Panni Koltai

Budapest

Hungary

Interviewer: Eszter Andor

Date of interview: May 2003

Panni Koltai lives in a green residential area of Budapest, not far from the center. She lives alone in a comfortable two-bedroom apartment furnished with 1970s furniture, but her son and grandsons visit her regularly. Panni is a lively and ironic old lady. I sat with her half a dozen times, however, because she got tired of talking for too long. She told me colorful stories of her family and her prewar life, but she was not very interested in talking about her life after World War II. Her grandson Andris is very interested in the family history and the interview was in fact made on his initiative.

Family background

Growing up

During the war

Post war

Glossary

My grandparents on my mother's side come from the Pollak family. They were these so-called Polishi Jews, Polish Jews. My grandfather was called Jakab Pollak. He was born in Gyongyos in 1839. My grandmother Julia Pollak, nee Gajdusek, was born in Verpelet in 1848. This was a big family. Mom had known some relatives but I didn't know any - money divided us. Grandmother's relatives, God knows, maybe they only had a few dimes more than us, but they looked down on us, the poor relatives.

The Pollak grandparents also lived in Eger like us. They lived in a typical Jewish building. There was a big, shabby apartment building by the stream, and many Jews, different types of Jews, but mostly poor Jews lived there. I had many friends from there. Grandfather Pollak was a haberdasher, as they called it back then, so he traded in dry goods. He started trading and going to fairs when he first came to Hungary, so the Pollak relatives were a line of merchants. He met his wife Julia here, I guess, but even my mother didn't know anything about this. They weren't rich, but they had many children. At that time it wasn't so uncommon to have seven children. So what if they had seven children? They would raise them! When the Eger stream burst its banks, my grandfather was ruined, the goods he had - and he didn't have much, because, as I said, he went to fairs and traded - were ruined in the water. And he was completely broke.

I remember my grandmother; as far as I remember, my grandfather wasn't alive any more when I was small, but I have a photo of him. He had a beard, but he didn't have payes. They weren't bigoted, despite the fact that they were Polishi. Grandmother always wore a wig, even at home. And she was bald under her sheitl. I don't know if she had a special wig for the holidays but I'm pretty sure she did. She must have had one because they were very fussy about these things. My mother didn't wear a sheitl. She kept her hair after she got married. She had nice ginger hair; she was a very beautiful woman.

My mom, Aranka Friedmann, nee Pollak, was born in Eger in 1887. She must have finished elementary school but I don't know how many classes of it. Mom had five brothers and one sister: Uncle Lipu, Maxi, Naci, Mendel and Hermann and Aunt Szeren. She had another seven siblings but they died in their infancy.

Her sister Szeren Hirsch, nee Polak, lived in Kal. Aunt Szeren made a living by buying up geese; she killed them and brought them to Eger every weekend and we sold them. They must have been kosher geese because we sold them to Jews. Mom helped Szeren, so we always had a goose left for ourselves and Mom cooked all sorts of stuff from it - I don't remember what - for the week ahead. I don't remember Aunt Szeren's husband, he had already died by that time. Aunt Szeren had a daughter called Olga and a stepdaughter who got into our family somehow.

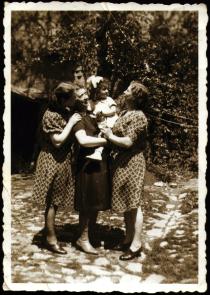

We used to go on holiday to Kal. It was a very interesting village, very sandy, full of fine warm sand, and we used to go around barefoot. I loved going there. My sister Piri used to go there regularly because Olga and her cousin Iren [Uncle Lipu's daughter] were about the same age as she. We got together every summer. Family members were much closer to one another than what we can imagine today. Back in those days, these relationships were important.

Aunt Szeren was deported. The last week before the Germans occupied Hungary I went to visit my parents, and Olga was also going home, and we ran into each other in the train. I was already married by then and so was she, and we were very happy to see each other. But we were very sad because we had a kind of premonition that something very bad was going to happen. It was so horrible to feel already back then that there was no escape. We knew it.

Uncle Lipu was born in 1867. He was quite wealthy. There was a haberdashery in Eger, the biggest Jewish business, which was Uncle Lipu's. Uncle Lipu looked almost like anyone else in the Pollak family - they all had round Jewish faces. But he was blond and one could see that he had longer payes. The Pollaks were all ginger-haired. And we all inherited this, we were all blond, my sisters and I. Uncle Lipu had a beard, they [the male members of the Pollak family] made sure that they all wore a beard. He also had a hat but the Pollaks didn't display their religiosity so much in their appearance. They really observed all the religious precepts. There had always been some disagreement between Uncle Lipu's and our family because Dad was a more modern Hungarian Jew. My father also had a mustache [like his father], and he paid special attention to twirling it; he was a very meticulous man. He dressed in typical Hungarian clothes as well. His shoes were always shining. So, he put great emphasis on his appearance. Uncle Lipu died of a natural death in Eger before the war.

Uncle Maxi lived in a small village called Borsodszemere. He married a woman from there, called Giza. They were merchants; they opened a little store. We rarely visited them. We didn't like going there. Aunt Giza didn't give us food when we visited them. My sister Piri was really funny once because they put a watermelon under the bed when they were there on a visit to make sure that they had something to eat. It wasn't Aunt Giza who gave them the watermelon, they just took it. Aunt Giza had three daughters, two of them were still alive not so long ago, living in South-America. Maxi and Giza both survived the war. They had been deported to Auschwitz. They left for Australia after the war.

Uncle Mendel died young of some disease. I didn't know him, Mom only mentioned him. There was something messy about this Mendel; they didn't really talk about him in the family. Maybe they were hiding something about him from us.

Uncle Herman lived in Pest [Budapest], he had a remnants and oddments store, a haberdashery, on Kiraly Street. We always received very nice fabrics from him and made beautiful dresses out of them. He gave us fabrics for free and we also bought some from him. He had two sons, Pista and Laci, one was a lawyer and the other a merchant, he remained in his father's business. I don't know if they were deported during the war or if they had died before.

We weren't as close to them as to Uncle Naci in Eger. His family came to see us very often because we lived next door to each other. And we loved Uncle Naci's family; they were very nice people. In fact, we were the closest to them from all of Mom's relatives. Uncle Naci owned a glassware shop in Eger. He had a son, Gyuri, who worked for MASPED [Hungarian state- owned forwarding agency]. Gyuri and his family were very nice people; his wife is still alive. Gyuri was charming. He had a good job and he was good at it. And he spoke several languages, including French and English, I think.

My Pollak relatives had a very good sense of humor. And Uncle Naci picked on Uncle Lipu's family whenever he had a chance to do so. Once one of Uncle Lipu's sons took the train together with Uncle Maxi, and the poorer one didn't have a ticket, and when the conductor came, he asked where his ticket was. Uncle Maxi said, 'My secretary will pay for it now'. And Uncle Lipu's son was so embarrassed that he didn't know what to do. He took out his wallet and paid for the ticket out of sheer embarrassment. The conductor left. 'Why did you say that I had money?' 'Because I didn't have a red cent.' Uncle Maxi was like this. There were some great anecdotes, which were always quoted in the family.

The Friedmann line came from Heves County. My grandfather, Samuel Friedmann came from Varaszo, where he was born in 1845. He lived in Recsk, and he had a tavern and a butcher's shop there. I can't tell you whether it was kosher or not. As far as I remember, they slaughtered the animals and sold them. Recsk is a small village near Paradsasvar. There weren't many Jews there. But there was a synagogue there; there were synagogues back then, even in smaller places.

I knew my paternal grandfather very well. He was more like a 'peasant Jew'. He had boots and a peasant hat, in one word, he dressed in an up-country way. Grandfather had a very handsome mustache. He didn't have a beard; he didn't care about the outward signs of religion. The villagers called him Uncle Samu, and loved him dearly. He had many friends, who liked him very much. They didn't cheat on people, they were honest [straightforward merchants]. In the village he had Jewish and non-Jewish friends, but mostly Jewish because they used to get together in the synagogue.

