to lay my head. And I'd still be there, in Lukow, to this day if it weren't for this one Jew, who took me in. Borrowed a few coins off me and said: 'Come on, we'll go West.' And off he went, first of all to Warsaw. I chucked everything and went after him, first to Warsaw, and then he says: 'How can I go anywhere - the wife ill, the kids ill.' I could have stayed there at his place, but I didn't want to, he'd already had me once. And I went off to Dzierzoniow. And that rogue came to Dzierzoniow from Warsaw to sell things. He brought some chocolate. And I took my money back then. You see, he asks me if I want to buy some chocolate, so I say yes, that he should leave it, and I'll pay him when he comes back. And that's what he did, left some chocolate and went off. Then he came back and wanted his money. So I said to him, 'You only took me in once, I'm not being had again!' Because he had borrowed some money off me and not given it back to me. He thought I'd forgotten. But I outwitted him.

I went to Dzierzoniow with my wife, Chaja, nee Sznajser. I'm Sznejser and she's Sznajser -that was a laugh. We came back from Russia to Lukow together, and then went to Dzierzoniow, where our first son, Dawid Berek, was born on 10th February 1947. Well, I worked in a co-operative there, as a cobbler, and Uncle Mojsze came to see me, my mother's youngest brother. During the war he'd been in Russia too, and then he lived with his wife and children in Legnica. And he took me to Legnica. There, in Legnica, Chaja and I got married, got all the papers. We just put our names down in the municipal council. We went, we and our witnesses, and that was all. We didn't have a wedding in the community before the rabbi; at the time no one went to the community. I saw weddings like that before the war, under the chuppah, and with all the family. My uncle Mojsze Sosnowiec had a wedding like that, only I can't remember where.

I worked for that uncle of mine, he was a cobbler too. My uncle gave us somewhere to sleep, a tiny place, just me and the wife there, and the oldest boy, he was just a baby then, in a pram, a few months old, see. And then I found an apartment and it was all right. After we had two more kids: my son Szama was born in 1950, and my daughter Syma in 1952.

After the war my brother Abram came to stay with us in Legnica, with his wife. At first they lived with us, I gave him a separate room, and later he found another room and went to live there. Two years he was here and then he went to Israel. I never thought of going there. I wanted to stay here. This is my country.

After the war there were a lot of Jews here in Legnica. The synagogue was on Chojnowska Street. I used to go to the synagogue on the holidays. I didn't go on Sabbath. There were lots of people, see, and sometimes I was at work. Now on Saturdays I go to the synagogue, well, got to help keep the ten up [the minyan]. I know how to pray: I've got my prayer shawl here too, and I put it on, but not all of it, because I've forgotten it now. Back then there were lots of people. There was a synagogue and a SCSPJ club [see Social and Cultural Society of Polish Jews] 5. I went to both. I always went to the SCSPJ on an evening: we'd come, play dominoes, and there was a buffet bar. Life was different - lively; we'd go to the club, to the park, once in a while to the cinema. The club was on Nowy Swiat Street. You could go every day of the week. They'd have an act come in and play; there was a Jewish theatre. The theatre was on Nowy Swiat Street as well. They'd come from Warsaw, from Wroclaw; the shows were in Yiddish. There were Poles that sang in Yiddish there too. One time they came up from Wroclaw, and I said: 'Listen up, I'll sing you a song, but without the piano, so everyone can hear.' And I sang for them, and they clapped.

On the holidays they would organize something in the synagogue, but it was the same folk who came here to the club. And there were Jews who didn't go to either, didn't want to let on that they were Jews. But I went to the club from the beginning; I never thought of letting it go. You can't change what you are. A man who changes is a good-for-nothing. Because he'll change all the time. But I will always be who I am, what's the point of going round lying? I can't, that's my nature. My kids are the same. My oldest son was called Dawid Berek, after my father and my granddad from Radzyn, and my second son Szama, after my other granddad - Szymen, and my daughter Syma too.

