Silvia Nussbaum

Cluj Napoca

Romania

(Silvia did not know her grandparents which is why her knowledge is very limited). My maternal grandfather Bernat Nothi (1862-1940s), was a notary in a Maramaros village (a village documented as Valea Chioarului, now in Romania). My grandmother was called Fani Braun. She got married at 14, so my mother said. They lived a village life: they had cows, and such. They were really religious. Grandfather taught lots of children, held religious instruction classes. There were even people in Kolozsvar (now Cluj Napoca, Romania) who remembered him (who came from that village). He was famous in that community. Grandmother was also religious, she kept a kosher house. She must have had a wig, at that time she must have had. They observed

religious rules absolutely, at least in the village community. I don't remember anything else. I don't know why but (at the beginning of the 1920s) they suddenly went to Israel (many of the children from the family).

I know about our family but it's possible that others went (from the

village) too. (My mother) stayed here and got married.

There were seven siblings, one died. I know there was a boy: Marton, he was

the eldest (sibling). The boy lived in Israel for a while and then went to

America where he lived for a long time but I don't know what he did. Then

he returned to Israel. I saw him in 1985 in Israel. He was old by then. He

lived in an old people's home, in quite good circumstances and was

completely compos mentis. A few years after, I don't know when exactly, he

died. The others (siblings) were girls: there was a Nusi, a Blanka. They

all went to Israel. Only two stayed here. That means that there are lots of

relations but I didn't know anyone, I never saw them, I only knew about

them, right up until I retired, when it was possible to travel and to go to

Israel. I met their children aged 60. They were born there and only speak

Ivrit. The parents no longer know Hungarian. Anyway most of the parents did

not speak Hungarian but Yiddish, especially the (Maramaros) villagers. Even

the first cousins don't speak Hungarian, not to speak of their children and

grandchildren.

My mother (Zsofia Nothi) was born in 1900, she was the youngest, had a few

years of primary school. She must have been 18-19 when she came to

Kolozsvar. I suppose she came away from the village because of all the

children. She must have had a relation in Kolozsvar as they wouldn't have

let her go off like that (to the unknown). She worked in a factory, but I

don't know what, I know nothing more. After a while she met Izsak Brull.

There was six years age difference. She got married at 23, after they had

gone (her siblings to Israel). She was a housewife then.

I only know (about the paternal grandparents) that they were from

Banffyhunyad (Huedin in Romanian), they lived there but I don't know

exactly where. (The paternal grandparent was called Lorinc Brull). I don't

believe he was religious. There was a photograph of him when he was young

and he had a short beard. But he was a Cohen, as it is (written) on his

grave. I don't know what he did. Nobody told me. They died so soon. All I

know is that they divorced and Zali Friedman (my paternal grandmother)

married again and moved away from Banffyhunyad. (the new husband), Szabo,

was also Jewish.

They (the paternal grandparents) had two children (together): Izsak (my

father) and Helen (who stayed with their father). They had other children

too, who Zali took with her after the divorce to her new husband. Possibly

there were great age differences (between the children). I imagine that the

smaller children: Rozsi, Herman, Farkas, whom she took assumed her new

husband's name of Szabo. But I know of no other (later) relationship

between the two families. Herman went to America. Farkas lived in

Kolozsvar, he was deported.

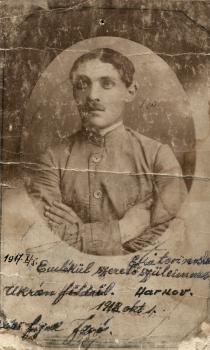

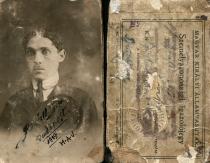

My father Izsak Brull was born in 1894 in Banffyhunyad. He was a thin,

small man. In 1913-14 he graduated from the Applied Arts College (in

Banffyhunyad) and after went to war. He did not speak about the years when

he was called up as a soldier. He didn't speak about escaping from Russian

capture or his travels either. He did not keep up with (his parents, he

just sent a few photographs of himself). That's how the photos, which we

found after his death, remained in the family. From 1914 until the 1920s we

only know (about his life and travels) that which we could make out from

these papers and how he entered ceramics.

He came to Pest young. At first he attended the Industrial and Agricultural

College in Budapest. Then he was a turner and then made ceramics. In Pest

he worked at Zsolnai's and other similar factories (Editor's note: the

ceramics plant started by the Zsolnai Brothers was famous for its beautiful

ceramics and new techniques), but only to learn the skill. He worked in the

mechanic Kalman Vas' workshop too. He was also in Switzerland and leant

about ceramics there. Afterwards he came back to Kolozsvar and until 1935

was at Iris (the Kolozsvar porcelain plant). He got into the Kolozsvar

plant through some sort of mechanics contact, just as it was starting. He

was an intelligent, skilled, very flexible and quick witted man. He saw a

future as a mechanic in the porcelain factory. The factory was set up in

the 1920s, it was Romanian, that is with local capital. A lot of German

engineers were brought in from Germany to run it. (These engineers),

deliberately tried not to teach (the local employees). Because they got

much higher wages than in Germany. Nobody leaves Germany for Kolozsvar - a

completely strange place - for fun, only for better pay. They well knew

that the less they teach (people) the longer their high wages would last.

(My father) then, one could say, pilfered his mastery and learned how to

make porcelain. Slowly he developed into a technical expert at the

Kolozsvar porcelain factory.

In the factory he slowly switched from mechanics to porcelain making, and

worked himself up to become an expert, to the extent that he got noticed

and was taken up by a capitalist called Iliescu. He had a bank and a pawn

shop, today's Transylvanian Bank was his in the past. He had enough money to

say "Come to Torda" (Turda in Romanain) as I am building a porcelain

factory." And he promised high wages. And the agreement went as far as (my

father) saying alright. In 1935 he went to Torda when they were building

the factory. This porcelain factory building was new thing then. In Romania

they primarily wanted to build a factory which ran not on coal, wood or

coke but on gas. There was no gas in Kolozsvar then, it was only piped in

in 1945 after the war. There was gas in Torda (between the two world wars).

And the capitalist was counting on the fact that if he succeeded then he

could (run the factory) much cheaper on gas than on coke. It was a great

risk that Izsak ran doing this because there was no precedent. He could

have failed completely. He had to experiment with how porcelain reacted to

gas, as there were no rules, it had not been done yet. In fact they built

the (Torda) porcelain factory according to his specifications and

experimented with gas stoves and kilns.

Their apartment was right next to the factory, so that he did not need to

go out onto the street but cut a fence from the yard into the factory. They

had a phone put in too. The factory office phone was in his apartment, they

could phone from the factory at 2 in the morning too: "Uncle Brull please

come because the fire in the kiln is too red." He lived in the factory, was

only interested in it. His official title was "conducator technic al

uzinei" (factory tehnical manager). He ran the technical side of the whole

factory. One of his great achievements was the conversion of the kilns to

gas. His other - which also did not exist then in Romania - was electro-

ceramics. The factory converted to electro porcelain (instead of making

porcelain pots). High tension isolators are also made from porcelain and he

had to experiment with these. At the same time (he experimented) with pink

porcelain (its production methods). He was able to surpass, in many ways,

the older and well-known Kolozsvar factory (Iris porcelain).

My father was not religious, he worked on Saturdays too, but went to

synagogue on big holidays because of my mother. My mother ran a kosher

household. She observed the religion, to the extent that she would never

have eaten pork whatever. Even if there was nothing else. But later, we

(the rest of the family) ate it, but she never did. At Yom Kippur, even in

her old age, it was unthinkable that she would not fast. She would have

been sick if she had eaten. My mother lit candles on Fridays. She always

made us fish in aspic and cholent, goose liver and stuffed cabbage. They

did not enter Jewish society, did not befriend Jews. They were mostly among

Germans - colleagues and employees, - as they were in the factory. They

organized evenings, invited colleagues. My mother was very friendly with a

German family who had no children. They knew we were Jews but that did not

bother them. Then there was no difference, they did not make an issue of it

(of the nationality question).

My mother was very skillful and very daring, she was not scared of life.

She worked a lot, did housework for a very long time. Even at 86 she did a

big wash. She never complained. She did not have much time, did not bother

with us much. We had many charwomen, some for a long while. There was a

Hungarian girl - Etel Lorinci - who still lives here in Kolozsvar. In fact

she lived (with us), was brought up with us. Her mother brought her to

Torda when she was 13 to be a servant at ours. And there were others too,

but I can't remember them. My aunt (Helen Brull), my father's younger

sister, looked after us most. She was much younger than my father. We

really loved her. She often went from Kolozsvar to Torda and looked after

us. She was there, we did little washes for her, she played with us and

crocheted clothes for us. She did everything, was very skillful. She wasn't

married then and then she was deported. She came back and then got married.

She went to Israel, in 1982 perhaps.

I was born in Kolozsvar (in 1929, and we moved to Torda in 1935). I can't

remember what we did as children, we must have played. I had a girlfriend

Agi Schlosser, to whom I was always going although she lived at the other

end of town. I always went by bus. We were the same age, her father was

also a ceramicist. She could draw beautifully and was always drawing. She

is in Israel now, but we are not in contact. Or we went to the water's

edge. I was very religious as a child. I had a cousin, Edit, who told me

that if you transgress three times then you won't get to heaven. Then I

thought how many crimes I'd committed and became very religious. I would

have been capable of cutting my hair so that they should make me a wig. (I

was then 9 or 10).

There were five years between me and my brother. He was called Lorinc

Brull, and was also born in Kolozsvar. My brother played the violin, and I

really liked it. I studied it (the violin) at seven or eight with a private

teacher. She was Jewish and called Matild Laszlo. She was the only one in

Torda, so a small town violin teacher. She held lessons for pleasure. She

was rich, lived in several places. She had a house on the main square, I

went there for lessons. She had a lovely apartment. They also had a block.

They weren't religious. Her husband was a banker, called something Laszlo.

Her daughter was a violinist. I lived in that part (of town) where the

factories were - in the suburbs - and went into the centre for lessons

(which was quite a way). I went on foot, and always took my violin with me.

When I went for lessons I felt that it wasn't enough just to sit there. She

did not teach Jewish songs, just classical pieces, I even played in a

cinema with an accompanist before an audience. (Not before the film, just

in the building). The cinema had no name, it's a theatre today. This was

1940, I must have been 10.

My childhood friends were mostly Jewish - before the war - until I

went to high school. I could not have gone between 1940 and 45, during the

Hungarian period, (when the Hungarians annexed Transylvania) but I had

private lessons and took exams in the Jewish high schools in Temesvar

(Timisoara) and Bucharest. It was just that there was a Jewish High School

and they allowed us to take exams. Because here (in Torda) it wasn't

possible because of the racist laws. I could hardly wait to take exams, so

as not to lose the years. The school years were alright. There were books

at home I recall, it must have been possible to get them in the shops. I

was a private pupil, there was always someone to help me. One of them I

recall was called Zozo. She was a Jewish apothecary, older than me. She

taught me everything, mathematics for example. The rabbi's daughter - I

don't know her name - taught Hebrew, she knew it well. She must have leaned

from her father. She was a bit older and very cultured. She taught every

week once or twice, she had a text book. She did not teach prayers, we went

for the language, as we had to take an exam in Hebrew. And in drawing,

history, all the things which the others studied. A special exam was set

for private pupils. During the exams all the high school students (Jewish)

came in, and they all wanted to help so that I would be able to write down

what they (the teachers) asked. The school was strict, we didn't know as

much as they required for the exam. The teachers were fairly relaxed,

because we passed, that was the main thing. I sat the first and second

(high school exams) in Bucharest, the third and forth in Temesvar, I don't

know why. There was one other girl from Torda, Jutka Adonyi. My brother

took me to the exam, she (Jutka) went separately, because she had an aunt

in Temesvar. I was the only one in Bucharest. My brother always accompanied

me. We went by slow train, it was very long, it took 13 hours to Temesvar.

And the route was long to Bucharest too. There were steam engines and went

very slowly.

It was different for us at the end of the 1930s (than for Northern

Transylvania which was annexed to Hungary), because they let my father work

as they needed him. He was very diligent and lived for the factory. He was

very severe with the workers and always swore at them to work harder but

was one of them too. He was very just and honest. He always fought for

workers' interests. He did not ask for higher wages for himself but for the

workers. He was very modest, to the extent that the owner had to beg to

raise his pay. He always said - he did not speak Romanian well, had never

learned it - that "deti la muncitori, nu mie" (give to the workers not to

me). He did not want to be different from them, he did not want to be paid

differently. They always addressed him as "domnul conducator" (manager

Sir). The owner did not know what to do with him, to make him accept

something, then he bought (him) a house which was taken away from him (at

the state takeover), although they had no right to.

"Societatea Anonima" (this was the cover name for the factory) Iliescu, the

factory owner had to take on a female engineer from Iasi (in Moldavian

Romania) - (she was called) Elena Holban - as he could not keep my father,

(a Jew) as the chief. The woman did not understand porcelain manufacture,

she was a chemist, but on paper she replaced my father, who worked on. She

lived with us (she got a room). There were no other Jewish workers in the

factory (apart from my father). My brother even worked there for a while,

when there were anti-semitic things, so that he wouldn't be taken (to

forced labor), because then they took the Jews to Transnistria. He went to

work in Torda (posing as forced labor). In a word we did not feel (the

restrictions that preceded World War II). (Editor's note: as Torda was

under Romanian control the Jews were not deported).

On August 23rd 1945 Romania went across (to the Allies). This meant that

immediately afterwards the German troops sent reinforcements, they advanced

with Hungarian forces and occupied Torda. They took over the factory, over

everything that belonged to Romania and went forward. In the meantime the

Russians and the Allied Romanians advanced. So Torda became a frontline.

At the end of the war the Hungarians entered, and the Germans and we went

into the factory cellars (we hid there). My mother came up from the cellar,

up the steps for something and saw them taking our vase and carpets. They

took everything out of the house (and we saw it all) as we lived right next

door. Locals and soldiers took things away. And they took my violin, I

remember that. The German and Hungarian soldiers even slaughtered a pig in

the middle of the room. And they found prayer books (in the house) and came

into the cellar and said that if there were Jews, to hand them over

immediately. We were terrified someone would betray us. The others were all

Hungarians and Romanians, only we were Jews. People had run there from the

neighboring houses. It was war, there were no workers, no one worked (in

the factory then). So the Germans cooked there, baking bread in the

(factory) kilns. One of the Hungarians said that we should go with them if

we want to escape - because the Russians were coming - and they will take

us to Debrecen. So no one knew we were Jews. If they had they would have

killed us there and then.

Most of the inhabitants left (Torda). War was a time of fleeing, from

shooting. We did not go then. We only went when the Russians came in. Until

then we were (in the cellar). The big battle was just next to Torda,

Russians against Germans. Then some (of the inhabitants) fled to the

surrounding villages. They tried to flee to the villages of the Ore

Mountains and went on foot. In the first days, when there was shooting,

they obviously went into the cellars, and a few days after, when the front

was approaching they fled to the villages around Torda.

When the Russians came in they said there'll be a great attack. We were

hiding behind a door, they didn't know there were women there, or who, or

how many. And then we all processed out and set off on foot and we went

pretty far. My father did not want to come, he wanted to save the factory,

not let something happen to it. He stayed with Iliescu, they defended the

factory, they were afraid the Russians would get hold of it. He let us go

on alone. I went many kilometers with my mother. We fled to a village close

to Torda: Sinfalva, Cornesti in Romanian. My brother was elsewhere. He was

for a while an utecist (Uniunea Tinerilor Comunisti, the Communist Youth

League). He was a sympathizer of this illegal league and as such undertook

various tasks; but he wasn't a member. He fled to the mountains as there

were Russian partisans there. We found him with great difficulty, as he

came over there (to where we had fled). We had to take him up into the

loft, as they were looking for such "transfugo" (escapees), those who did

not go to fight. Then my father came for us in the village. When Torda was

liberated we returned. The apartment was robbed. A type of bomb (a

cannonball had smashed into the house) through the window, there was a

piano in one room and it had smashed into it. The rest of the apartment had

(just about) survived. When the war ended in 1945, I made up the time and

was able to complete my fourth year of school. Then I could go to high

school.

Lorinc (who often went to Temesvar for his exams) had a Jewish girlfriend

in Temesvar whom he courted. She was called Edit Kohn, she's now in Israel,

she got married to a doctor. (in 1945) it was not permitted to go into the

street after 6 pm, as there was firing between the German and Russian

soldiers that were still there. But (even so) Lorinc ran out for a minute,

as she (the girl) lived next door, and was shot down. Then people came to

tell us to go quickly as one from here (he had left from here) was lying on

the ground. (The whole family was very upset).

Luckily the factory was not badly damaged, and continued (its production).

Immediately after the war, when things were sorted out and (Transylvania

was under) Romanian authority, (my father) remained in a leading position.

He did a lot of (porcelain) exhibitions. And remained a "conducator

technic" up until the state-takeover. Then (in 1948) "they nationalized"

the factory and got rid of Iliescu. My father stayed. He didn't really like

it (the altered work situation) as they appointed managers who had no idea

about porcelain manufacture and (yet) began to give orders. After that I

went to Kolozsvar (to the music conservatory), and (my father also) wanted

to go there. But then they didn't really let one go from one town to the

next. (even so) he managed it with great difficulty, and came back to the

Kolozsvar factory, but not as a "conducator" (manager) but in a lesser

position. He was given the position of quality controller, and retired from

there. They wrote a lot about him (in the papers).

Despite the fact that he had come to Kolozsvar, his birthday was celebrated

every 5 years by both the Kolozsvar and Torda (porcelain factory work

communities). They liked him so much that they organized a joint dinner for

his birthday. This was rare (for a leading person), in general a person is

forgotten after 1-2 years. But they organized a party for him until he was

85 - that was the last one (as he was a great expert).

We met each other (Laszlo Nussbaum and I) at nursery and primary school, as

little boy and girl. But we were not in the same group (didn't play

together). At primary school we always had the same raincoat, I always

think of that. It was polka dotted and I was embarrassed to go into class,

that we had the same coat. When the war ended we went back to Torda (Laszlo

was later Silvia's husband, as a 16 year-old child he had been freed from

Buchenwald concentration camp. Nobody survived of his family in Kolozsvar

so he went to Torda, where one of his aunts and an uncle lived). I must

have been about in the 6th grade of high school and he entered the school,

and we got to know each other again. And he spoke Romanain well. Then he

always came to our house. (He listened all day while Silvia practised the

violin). My mother really liked him, as he substituted for my brother, (she

looked on him as a son). I did not know either his grandfather or

grandmother, only his aunt and uncle, as his aunt (Zita Weinberger,

Laszlo's mother's younger sister) was a piano teacher. Well she was a

lawyer but she taught piano. I played the violin and she accompanied. I did

not perform with her, she accompanied me at home. Sometimes I went to her

and we just played. Then both of us went to Kolozsvar to study, he went to

university and I to the Conservatory.

Laszlo Nussbaum, Silvia's husband tells that around 1949 there was great

hunger: there was no bread, nothing. Hunger was so great, especially in

Moldavia that many children were brought to Transylvania and put up for

adoption. After the war it was difficult everywhere and it was also very

dry. There was a canteen in the school and in the old houses there were

also rooms. They were much smaller than today's. They were not new. In the

first year Silvia lived in the metropol building with a family who had

converted to Christianity, they were called Wolf)

I was a second year (in 1952) when we got married (Laszlo had finished

university and was an assistant). There was no rabbi at our wedding, the

mayor married us. We lived in an apartment on the first floor of the Art

Cinema building. It had four rooms and four families lived in four rooms.

With a common larder and kitchen. Where we were there was a Jewish family

(our family), a Hungarian one and two Romanian ones. (these families) came

in (from the countryside) to Kolozsvar, as they wanted to work here.

Silvia's husband tells that when Silvia's parents moved back to Kolozsvar

in 1953-54, that is at retirement age - then a workers home, blocks near

the Kolozsvar porcelain factory were being built - and they were given a

small two-roomed apartment. In the meantime they started to build the

workers' blocks, including this block (where we live now). Then various

factories were given apartments, the factory (leaders) decided not the town

council, to whom to give them (of the workers). The factory had a list (of

the likely candidates), so that the factory organized (apartments) for the

workers. At that time I went to one of the managers and we got it (the

apartment) like that. I offered the apartment (where Silvia's parents

lived) and ours. And then we moved in together (into the present, third

apartment), there were five of us. This was at the beginning of the 1960s.

We both worked, what could we do with a small child (our son). And for

years my mother-in-law looked after him. My parents-in-law lived on the

factory site until then). So at that time this was a great solution, added

to which my mother-in-law cooked. It was very difficult for my wife, she

was with the philharmonic, they went on tour, organized concerts, she had

no time to cook. My mother-in-law was a housewife and she created a normal

life. We lived together in the flat: they lived in one room, my son in

another and we were in the third.

The mother and daughter were very different types of people. Her mother was

rather reserved, spoke little. Even her own daughter knew little about her.

In that period, when her son died, she did not even go out of the house for

two-three years. A few years went by and she slowly got her own self back,

and (became) a cheerful, optimistic, never complaining person. She did

everything for five people, today that's not so easy. We had no cleaner or

housekeeper and no washing machine. So she did washing, ironing, cooking

and a lot of shopping too. It only got easier when her husband retired. We

did not contribute at all, it was all taken on by her. But she even sang as

she ironed, never complained how difficult washing was. One person did

everything for five people, including big spring cleans. To the extent that

the child was never a problem. We only had to announce that we were going

somewhere. "Will you look after the child?", we went off for two months

with my wife on tour, I went to the sea, but it was never a problem.

Sometimes we went off and she used the opportunity (that the house was

empty) to paint the apartment before we came back. They died slowly (the

old), (Izsak Brull in 1979, Zsofia in 1996), the boy grew up and went, and

we remained behind together.

In 1955 I graduated from the Music Conservatory. It was good (to work at

the Kolozsvar Philharmonic) because we went on tour. It was only difficult

in that before 1989 we were cold, cut the fingers off gloves and played in

those. It was so cold that when conductors came from abroad they did not

want to conduct. They said that they couldn't in such cold. One bought

about 15 radiators so we would not be cold, and when he went they were all

collected up because a decree was passed - during Ceausescu - that

radiators were forbidden. It was hard to heat the rehearsal rooms as it was

very large and they didn't heat it well. So we froze as they were mean with

the heating during rehearsals and performances. Ceausescu passed a law

about conserving electricity. Otherwise they were good years, we were

abroad a lot. But we didn't get a big enough daily rate so we always took

tins with us and ate those to save money and to buy something for those at

home. Once, I believe in Italy, the boys cooked something in the hotel and

blew the fuses. There was a big row and articles were written (in the

papers there) about how the Romanain musicians live, and have to bring tins

(with them on tour). We went to many places. We were in France several

times, and in the ex-socialist countries: Bulgaria, Hungary,

Czechoslovakia, Poland and Russia.

There were some Jewish colleagues but not many. Ervin Junger in the piano

department. They were watched to the extent that one of them - Janos

Reinfeld, who was very talented and a soloist - was told that he could not

appear on the poster because he had a Jewish name. He is now in Germany,

before 1989 (during a tour) he "stayed behind". A lot of my colleagues did

that when we went on tour. Most of the orchestra was Hungarian, they could

not discriminate (between the Hungarians and Romanians). The atmosphere was

very good (during Communism between the Philharmonic musicians). Sometimes

they didn't allow someone to go abroad but not because they were Jewish or

Hungarian but because a security person had to go and there had to be a

place for them. Then they always left someone behind. Once they left me

behind just when we were going to Germany. And I asked why, because in

general they didn't allow those who had relations abroad. I said: "I have

no relations, they are all under the ground, or died in the gas chambers,

so why aren't you letting me go to Germany exactly?" And (without any

prompting) they said: we cannot allow you. I was always a little moved when

we played Jewish composers. But we did not play Jewish tunes specifically.

Jewish identity means (for me) that I was born one. It was often unpleasant

during the war. I thought of all the problems it caused: I could not study,

continue playing the violin. After the war I was quite proud that all the

best violinists are Jewish. Then I started to realize that it is not

something to be ashamed of. As they said that Jews were lazy, but it's not

true, so they twisted things.

Our son (Andras, who was born in 1956) is not circumcised. At the time my

husband didn't allow it, because he was afraid of losing his job. Then

everyone was Communist, and he was in the Party. Then they threw him out

the university (from his job as assistant), as he was in Hungary in 1956,

and when he came home, they threw him out for being in Hungary. Yet it was

quite by chance that he was there during the revolution. But at that time

his friend was also of the opinion that if he had a son he wouldn't

circumcise him. But later we regretted it. He still feels he is Jewish but

he cannot pray. Our son had Romanian friends at school, he was with them.

We only celebrated the Jewish festivals later when he was 16-18 years old.

At Pesach for a while my father read from the book and then Laszlo. My son

also went to synagogue on high holidays but otherwise not. He was a year in

Israel (Andras with his family in 1984) and learned Ivrit and it had a big

affect on him.

Silvia's husband says: my son met a Saxon girl from here (Transylvanian

German). They talked of getting married. I would have liked it better if he

had married a Jew. Mixed marriages are a problem, especially Jewish-German

ones. These two nations, since the Holocaust, are really removed from each

other. The in-laws met and the (girl's) mother said that she would really

like it if my son was married by a priest, She asked if I had any

objections. I said "It does not depend on me. It is up to my son, they are

getting married. But if you're asking me, I am very against it. I do not

ask for a religious wedding but I do not want him to leave the Jewish

religion. Let everyone keep their ethnicity, if they love each other they

will remain anyway." At this she said "Well I have no objections, let it be

a Jewish ceremony. I am very religious and I would like it of they do it

before God." A Saxon woman was capable of saying let it be according to

Jewish laws. I wouldn't have been capable of saying let's have a Lutheran

one. In the end they didn't have either. Let them be human and love each

other.

As far as I know their child did not receive a religious upbringing (Sonja

was born in 1982 in Kolozsvar), they did not christen her, but her mother

(Gerlinde, my son's wife) did make a Christmas tree. They do not observe

Hannukah and other Jewish holidays as my son is not religious. I said to my

daughter-in-law; "I wouldn't like my son to stay in Romania, as there is no

future for him here." And so it was, I didn't know whether I would see him

again but I was willing to let him go. I said there is one possibility (for

this) Israel.

They went to Israel with the child (in 1984) - on my advice -, and they

were put into language courses and special terminology courses. My son's

wife Gerlinde, a really German name. As the mother is not Jewish, neither

is the child. My granddaughter is Jewish everywhere in the world except

Israel. In Israel they got jobs, my daughter-in-law worked near Haifa in

Kirjat Jearim. No one ever asked my daughter-in-law if she was Jewish or

not. Of course not, because they really respected her. But my son did not

like it so much because of his colleagues, not (because of) Israel. In the

3rd-4th month in Israel they got a paper from the German Embassy saying

that they can go to Germany to settle. They did not understand why. Then

they got the answer, his wife's entire family were in Germany and had

arranged it, in that she was of German origin. They got to know that she

(Gerlinde) had gone from Romania to Israel (the embassy there had told

them) and within 6 months they went from Israel to Germany. My son is a

specialist in internal diseases, his wife is a planning engineer with a

company, (they live very well). My son visits the Stuttgart Jewish

community (where they live) but he does not have any position there.

I retired in 1986. Since then I am a pensioner. Until 1996 we could do

nothing else (with my husband) but look after my mother as she had

sclerosis, (and apart from this) had problems with her legs, as she fell

down. Neither of us works now, We were in Israel for the first time in 1994

or 95. I do no take part in the religious community but am a member of it.

My husband sometimes gave lectures about deportation within the community.

Now we only go to synagogue on high holidays. When there is a holiday -

Pesach, Purim - we eat at the community canteen as they organize joint

meals there. We go to be with other Jews and not because of the kosher

food. We eat paska then. We also celebrated Yom Kippur this year: we went

to synagogue, heard them (the prayers), but as they pray in Hebrew we did

not understand much.

Perhaps life is easier now, economically better. My husband gets some help

from Germany as he was deported. My son comes every quarter, he always

comes (from Germany) for my birthday. Most days I cook at home and

sometimes read.

Interviewer: Ildiko Molnar