My grandfather had three wives. There were several grandmothers in every family at that time because women died of childbed fever or pneumonia or of some other illness for which we have medication now but which was incurable in those days. My grandfather couldn't afford not to have a wife because someone had to look after the children. I don't know exactly how many children my grandfather had, probably two or three from each wife.

My father's mother was called Pepi Friedmann, nee Flaschner. She was born in Erdokovesd in 1851 and she died in 1882. She was my grandfather's first wife. I didn't know her. My grandfather's third wife was Terez Hermann, whom we called Aunt Rezi and I knew her as my grandmother. And we regarded her as our real grandmother because they lived together for many years.

Looking back I can see now that my grandmother wore typical Hungarian clothes. She wore dresses that any rural peasant woman could have worn: several skirts on top of one another and blouses. She wasn't really very different from the other rural peasant women. There were certain customs in which she was different from them, but I couldn't really tell what these were because I was only a child then and didn't really pay attention to these things.

They weren't so strictly religious there in Recsk. The Pollak line wore sheitls, they were more religious; the Friedmann line wasn't that religious. They observed all the Jewish holidays; all Jews kept all the holidays in those days. It was unthinkable for them not to observe the holidays. But some people observed them more to the letter than others. I don't know how about their life there; I was only a small child at the time.

In those days some people owned a house, others only rented one. My grandfather had his own house. The tavern belonged to the house. It was a two-bedroom house, a proper brick house. So they couldn't have been too poor. In most apartments there was a children's room. All the children lived there; it didn't matter how many boys and girls a family had. And the parents usually had their own room. We lived like this and the Friedmann line did so as well. My grandparents heated the house with wood and coal, and they used a kerosene lamp. When I moved to Cece [in 1937] we still used a kerosene lamp there.

Both my grandfather and my grandmother were very hard-working people - she kept herself busy with the rolling-pin [that is, with the housekeeping]. My grandmother didn't help in the tavern; my grandfather probably had some employees. But I don't know much about these things because I had never there when they still had the tavern. Then they moved to Balassagyarmat in the 1920s. They sold the house and the tavern. One of my grandfather's daughters, Aunt Helen, had married a man called Sandor Klein and they took the old couple to live with them. Aunt Helen's husband, Uncle Sandor, was a master tailor and he had a workshop, and they had three children. My grandparents died in Balassagyarmat. My grandfather died in 1933 and my grandmother a year later.

All my sisters and cousins, including the three Korosi boys [my father's sister Julia's sons], used to go on holiday to my grandparents. And they always played very naughty tricks on my grandfather and grandmother. For example, they would pick up some mud and throw it at the wall when my grandmother had just finished to paint it nicely - because the walls were whitewashed there every week to make them nice and white. Grandmother came with the scrub and gave us a good thrashing, of course. I wasn't so much involved in this, as I was the youngest child. My sister Piri was past- master in this, along with the Korosi boys, who were older and knew how to provoke Grandmother.

There was an earthquake once in Eger. I can't remember exactly which year it was, but I was still a kid. My eldest sister was going to go to the office on a Saturday morning and the steeple on the market place was bent. It was such a big earthquake that the newspapers abroad reported that Eger had been completely destroyed. The Korosi boys, the three sons of my poor Aunt Julia - who were at university abroad - read in the newspapers that Eger had been destroyed. But it wasn't true at all, it was only that the journalists blew it up out of all proportions.

My grandfather came to visit us in Eger and was staying with us at that time and he was about to get up - it was a Saturday morning, Mom was cutting the milk loaf because she always baked milk loaf filled with chocolate. My grandfather was about to put on his boots and I can still see it in my mind how he wanted to lean against the bed but couldn't because the whole apartment was swaying. Dad ran out of his workshop and shouted, 'Come out with the children at once, there's an earthquake'. I don't know how he knew what it was because there had never been an earthquake anywhere near before. We children had the jitters, so much so, that we slept in the same room with Mom and Dad that night. We didn't dare go into the other room, although we would have been safer there, but nobody explained this to us.

Dad had one full sister, Aunt Julia or Juli, the mother of the Korosi boys. I think that Dad's sister married a man from Miskolc and moved there from Recsk. She was already a widow when she moved to Eger. She was a servant, she kept house for someone. There was a cheap kitchen in Eger, it was called dime kitchen, which was maintained by the Jewish community and she worked there. But for the most part we supported the poor woman, as much as we could. Aunt Juli died in 1940.

Aunt Juli was a poor woman and her sons paid for their tuition themselves. All three of them became educated men. Bela became a lawyer. He courted my sister Piri; it was customary at the time for someone to marry his cousin. Bela went to South America and settled in Buenos Aires. He had participated in the Hungarian Soviet Republic 1 and he had to flee later. He was hiding in Eger and before he fled from Hungary he came to say goodbye to us. I remember that he grabbed me and gave me a kiss, and his face was so prickly that I started shrieking and kicking. I was sorry for this later because I realized after he was gone that I would never see him again. But I did see him one more time, when he came home on a visit. He had married there and had a son there, but I don't know anything about him.

The second Korosi boy, Jozsi, became an engineer. His wife, Klari, was a Jew from a very religious family in Upper Hungary 2. They ended up in the Soviet Union for some reason. He was arrested there and taken to Siberia, I think, and he perished there. His wife and son repatriated in 1956.

The third son, Sanyi, was an ear, nose and throat specialist. He graduated from university in Vienna because there was the numerus clausus in Hungary 3 at the time. Sanyi first went to Shanghai, China, where he found refuge during the war. He married a Russian woman there. Later they moved to Cleveland, USA. He stayed there and he came to visit after the war. He had a son and a daughter. We were in contact with Sanyi. He was a splendid person, a good fellow; all three Korosi boys were very clever people. Poor Aunt Juli couldn't enjoy much of her sons, it grieved her that she couldn't be with them.

Uncle Lajos was my father's half-brother. He lived in Recsk. He was also a tailor by profession. And Dad gave him money so that he could leave Hungary during the war [World War I] as Uncle Lajos was supposed to join up, but he didn't want to and he went to America with Dad's help. And they agreed that once Lajos was settled there, Dad would follow him. But Dad got married in the meantime and then said, 'I already have kids, I'm not going anywhere, I'm fine where I am'. He never liked to change things, he was bound to one place, he had the mentality of the poor. He didn't want to become a somebody, he just wanted to work.

Uncle Lajos went to Cleveland. There were lots of Hungarians there already back then. He married a Hungarian woman called Malvin there. They had a daughter called Irenke Friedmann. Uncle Lajos had a stain removing workshop and Aunt Malvin helped him in the workshop. They never sent the family a red cent. Once a man sent by Uncle Lajos came to us. He popped into the workshop and said, 'Your brother sent you...' And my father finished the sentence: 'I know, and it got lost, that's what you were going to say, isn't it?' 'Yes, but how did you know?' 'I just know.' And it was as Dad had predicted it; whatever they sent us, it always got lost somehow. We never received anything from them. It went around the family how we almost received red chamois dresses from Uncle Lajos, which were stolen from the man with whom he sent them. It wasn't true, of course [that the presents got stolen]. Or if it was true, such a thing could only happen to our family. They came home on visits several times before World War II. They came to visit us after the war, too, and I showed them around then.

Dad is from Recsk. But he was born somewhere else, maybe in Erdokovesd. They moved to Recsk when he was a little boy. He came to Eger at the age of ten and became a tailor's apprentice. He was sent to Eger because there was no tailor's workshop in Recsk. And he was sent at a very young age so that he could earn money as soon as possible. He was an apprentice at some relative's workshop. He was an extremely skinny little boy, thin and weak, and he had to lift those terribly heavy irons, because the irons used for menswear were extremely heavy then. The iron was basically a block of iron; it was put in the fire and heated up.

This aunt, or whatever relative she was, was worse than a stranger could have been. She kept pestering him, she always sent him here and there, to do the shopping and so on. Apprentices were very badly treated in those days. These apprentices who were bound to their masters by force still learnt sewing somehow or other. The worst thing was that they had to run around a lot, but only got very little food. They weren't regarded as relatives whom one would feed or treat better, it wasn't customary in those days. From what I gathered from Dad's stories, it was a tough life.

Dad was an apprentice for three or four years, I think. And when one had served his apprenticeship, he either stayed with those he had been an apprentice to or went to work for someone else. Dad worked for this relative until he got married. He lived at this relative's place. It was a big favor that he could stay there.

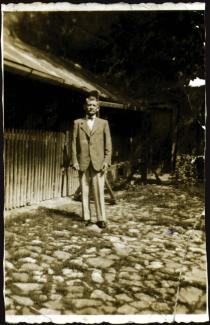

Dad was a master tailor, and a gentlemen's tailor at that. There was another tailor opposite us, he was a peasant tailor, as it was called back then. A gentlemen's tailor made proper suits. My dad was a very accurate, meticulous master tailor, he turned out beautiful work. Not so long ago, my grandson, Andris, found an article from Eger about Dad in which they said what a remarkable tailor he was. [In fact it was not an article but an entry in a book entitled 1930 Almanac of Hungarian Craftsmen, in which his name, age, profession and place of apprenticeship is mentioned.] Dad had his workshop in the same house we lived in. We could only go down to the workshop when Dad didn't see us because he didn't like it when children were hanging around there. Dad was a very strict person, but he was a good man; he loved his family and he was very fond of children.

He had three employees, two apprentices and an assistant. The assistant had already finished his apprenticeship. The assistants weren't Jewish, and the apprentices weren't either. The apprentices were peasant boys from the countryside; they stayed in his workshop for two or three years - it was regulated how long they stayed. Dad taught them to sew and then he tested them. The apprentices slept in the kitchen. They brought in their beds in the evening, put them on the floor and that was it. The apprentice got the fire going in the workshop early in the morning, made a fire in the stove for these heavy irons and put them into the fire to heat them up. Dad went down to the workshop at 7am. The workshop was the size of about half of this room [about 6 square meters], and his only wish was that someone would inherit it from him.

Dad earned a good living. It wasn't only Jewish clients who came to his workshop, but all those who could afford it. He was an expensive tailor. There was a jeweler, who didn't have money - he had quite a lot of children and he was also Jewish - and he said: 'I can't pay you, but I will give a piece of jewelry to each one of your daughters'. So each of us got a ring, and I almost didn't get one because I was the fourth child. Considering that Dad was poor, he always paid especial attention not to cheat anybody. In those days merchants from Pest used to consign fabrics to tailors from the countryside. Dad sold the fabrics but he never cheated the merchant or his clients, regardless of whether he made a profit or not. If he was given anything in consignment, he accounted for every cent. So he was very honest, he never wanted to make a fortune on someone else's account. Dad didn't have many Jewish friends because he made friends mostly with tailors. Some of them had some land or a small vineyard, and they used to get together and have a little booze-up. Dad used to join them.

We helped quite a few family members as much as we could afford to. There was one relative on my mother's side, Uncle Naci and his family, whom we helped. He was my uncle, Mom's full brother. They were very poor. Uncle Lipu's family also helped them but it wasn't very pleasant because they were such disagreeable people. We baked every Friday - Mom was great at baking, she could make wonderful cakes - and the first thing we did was to take some over to Uncle Naci's family. I used to take the pastry on a small plate on Saturday morning and say, 'Aunt Etelka, I brought some pastry'.

We had some relatives on my mother's side in Eger. Most Jews lived in one quarter, in the center of town, in Dobo Street, Dobo Square and Magyar Street. It had developed like this by chance, but when I think of it, I can see the stores in my mind's eye. Grocery, haberdashery and whatnot. Almost all my relatives were storekeepers. The Jews were mainly involved in commerce; they were greengrocers, they had various stores. There were non- Jews in this quarter as well, but not too many. And there were some Jews scattered in other parts of the town because Jews continued to come to live in Eger from the villages around. But Jews and non-Jews didn't mix, Jews didn't move to the Christian quarters. They didn't want to and, I guess, couldn't have moved there even if they had wanted to.

When they got married, Dad and Mom lived in a rented flat on Dobo Street. There was Rosenberg, the textile merchant, and my father rented the house from him. The apartment wasn't big. We had two rooms, one for the parents and one for the children. There was a small stove in the room, and wooden floors - I remember that we had to scrub them.

Electricity had already been installed in Eger by that time. But the water pipes were only installed in the second half of the 1930s. There were one or two artesian wells, and we used to go there with a bucket to get drinking water. Everybody had rainwater in a barrel in his yard. We had rainwater in the summer, too, we collected it from the gutter. I loved it; we used to go out early in the morning, and we would splash about in the barrel and take some in to wash ourselves. We had to wash up every day. We went out to the barrel in the winter as well. We would put on a shawl, fill up the basin and take it in. Most people think that we didn't have water in those days. But we always had water, only you couldn't drink it because it wasn't good.

When we were little, we had a trough and we bathed in the trough one after the other. I remember the times when I had to bathe after my sister Bozsi: it took her a very long time to get out of it and I was angry with her. But we couldn't have done it otherwise because there wasn't enough water [for everyone to get washed separately]. Once a week before Sabbath we heated water for bathing in a laundry pot. We had a regular stove in the kitchen, which we heated with wood.

Mom was a housewife, as all women at that time who had many children. This [four children] was already considered many children. I don't know how my parents met; they never talked about it. Mom was 17 or so when she got married and she gave birth to Piri soon after. I was born in 1915, Bozsi in 1910, Rozsi in 1908, and Piri was born in 1906. She was a very beautiful girl. Piri always ran away from home. Once she ran away to the neighbors and they were standing over her at a loss, wondering who she could be. She was a nice blond little girl and she could already talk, only she couldn't tell what her name was and who her father was. And finally they found out who she was because she kept saying, 'He is always ironing, he is always ironing'. And so they realized that if he was always ironing, she could only be the tailor's daughter.

I was the youngest child and the fourth girl. My father almost threw me out! He said that if I was also going to turn out a girl, I would be thrown into the Eger stream. He didn't mean to throw me out, of course, he just kept threatening my mother with it because he wanted to have a male heir who could inherit his workshop. Looking back at my childhood, it was absolutely untroubled. It wasn't an issue whether we were Jews or not. We were on very friendly terms with our neighbors. We didn't get together but we got on well. In school [non-Jewish] children were told that on Saturday they had to write the stuff in our student's record and everything was going well. Nobody touched us, all the more so because my dad was a very honest and decent craftsman.

We had a servant. In the countryside everybody had Hungarian village girls as servants, and so did we. This was in fashion at that time, it was a rule, one had to comply with it. Servants came from the countryside. There were people who recommended them, that is, middlemen who did this for a living, but people usually got their servants through acquaintances rather than through them. The servants didn't change often, we had several who stayed with us for years. But I remember the apprentices more because they helped a lot. When Mom was very much behind with something, they helped to do the shopping or carry heavy loads and things like that.

The servant helped with all that Mom did. Mom did the shopping but the servant went with her and helped her carry the stuff home. Mom did the cooking, the servant didn't cook but helped in the kitchen. She peeled the vegetables and Mom let her do the washing up as well. The cleaning was also done by the servant - every day, as was customary in those days. There was no extra space in the apartment, of course, but we had a kind of shed and the girl lived there.

A washerwoman came to do the big laundry. I can't tell how often we did big laundry but it was also a ritual for which we had to prepare. It went on for several days and it was a terribly awful lot of work. The big laundry was done in the courtyard; and in the winter it was done in the kitchen. We had a wash-house but it couldn't be done there because we had apprentices sleeping there, too.

There were two synagogues in Eger, a Neolog 4 and an Orthodox synagogue, and both were close to us. We went to the Orthodox synagogue [on high holidays] but on Fridays we went to the Neolog one. Dad usually didn't go to the synagogue on Friday and Saturday because he wasn't so religious. Mom used to go every Saturday. She put on her nicest dress and proceeded to the synagogue. Sometimes she took me along, other times she didn't. We used to chatter and chortle and laugh a lot. We could make a pass at boys from above [from the women's gallery] because there was a grid, some kind of a railing and we leant over it and ogled at them. The adults let us do everything, there was no supervision. You went in, you were there, you went with your mother and that was it. But they [the adults] really prayed.

The other synagogue was Orthodox, there you couldn't look down and do other 'nonsense'. There you couldn't really see through the grid and they had different rules. We went to the Orthodox synagogue on high holidays when several people fainted. We always knew in advance who would faint because there were some women there who had eaten a lot the previous evening [before the fast started] and the following day we were waiting for them to collapse and they were then taken outside. But we didn't take all this seriously, it was all just very interesting and funny to us. My parents had their own seats; they had to pay for them.

As a matter of fact we were both Orthodox and Neolog. Because we were Neolog through Dad and Orthodox through Mom. My mother's family, the Pollaks, were all Orthodox. There were sometimes disagreements between Dad and Mom because of this because Dad worked on Saturday and Mom didn't really like that. I wouldn't have liked it either if this had been my conviction. But I was only a child then, I couldn't grasp it. I just always heard their dispute: 'You work, you don't observe Sabbath'. But Dad was also Jewish in his spirit. Mom strictly observed all Jewish traditions. First of all, she went to the mikveh as required - one had to go once a month. I can't remember any more why we had to go there once a month.

There were some steam baths in Eger and one was opened for the Jews [on Friday]. It wasn't a Jewish steam bath [a traditional ritual bath]. It was an ordinary steam bath and there were occasions, usually on Fridays, when Jews could immerse themselves. I used to go the steam bath with Mom. Mom went there to immerse herself. I liked going with her because this way I bathed more often than my sisters. They used to go with Mom when they were little, too. But I don't remember that because I was the youngest.

We had a kosher household. We bought kosher meat and we took animals to the butcher for slaughtering, but I don't know what he did with them. [Editor's note: The interviewee is talking about the shochet who kills poultry.] And we only ate goose. As I mentioned before, Aunt Szeren, who lived in Kal, used to buy geese there and brought them to Eger every weekend, and she sold them with Mom's help. And Mom always kept one for us and we always had smoked goose, goose leg and other such delicacies at home. The dairy and meaty dishes were kept separately. When I was older I used to eat ham, too, although I wasn't allowed to take it into the house. Mom knew about it and she told me off. So, it wasn't taken that seriously toward the end.

We usually had goose or chicken fricassee. We recited Kiddush Friday night; we had barkhes [challah] for that. The baker made it and we bought it in the bakery. We had cholent on Saturday; there was goose neck and all kinds of delicacies in it. It was put in a pot, and the handle of the pot was fastened because the pots were thrown about in the bakery. Many people took their cholent there. We had to write our name on a piece of paper and fix it to the pot, but sometimes the name got burnt and the pots were muddled up and we had to go and find out who had taken ours. But there weren't so many Jews there that we would have had to be concerned about where our cholent had gone to - we never ate someone else's cholent, we always knew who the individual pots belonged to. I remember that we went to get the cholent on Saturday, and we could hardly wait for it. We brought it home with the servant. On Saturday it was the servant who lit the stove for us; they were there for doing that.

We always did a proper house-cleaning before the holidays; it was unthinkable not to, it was a must. We also did cleaning on Friday. We did the cleaning before Pesach and also got rid of the chametz. It was Mom who knew best how to do it. She did it as she had been taught by her mother. And her mother knew well how to do it because she was a Pollak. But I'm sure that she had inherited these traditions from her mother in turn. It was always Mom who did these things. I can still see her before my eyes with her little apron as she was getting rid of the chametz. I can't remember very well how she did it. I remember, though that they wrapped something into a cloth. They gathered the breadcrumbs..., I don't really know this part. I've never done it myself. And we did the housecleaning - that was a great event for us. The Pesach dishes were in the attic and we had to climb up there on a ladder and we had fun as we were handing down the checkered mugs; they were so beautiful, these dishes, I can still see them in my mind's eye - but we only used them during Passover.

We all spoke Hungarian as our native tongue in the family. My mother's line knew German and Hebrew. The Pollak grandparents spoke in 'Polishi' [i.e. Yiddish]. I sometimes heard them talk in 'Polishi' but I didn't understand it, I didn't speak that language. I heard it from them but I didn't pick it up. And we didn't study it either. We learned German in school and everywhere. It was very good for us pupils.

There was a theater in Eger. I can't say that we went there often because there weren't performances so often. There was a cinema, too. And there was a place in the Korona Hotel - I don't really know what to call it - where we could entertain ourselves; dance classes took place there and other things. I didn't go there very often because I didn't like it, I don't know why. My parents always paid attention to having an overseer for the girls. I was the main overseer - and how I hated it! I kept telling Bozsi, 'Look, I won't go with you. Leave me alone'. But I had to go because Mom told me in a peremptory manner, 'You will go with Bozsi and take good care of her'. But it was such a nasty job, so horrible because they didn't like having us go after them all the time.

The Jews had a special place which was maintained by the Jewish community and where even an artist, a reader of poetry, used to come to perform. He was a famous Jew, but I can't remember his name now. And all the Jewish children went hiking together, without parents - the youth was progressive.

There was a swimming pool in Eger. It was unthinkable that someone couldn't swim; we all knew how to swim. I learnt to swim at the age of 3; I was taught by a swimming instructor. Mom was standing next to me and was having kittens that I would be thrown off from the spring-board and would drown. And the instructor took me up the spring-board, threw me off and that's how I learnt to swim. We loved the swimming pool, we used to go there the whole summer. We went there in the morning and waited in the courtyard of the swimming pool until it was opened. When it was opened, we ran in like a bunch of puppies and we got into the water and out and in again - it went on like this the whole day. We didn't have any food because we didn't take lunch with us, but we had fruit because Mom always bought a whole basket of fruit and distributed it among the children in the morning. They didn't have to worry about us, we had a great time and Mom was free, too. We, children, simply loved the swimming pool.

My parents also went to the swimming pool occasionally, my mother swam very well. Dad didn't go swimming, he worked. But Mom used to go regularly. We used to go to the swimming pool with Jewish girls. At that time men and women bathed separately. The Catholic Church didn't allow a common swimming pool - we children knew about this, too, it was no secret. It was a 'sin' for men and women to swim or bathe together. This is especially interesting because the canons - these were priests with purple belts - refrained from going to such public places [in Eger]. At the same time many people saw them in Pest going to swimming pools and the lido. Well, this was really not reconcilable [with their position] and even we children reprimanded them for this, although it was none of our business. When the [common] open- air swimming pool was finally allowed, Eger started to prosper because it gave a boost to the town. Eger became a busy town; cheap trains started to come from Pest. People could take cheap trains to come to the open-air swimming pool in Eger.

Eger was under total clerical rule - it was an archbishopric. The Catholic priests intervened in everything. Whenever the issue was raised how good it would be if the town developed, they always put obstacles in the way. This way the town didn't really make progress. The canons lived all along Kaptalan Street. They all had beautiful houses, riches and land; they wanted to rule everything. And they succeeded. When my poor mother killed geese, they always took the liver to the canons. My father worked for several canons. And they bought the liver from us. They reigned there, so to speak. They had everything you can possibly think of and I'll never forget that there were peacocks in these houses. Their pantries were as big as these two rooms together and there were huge pots full of lard in them. When the apprentices who worked for us went in there, they always came home awestruck by what they had seen there, by how rich these people were. We weren't at home in this wealth and abundance, although we weren't so poor as to starve, but we lived in a Jewish world nonetheless.

I went to the Jewish elementary school. I was accepted to elementary school before I reached school age [age 6]. Mom took me to the school to enroll me. I still remember that day; it was raining. When old Biedermann saw who it was, he asked her: 'Why did you bring this child, she isn't six yet?' I hadn't turned six yet because I was born in November and school started in September. And my mother said to him, 'Please accept her, they are all clever!' And old Biedermann was listening to her lamentation until he accepted me. But he said that he didn't mind because he knew that the Friedmann sisters were all clever. All four of us were very good students. In class I always had my hands up - as soon as they asked something, I put my hands up to answer it. My friends told me later, 'You always knew everything, you were horrible!' They couldn't bear this; but I was always ready to give a prompt. I only have one friend who had already been my friend in elementary school; I still call her from time to time.

Then I went to middle school 5. It was a state school and we all studied there free of charge. I even learnt to play the piano for five years, so we were really trying [to get a bourgeois education]. Piri also learnt to play the piano a little. I would have very much liked to continue studying because I had an ear for music and I had a private teacher. When I was in middle school, they [the teachers] made it possible for me to observe Jewish religious traditions. On Saturday they asked the non-Jewish children to write down in our student's record what classes there would be next week and whatever else had to be written down. I had a friend, or more precisely a classmate, called Piroska Toth, who used to note down for me what homework we had for the following week. We weren't allowed to write on Saturday. It wasn't so much Dad or Mom who expected me not to write on Saturday. This came more from the Jewish community and schools weren't anti- Semitic in this respect. Some made remarks about this but they made everything possible, and I went to middle school each Saturday from the 1st grade to the 4th grade and didn't write, and it wasn't a problem.

All my sisters finished the four classes of middle school. My oldest sister Piri also finished two years of commercial school. This was a commercial high school, where nuns taught. And it was very expensive. If someone wanted to work in an office then she, like my sister, finished two years of commercial school and then she could become an employee [in an office]. There was a car dealer in Eger - there was only one at that time, there were hardly any cars; we went everywhere on foot, it was a small town, we could walk from one end to the other in two minutes - and Piri worked for this car dealer. My parents had more money for the education of my older sisters; by the time it was my turn, the money was gone. Sewing was almost the only trade that one could always do for a living for sure. So, they decided that the girls should learn sewing.

Girls didn't really have the possibility to learn any other trade at that time, especially if they were Jewish. Bozsi worked for a family, acquaintances of ours - people often learned a trade through acquaintances. It was very good that we didn't have to go to an unknown person to learn the trade; everybody new Dad and everybody liked him. So, these were really the good old times. All my sisters knew how to sew except for Piri, who worked in an office. She couldn't even sew a button on, she struggled with everything that had to do with sewing. Bozsi sewed for sale, and Rozsi was at home after finishing middle school and helped Mom. She made beautiful children's clothes. I have no idea where she learnt this, she probably just picked it up somewhere. She never learnt it professionally.

Bozsi married someone from Pest. She had a great love in Eger, a boy called Pista Deutsch, but his mom didn't allow him to court Bozsi because she was a rather poor girl. They used to meet but you couldn't really oppose your parents at that time. We had to follow the traditions in everything. Pal Spiegel was recommended -matchmaking was common in those days. Spiegel had a pickle-producing workshop. It was a family business. Bozsi didn't work. In those days not everybody worked. Her husband provided for her.

They got married in 1937, but they lived together for a relatively short time. Their daughter, Julika, was born in 1939. The troubles started in 1944 and by that time Pal was already dead. He committed suicide because he had asthma and couldn't sleep at night, so he jumped out of the window. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery, but I don't know the details how this could have been arranged. I don't know, someone must have managed to get the permission, probably the relatives. The whole family was shaken. Nothing like this had ever happened in our life. He was a very intelligent nice man, only he wasn't healthy. But we didn't know that when Mom married Bozsi to him. [After his death] Bozsi returned to Eger and lived with Mom and Dad and sew clothes for others. She had to make a living from something.

Piri's husband was Gyula Krausz, he was a merchant. They got married in 1926. We had a cousin, Bela Korosi. He was somewhat of an eccentric but he was a lawyer by profession. He courted Piri. And Piri was about to marry Bela, the wedding was to take place within a week. But nothing came of it because in the meantime Gyula Krausz also proposed to her. Mom went to Reb Shayele, who was a rabbi, who told her not to marry her off to America and that there was this decent fellow here and she should marry her to him. We children were eavesdropping, of course, and heard Mom tell what the rabbi had said. The end of the story was that Piri didn't go to America. She had everything ready, all the papers, but she didn't go to South America. She was just as 'enterprising' as the other members of the family. That's how we became mies instead of becoming Miss. This saying - why we never became Miss - went around in the family. [Editor's note: The interviewee refers to the fact that the family could have gone and lived in America, and thus Piri would have become Miss, or an American citizen. But since their father was not enterprising enough to emigrate, they remained in Hungary and weren't very happy, but "mies", German for wretched, pronounced "mees"].

Piri lived in the 7th district in Pest, where I also lived later when it became a yellow-star house 6. Her husband died somewhere in forced labor in 1945. Piri took over her husband's job after the war. She picked up bread in the big bread-producing factory and took it to various shops. This was an independent occupation at the time.

When I finished school, I also wanted to continue studying, as Piri had done, but I couldn't because the nuns didn't offer a commercial course that year. My parents tried to place me in a lawyer's office but business was running low - the lawyer was a relative of ours and he did my father a favor by employing me, but I didn't earn any money. After this job, I decided to learn how to sew. My parents apprenticed me to a man, also a tailor, who was an acquaintance of my father, but I didn't like it there at all. He was a Jewish tailor from abroad, not from Hungary. He was a women's tailor. I was there for only a very short time because I kicked up no end of a racket at home about not liking to be there. But I still learned how to sew, since we all knew this trade kind of instinctively because Dad was a tailor.

The Greiners, my husband's family, lived in the same street as us. I went to work for Dora Greiner. Three or four of us worked in her workshop. Dora was our boss. She was very strict; she used to upbraid me all the time before she became my sister-in-law. After her brother married me, I used to tell her, 'You were such a nasty boss, it was horrible'. I worked there as an apprentice for a couple of years and I didn't get a salary; we were happy that they took me on in the first place. After I finished my apprenticeship, I got a salary for my work. But we didn't have set working hours. We were told at what time we had to start in the morning. I can't remember what it was any more. I guess it must have been 7 or 8 in the morning. And in the evening we had to stay until we finished the fancy work on a piece or whatever we were doing. As long as the Greiner girls lived in Eger, I worked in their workshop.

I was working in the sewing workshop of my husband's older sister and I 'kept repairing the iron' until my husband fell in love with me and I with him and we married. I liked him very much because he was a smart boy. He wasn't the most handsome boy in town, but he was very smart and I always liked to learn things. He was great, my husband, very witty and smart and intelligent. And you could learn everything from him that you ever needed in life. My husband set my attitude to many things; because he was a communist from the beginning, already before the war. My husband was a very decent man and I adopted many of his views because he was an authoritative person to me. Later I also became a real atheist because my husband was a communist.

The whole Greiner family was like close relatives to me because we lived in one street. They were very decent people. In Eger they were called the 'decent small people' because they had never had much money but they weren't poor either and the children never went about dirty.

My husband came from a religious family. His father was a Torah teacher at the Jewish community of Eger. There was a school and the more religious Orthodox children used to go there every morning. The old Greiner was very quick on the uptake. He was very original and smart. He had a beard and payes. (My husband and his brother also had payes.) But he wore a suit like anybody else. These Orthodox didn't ware a caftan any more. They were kosher and I remember when my poor father-in-law put the fish in a vat every Friday and scaled it. He had to do it because he was employed by the Jewish community.

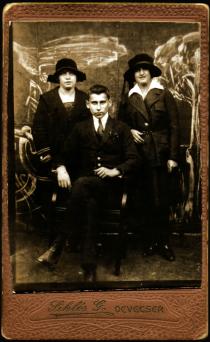

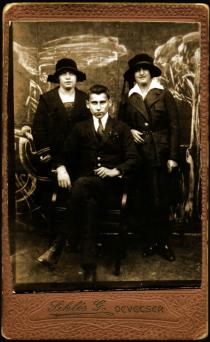

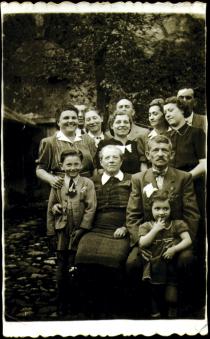

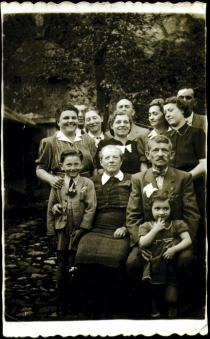

The Greiners had six children: four girls and two boys, namely Szeren, Elza, Dora, Mandi, Arnold and my husband Pista. In those days, if someone had six children, people didn't think they had many children. In some Jewish families there were ten to eleven children.

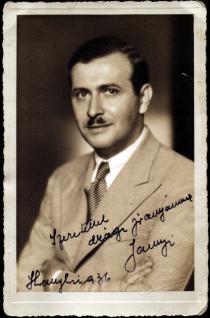

My husband was born Izidor Greiner. Then he magyarized his name to Istvan Koltai in 1946. [The pet name of Istvan is Pista.] They had lived in Kolta and when he was asked after the war what he wanted as a surname, he said Koltai. [Editor's note: In Hungarian the letter 'i' is added to a place name to refer to people from that place, so koltai is a person from Kolta.] He was often asked if this or that Koltai was a relative of his and he always answered, 'Yes, if he had been called Greiner before'.

Pista was born in 1907. He was born in Kolta. But they moved when he was one or two years old. My husband and his brother didn't go to a regular public school because there was no Jewish school. They went to a yeshivah. They went to a yeshivah somewhere in Upper Hungary. Later my husband told many stories [about the yeshivah], he could tell them in a very funny way, but I don't remember any of them. I can't tell you for how many years they attended the yeshivah.

So, Pista was raised in a very religious family but the whole company kind of went wrong, the children, I mean, because none of them were religious. All of them were very smart and intelligent. The Greiner siblings didn't care a pin about what their parents told them; they didn't listen to them, they went their own way. They were right. But it was only later, after their parents had already died, that they got involved in politics. They observed all precepts of Judaism that their parents forced upon them but they didn't believe in these things. My poor father-in-law was a very intelligent man, so he accepted these things as they were; he accepted that one had to let young people go their own way and do as they think is best for them.

Their poor parents died very young, I think around 1930. The girls were left alone and they were thinking about what to do and decided to move to Pest. And they did. Dora and her sister Mandi joined forces and brought the sewing workshop to Pest. Their workshop was on Terez Boulevard and I used to go there as if I was going home. I went to see them more often than my own sister. They accepted me in the family as if I were a sister to them. We were very close, they were very humorous and quick-witted, and I loved them. We were almost like sisters, we grew up together. I knew that I could always rely on them.

Mandi was the youngest. Her husband, Gyuri Gardos, participated in the [communist] movement here in Pest and I had many acquaintances through him here. Mandi has already died and her husband as well. Her daughter owns a store.

Szeren married a man from Szarvas and settled there with him. She was called Mrs. Joachim Schwartz. She was the eldest of the Greiner sisters. She had two daughters, who were deported, and a son. They survived. They had been deported to Austria and children had more of a chance to survive there. They emigrated to Israel and Canada right after the war.

Elza got married in Pest and she didn't have any descendants. Arnold was the youngest boy. He was a painter. Poor Arnold died of spotted fever in forced labor somewhere on the Western frontier of Hungary. He has a memorial plaque in the Jewish cemetery in Rakoskeresztur along with the forced laborers killed in Balf. He had been in Balf, too, and he met my brother-in-law there.

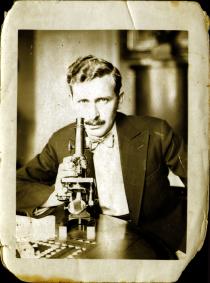

My husband worked as a clerk in the lumber-yard of David Schwartz. He was a very talented, smart boy, so he graduated from high school. He was a private student and who do you think helped him prepare for the graduation examination? My cousin, one of the Korosi boys - but it was pure coincidence because we weren't related to the Greiner family at that time yet.

My husband was a member of the Social Democratic Party. He was even imprisoned for four months in the 1930s. He was arrested in Eger. The gendarmes arrested him in Kostya - that's a quarter of Eger where mostly peasants lived - for distributing illegal literature: pamphlets and books but I don't know exactly which ones. He was in prison for four months; he spent two months in Eger and two in Pest. I recognized him as my fiancée and I was judged by the same criteria, only he was in prison and I wasn't. He learnt German then. He very much wanted to be fluent in German and he studied it in prison until he became fluent.

Pista courted me for a very long time because he didn't have a job. He had lost his job because of his arrest. He had to leave Eger and its environs because the police kept looking for him at my father's place. And Dad kept telling them that he had no idea where he was because he didn't keep in touch with him. Finally Pista got a job in Fejer County; there was a lumber- yard in the village of Cece. There were many vacancies; they were advertised in the papers. However, we could only choose a job at a lumber- yard because that was Pista's profession. After graduating from high school he had learnt this trade. The lumber-yard in Cece belonged to David Schwartz. My husband worked for two people by the name of David Schwartz. One was from Sarbogard and the other from Eger.

We got married in Budapest in 1937. He had already got this job in Cece, otherwise he couldn't have married me. The rabbi married us in Dora's flat. It was quite natural at the time. Most communists were Jewish. And since our parents accepted that we were modern, we accepted that they weren't. So we did all we could for their sake. My sister Bozsi's wedding was on the same day but in Eger. My parents were present at both. I have no idea how they did it. Dad did his utmost; it wasn't so easy to marry off two girls, but he managed somehow. He didn't give me a dowry but my husband wouldn't have accepted it anyway. Pista boarded at my parents' for years.

We lived in Cece from 1937 to 1942. When I got married and moved there, I thought that I would move to a normal place. But when I got off the train in the evening and started looking for the village I found nothing. Because it really was just a village compared to Eger. So, I got off the train and said to myself: 'It's ok, I will find it in the morning'. And I woke up the next morning and there was nothing there, just the wilderness. I just couldn't stand living in a village. Eger wasn't a big place but it was still a town. However, I had to get used to village life because I knew that my husband wouldn't find a job anywhere else.

Our house had two rooms but I couldn't furnish both, I only had enough furniture for one. We had some animals, geese, ducks and so on and we also had a garden. I was always very active, and I learned about gardens and gardening as well.

There was a farmer at the lumber-yard, who looked after the lumber-yard with his family. He was in charge of the goods and he gave out the merchandise to the customers. Pista worked in the office. Those yard people helped us in all they could. They were called yard people because they ranged the tiles and everything else. We always had many dogs and we had to have many because the money [the daily returns] was always there until we mailed it in the evening.

Cece was a shitty little village. The Jews there weren't religious. We didn't observe the Jewish holidays either. In the village we were friends mostly with the Jews. All in all there were four or five Jewish families in the village, merchants and an ironmonger. The Bar family owned a haberdashery. I was on good terms with the wife. We used to get together to play cards like villagers did in those days. And Pista and I studied French there - without a teacher; we just had a dictionary. We had a lot of time at our hands and we didn't know what to do in the evenings. We just studied on our own. I was quite good at writing in French. And I learnt French spelling to some extent. I liked studying it, but I couldn't really learn it properly because I didn't have a goal in mind with French.

I didn't go home to Eger very often; it was too far. When I had enough money, I went home. I visited my parents every year. Mom and Dad came to see us in Cece, too. And they liked coming because I did my best to make sure they enjoyed their stay.

Pista was drafted to forced labor for the first time in 1942 - he was taken to Tokaj [wine-growing hilly region in the north-east of Hungary], and to other places as well, I can't remember where any more. As soon as he was back, he was always drafted again; always for a few months at a time. So I had to learn everything [at the lumber-yard] because I took over and ran it when he was drafted to different places. And everything went smoothly. Nonetheless we had to be very careful because there was a lot of open anti- Semitism already at that time. But I don't remember any particular incidents because the whole thing became so natural toward the end.

Pista didn't join any party activities in Cece; he couldn't have done so anyways because he was there undercover. Toward the end of our stay there the notary discovered us. They didn't know who we were until then. Actually, we were hiding there in Cece. It seems, however, that the police had a long arm. And they found out that he was a communist. Pista was called in and the notary told him that we had to leave the village within a week, and that was it. He didn't give any explanation whatsoever. The same happened to the other Jews in the village, they also had to leave. Everybody was kicked out of the place they had lived in. Pista had had quite a good salary, so we had bought all that we needed and could get there. And then this scum of a notary kicked us out of the village. We had to sell everything. We had to advertise it and the villagers came and took everything, all our belongings, apart like madmen. It was horrible! When we had to leave the lumber-yard, a Christian took it over, he was a front for the owner [who was also a Jew and Jews tried to secure a front to avoid losing their business when it had to be Aryanized].

Pista was probably in forced labor at that time already, and he was home just [for a short stay] then. So I had to move to Pest alone. We had an acquaintance in Pest, a tailor, and Dad arranged with him that we went to live at his place as lodgers. When Pista arrived in Pest, he sold pastry at first. In those days many pastry shops baked pastry and Pista, like others, used to deliver the pastry packed in boxes to the stores on a bicycle. He got on the bicycle and did the rounds of the stores. My sister Piri's husband delivered bread. And that's how he knew to which stores pastry could be delivered.

We never thought that things would degenerate to this point. It really took us by surprise. We read the anti-Jewish laws in Hungary 7 but we would have never thought that such things would happen. We were so naive. In our previous life, so to speak, we had never experienced that we would be told that we were crap, the lowest of the lowest, just because we were born Jewish.

There were warning signs but we were so naive that we simply weren't prepared for this and, to tell you the truth, the leadership of the Jewish community should have been more decent and honest with its members and could have told us what they thought about this, if they thought anything at all. But they took the rich Jews out of the country. [Editor's note: Panni Koltai is referring to those rich Jewish families, which bribed the SS and the Hungarian authorities to let them out of the country. The most spectacular affair was that of the Chorin, Kornfeld and Weiss family, which handed over the Weiss Manfred Works, the largest engineering industry plant of Hungary to the SS in exchange for letting them leave the country.] They didn't have to hide, they paid and they went abroad. But we stayed because we were nobodies.

One could never really be prepared for what was to come. The Germans occupied Hungary on 19th March 1944 8. I went home to Eger twice - the first time a week before the Germans arrived and the second time on 18th March. At first I just went on my usual visit and then I just decided to go again. Somehow I felt that I had to go once more. At that time I was already living in Pest and our Julika - my parents' only grandchild - was already living with her mother Bozsi in Eger, and we agreed that I would go to see them again the following week. Well, did I go?! By that time the Germans had already occupied Hungary and we couldn't move at all. Whoever set a foot outside their building was caught by the Germans and off they went.

The forced laborers were taken away, some came home from time to time, others didn't. My husband was in forced labor, he was drafted, then sent home, then drafted again. This happened several times. When they felt like it, they drafted him. Those who were clever and smart did something to avoid it. But one couldn't really evade it. It was too well organized.

We received postcards from the Jewish community, which said that my parents were alive and fine. Everybody was 'fine', only they were no more alive. They were exterminated on 7th June 1944. They had been taken to Auschwitz - my mother, my father, my sister Bozsi, who had a little daughter, Julika, and Rozsi. Rozsi was married and her husband was in forced labor somewhere, and he also passed away. All the Jews in Eger were collected. The ghetto was simple. They said that it would be where the synagogue was, next to it there was a what-you-call-it, and they were collected there. I don't even know how it exactly happened in Eger. When Rozsi came back, we didn't question her because we felt sorry for her. Bozsi and her daughter were gassed immediately, just like my parents. Julika was six years old. She was a beautiful little girl, smart and intelligent, and she was to start school that year. They would have never thought in their worst dream to what place they were being taken. Who would have thought that such an evil thing could happen in civilized Europe.

It's pure luck that we have survived; because we had been taken to so many places. We lived in a rented apartment, then we moved to my sister because Jews had to move to yellow-star houses. My sister Piri lived in the 7th district and her building became a yellow-star house. And it was simpler to move in with my sister than with a complete stranger. There was another Jewish woman in the apartment who was sent to live there by the Jewish community or someone, I'm not quite sure. My sister worked; she delivered bread to stores. I did some sewing for people in the building. The Arrow Cross 9 men often came in the evening or in the morning and drove us out of the apartment. They told us that we had to go to the Turf. And then we sat there on the ground the whole day and ate. And then they changed their mind because there wasn't any place where we could sleep and it was already 11 at night or so and they told us to get the hell out of there and go home.

Once they came and drove us out of the apartment to the Turf. And I wore the ring, which I had received from that jeweler through my poor Dad. I thought that I'd better hide it. And I heard from several people that one could open the lower part of the toothpaste tube and hide the jewelry inside the tube. Who would think to look for jewelry in the toothpaste? And in the morning I was pondering on what to do with this ring of mine because I had nothing else by then; I had been deprived of all my things. And I had a sudden thought and threw it down into the courtyard - it was a typical apartment house with a square yard that you find so many of in Pest - just to make sure that at least they [the Arrow Cross] wouldn't lay their hands on it.

We were sent home in the evening. We gathered our stuff, our packs and everything, and we started off home on foot. I couldn't believe that they really let us go home even when we were already on our doorstep, I kept saying, 'It can't be, they couldn't have really let us go home!' We were already lying in bed - we fell into bed immediately, we were so tired - and I said to Piri, 'What do you think could have happened to that ring?' It just occurred to me then that the ring could maybe save us. She said, 'Come on, let's go down and check'. We put our bathrobes on and a woman asked us, 'Where are you going?' 'Don't worry, we'll be back in a minute.' We went down to the yard in the dark and what do you think we found there: the toothpaste lying on the ground. No one had swept the yard that day: it would have been stupid of the janitor to sweep because there was no one to do it for, there were no tenants. And I was saved by that ring. Later I gave it to the person who really saved me.

I went to the KISOK sports ground 10 as well - one has to try everything, right?! The Arrow Cross men appeared in the morning and they shouted up to us and rang the bell and everything, and we packed all we had. I will never forget this: I used eau de cologne and it had a rather strong scent, and I put the bacon and some other things in the briefcase and put the eau de cologne in as well - I had just been my birthday and I got it from Piri - and it spilled over the bacon and the bread and it was impossible to eat them.

Piri had her leg in plaster because she had had an accident at work and I had to carry her and pull her and take care of her, and I told her that we were in no hurry. As a principle I never hurried no matter where they were taking us. And I never hurried anywhere, it was best to fall behind. God only knew where we would end up when we had to set foot outside the apartment. We settled down there at the KISOK sports ground, we had backpacks and everything on us, we were expecting to be taken away. It was pouring with rain, it was in October, after the Arrow Cross takeover, and all at once someone said that Szalasi pardoned the Jews. We were breathless. Allegedly Szalasi himself appeared there [on the KISOK sports ground]. But I don't know if he really was there. How would I know?! I didn't know him personally. I was never introduced to him. And we were singing the Hungarian national anthem, we, Jews. I said to myself, 'What idiots they are!', but I didn't dare say it aloud. I didn't utter a sound. I was happy to be alive. And we were sent home. We had three or four such incidents, when we were taken somewhere and were later sent home. And then, one day, there was no more messing around and we weren't sent back home. Or, to be more precise, we knew that we had to leave the building because no good would come of it. And so we fled from there.

Piri knew a grocer called Szucs and we went there. He was a client of my brother-in-law, Gyula Krausz. The old Szucs was always coughing, spitting and sickly, but he was an incredibly decent man. There was a gallery above his store from where we could see who entered the shop but no one could see us. If Arrow Cross men came into the store to buy something, he started talking loudly so that we knew up on the gallery who came in. And he held them up. He also gave us food and tried to provide for us as best he could. He had a very large clientele with many Jewish clients. He hid a whole family in his home. His daughters were very nice and decent. He had a big family. His son was in his teens but he didn't grass on us either. I was hiding there with Piri for a while; then we separated. That's how the two of us survived in Pest. If Bozsi had remained in Pest, she would have survived, too, but she wanted to go back to my parents in Eger. And off they went to Auschwitz together.

I have a prayer book, which used to be Piri's. When we were in hiding in 1944, she had the prayer book on her. And she went out to get a Schutzpass 11 through a Catholic friend of hers. And she was halfway already when she remembered that she had a Jewish prayer book in her pocket. She ran back, lest someone would find it on her.

Then we went into the ghetto. I can't remember exactly when. We went when we had to go. We were obliged to go because he [Szucs] was risking his whole family. The ghetto was a calmer place for me. I'm not saying that it was a great place but we thought that it was safer to be inside. We couldn't take everything there, but I can't remember any more what exactly I took with me. There were many people in the apartment where we stayed but I can't remember exactly how many. It depended on which apartment one lived in. I can't tell you any more the address where we lived. It was all so chaotic, so messy. I don't even want to talk in detail about it. We lived in two or three places and then it was all over one day.

Liberation was most complicated because we were in constant fright about how they would execute us. We weren't sure if we would live to hear them say farewell to us. We heard the Russians and the Germans fire away at each other and we were having the jitters. We never knew who was shooting and from which direction. Let's not talk about it. I simply can't talk about it, don't even ask me please.

When the ghetto was liberated, everyone ran wherever they could. I went to the Greiner sisters because we had nowhere to sleep. I only spent a few days at theirs. During the war, when they had all scattered, I once went to see their apartment to check what had happened to it. Dora was in Pest; she had been in hiding at someone's place. Dora had a neighbor - they lived on Lenin Boulevard - and this woman worked at Hotel Beke [which was on the same boulevard]. And she told me that there was some work there. I was really hungry, and I went there and did washing-up in the kitchen in exchange for food. And there was no electricity and so many things were missing that I can't even list them all to you, because such a thing only happens once in one's life.

When we were liberated in Pest, I was walking along the Grand Boulevard and trying to nick some shoes because I didn't have shoes. Finally I went into a shoe shop and everybody was looting there. The store was full of boxes - you could find plenty of shoeboxes there, only there weren't any shoes in them! And I dropped my photos and papers and everything in that mess. I got home and I started looking for the papers and I couldn't find them anywhere. They had fallen out of my pocket. I ran back to the store, of course, and I was in luck's way: I found all my papers.

When Pista was liberated, he didn't know yet that I was alive, he had no idea. We didn't know anything about one another, we didn't correspond [during the war]. I only knew that he was alive because forced laborers started coming back from the front and someone hinted at it that Pista was maybe alive. Then he was told in Eger that I was alive - it's a very interesting story how he was liberated. They were coming back from somewhere, I have no idea from where. And he knew the countryside around Eger pretty well because he had traveled around there on business when he worked at the lumber-yard. One day they arrived in Ostoros and he just slipped away. He stepped out of the row and started off alone.

He went on and on until he found a field-guard's hut somewhere near the village where he could hide. And as he was pottering around in the hut, suddenly some Germans who were raiding the area entered the hut. And they started talking in German; Pista was fluent in German by that time but he pretended that he was stupid. And they started questioning him, asking him who he was and what he was doing there. But he didn't say a single word - where would a Gypsy man know any German from?! Because he looked like a Gypsy, as he was very dark-skinned and dark-haired, and he was dressed in ordinary Hungarian clothes - the forced laborers wore their own clothes. So, finally the Germans left and he thought that it wasn't safe to stay there and decided to go to Eger.

The lumber-yard was near the railway station and he had worked there, so he knew some people there, but they told him, 'How dare you come here?! Don't come here, they just executed someone yesterday'. So, he slid away. And he was hiding in Eger [until the liberation]. Then he came up to Pest and he started looking for his sisters, Dora and Mandi. He found them and they knew where I was because I had been in touch with them all the time - at the beginning, when I went into hiding, and also later on when I was in the ghetto. And they told him where I was and we were very happy to see each other again. My husband took me back to Eger.

Pista joined the Communist Party right after the liberation. Pista already had an apartment there [in Eger], which the Party gave him. And we had lunch at the canteen of the Party - we got bread there but they were quarrelling with me because I got an extra slice as I was pregnant with Karcsi. And they were quarrelling with me because of this; those were such bad times back then. Pista worked in the Party and I also worked there. He was the head of some department but I can't remember now what department it was. He went around the countryside on a motorbike. I was the leader of the MNDSZ in Eger. This stands for the Democratic Union of Hungarian Women. We organized many things. We went around the countryside on a dray or on any other kind of transportation that we could lay hands on. We did many things. We opened a nursery in the garden of the Archbishop of Eger for peasant women so that they could go and work in the fields in the summer. And there was a nursery for their children in the garden of the archbishop as well. All work was done by the same few people until all of them managed to find good positions later on.

Rozsi came back and they had notified us already that she was coming back and then she arrived in Eger in July [1945] and I went to meet her. I will never forget how I got hold of a car and put Rozsi in it. My father had given his gold watch to a friend of his - he wasn't Jewish - to give it to us, his children, when we returned. He was expecting somebody from the family to return. And the guy was skulking off. He used to go to the offices of the Communist Party where Pista worked and he kept saying how he felt sorry for his pal, the poor Ferenc, that is, my father. And then one day when he heard that our Rozsi returned he dropped in to the party offices and said that he brought a watch that dad had given him for safeguarding and he safeguarded it and would now like to give it back. We were dumbfounded because he had met my husband God knows how many times by then, only he hadn't given us the watch back because he wasn't sure that somebody would return. But when Rozsi came back, he thought that we would all come back and start to press him for the watch. This is so typical of people, playing such dirty tricks. And this was Dad's best friend!

Rozsi worked for the Joint 12 in Eger. The Joint set up offices in Eger, too, it had offices in many towns back then. And she was the boss. This was lucky for me because my son was small and she helped me. Later she got married and stopped working. Her husband was called Dezso Schwarz. He was a merchant in Eger and had a stall at the market-place. I don't know exactly what he traded with but I think they made a living from this. Rozsi's second husband wasn't a good man, at least he wasn't good to my sister.

[After the liberation] Piri went home - she had an apartment and she went back there. She then saw that everything had been stolen. The apartment wasn't completely empty but all valuables had been stolen. And then people started to return from forced labor and it turned out that her husband didn't return. My brother-in-law, Arnold, died at the same place as her husband; they were in the same company, but we didn't know it and they didn't know about each other either. They both died in Hungary, in Sopronkohida. Piri continued the same work she had done before the war - she delivered bread on a cart. Later she had many other jobs, she dickered and I don't know what else she did. Both my sisters married a second time and both their second husbands had lost their first wives and children [during the war]. And neither of my sisters had children. I don't want to say anything more about Piri's second husband, Deri, he doesn't deserve it. I didn't like him.

Rozsi remained in Eger. She was ill with cancer for ten years. She died in 1968. Piri died in 1972. Both of them are buried in the Jewish cemetery in Eger, next to each other. We had Piri taken there.

We finally moved to Budapest in 1948. My son Karcsi was already two years old by then; he was born in Eger in 1946. The Party Headquarters allocated us this apartment. It worked like this back then: if someone was transferred from the countryside to Budapest, he was allocated an apartment. I've been living here ever since. I couldn't leave my son to anyone in Eger, there was no nursery school, so I had to take care of him. When we came to Budapest, Karcsi went to the kindergarten of the Party.

My husband was departmental head [of the party membership department] in the Party Headquarters. He traveled around the country; he accompanied these big bosses. He was very much involved in all this. He never talked about his work. And I never asked. I saw it and I agreed with them completely and that was it.

This whole 1956 thing [the Revolution of 1956] 13 was very frightening. We thought that the country would have a quiet time and all of a sudden we had to be afraid once again; we only saw from it what made us frightened. We had done a lot of things out of [communist] convictions because we thought that we were right. We felt that we had done all we could, yet what came out of it wasn't what we had wanted. And we were very much surprised that it turned out the way it did. 1956 was a big disappointment for us.