Here in Legnica everyone always knew, and still does, that I'm a Jew. I've never really had any problems. On Kartuska Street, where my workshop is, everyone knows me well. I tell them, 'That's who I am, and I'm not going to change.' People who know me call out to me from a long way off. There's this one Pole who's been going mushrooming in the woods with me for 40 years. 40 years, and he won't go with anyone else, only me! It was he who taught me to pick mushrooms. Like a brother, he is; once I needed him to go for my daughter to Swinoujscie [a Polish Baltic port], because she was coming back from Denmark, so I ask him if he'll go, and all he asks is when. I told him 'today', so he got straight in [his car] and went. He's known me so many years and to this day he comes into my shop every day. He came to have his shoes mended once and we got talking. And it's 40 years now.

I belonged to the party [the Polish United Workers' Party] 6, but I never sold anyone. My boss said: 'You have to inform.' But I said no. He didn't really want me to, see, he just wanted to know what kind of a guy he was dealing with.

Later on I worked in a Jewish co-operative, it was called Dobrobyt [Prosperity], my uncle worked there too. It was a Jewish co-operative but there were Poles working there as well: cobblers and boot-makers, they made bags there too. Then they changed the name to 'Kilinskiego'. I worked there until 1960, until Gomulka closed it down. My uncle handed in his notice and went abroad: first to Israel, and from there to America. But in 1960 I opened my own place and I sat and made shoes.

In 1968 I remember that it wasn't much fun when all that fuss reached us in Legnica. It was just Gomulka's work [see Gomulka Campaign] 7. Well, not his on his own, but the organization [the Polish communist party, PZPR], but he made the most noise: 'All the Moszkes [Moses] to their dayyan!' And I sent my children away. I said to them, 'What can you do? Go.' I thought that they would have a new place there, that perhaps they'd make a place for us. My son Szama went to Israel and my daughter Syma to Denmark. I thought that one day the wife and I would go to live with one of them.

In Israel Szama went straight into the army. Almost straight away he was injured and went to stay with family, my mother's cousin, Icek Kopciak. (The Kopciaks had left for Israel earlier, and before they left they had lived in Legnica too. Icek worked in a co-operative, Model, where they made hats). But there in Israel Szama didn't want to stay with them. One day Kopciak's wife put some food out and he ate a lot. Szama was very ill, but he didn't say anything to her. And she went to her husband, who was in the garden, and told him that Szama had eaten a lot. And the window was open and he heard. And right away he wrote to me, 'Dad, I'm not going there again.' And after that I didn't have any more news from him. I just found out in a letter that he had died, and that he had left a few zloty. Well, I could at least have written back and told them to put up a headstone in the cemetery, but I didn't think, and I didn't do anything.

Syma got married in Denmark and her married name was Gertner. She was in contact with the Jewish community there. She lived with her husband and her mother-in-law. I went to stay with them. The mother-in-law was a Russian Jewess, not a very nice woman. When my daughter put food in front of me she looked kind of oddly. And then in 1993 my daughter died too. She's buried in Denmark in a Jewish cemetery.

I stayed in Legnica with Dawid, my eldest son. He didn't want to leave, because he didn't want to leave me. My wife died in 1986, right after the disaster in Russia [the April 1986 disaster at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the Ukraine]. She went out early in the morning, breathed in the air and that was it, at once. She died shortly afterwards. My son married here in Legnica. But then he threw his wife out. Because she told me that when she's in the kitchen she didn't want to see me. In my house! So Dawid threw her out. And they had a child, a son, Mariusz is his name. She taught him to be against his father. When Dawid wanted to talk to his son, he would run away. Then, when he got married, he didn't invite his father, and when they had a baby they didn't invite him either. It's only now that I'm in touch with him: he comes round from time to time, at last, after 35 years I'm a grandfather to him! All that was hard for Dawid. And he paid child support money for 18 years. In the end he died too, in 2002. I prayed for him for a whole year, recited the Kaddish. I've given my grandson a lot of things his father left, because Dawid was always buying things for him, even though he couldn't talk to him.

I carried on working. And I still work to this day, you have to live a normal life, see. And I miss Lukow, my town, life was good there. Not long ago this guy came in with a pair of shoes to repair. And he asks me whether I'm not from Lukow. Someone had recommended me, someone from those parts. He gave me the work. Other than that there's no work, but you want to chat. Sit and wait to die? You have to keep going.

Glossary: