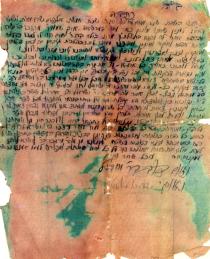

This is the ketubbah that my husband and I received on our wedding in the ghetto in Bershad in 1942.

[Beila met her future husband in the ghetto.] In july 1941 we were taken to the ghetto of Bershad: few streets were fenced with barbed wire. We stayed in our house. Life behind bars was terrible. In few weeks Romanian troops took command in the ghetto: our ghetto became a part of Transnistria. Once Eva who lived in our house came home with an acquaintance of hers, a young man from Yedintsy town [today Moldova] where the girl also came from. His name was Motia Gabis.

I didn't like Motia at first sight. He was wearing torn trousers and a ragged jacket. My mother and I were undoing old carpets for yarn and knitting woolen socks for sale. Motia started helping me. My mother liked Motia at once. She wanted to take Motia to live with us, but was afraid of rumors: he was a young man and I was a young woman… Then Eva said 'Why doesn't Beila marry Motia?' I didn't quite accept this idea. Motia visited us every evening. Once he said that if I married him I would never regret it, that he would care about me and we would have a good life. I agreed: not because I loved him, but because I felt sorry for him. He was very happy and kept telling everybody about the forthcoming wedding. There was a rabbi in the group of Moldavian Jews. He conducted the ceremony of engagement in accordance with Jewish traditions. He even issued a paper that I lost, regretfully, but I've kept ketubbah, a wedding contract, written on a page from a school notebook. We also had a chuppah made from old blankets. Our best friends held sticks with a chuppah spread on them. There was not one tallit in the ghetto: fascists took all tallits and tefillins away from older Jews. However, the rabbi wedded us and my mother gave her blessing. Shortly before the wedding Motia's former Ukrainian schoolmate Kolia Kolkey recognized Motia. He was recruited to the Romanian army and was a guard in the ghetto. He hugged Motia. He helped us a lot. He tried not to send us to work when he was on duty. Our wedding was when he was on duty, too. He brought some food and two live chickens to the wedding. Of course, it was a different wedding. We didn't have any guests since we were not allowed to gather in groups or walk in the streets after curfew. This happened in late 1942.

I often look at photographs in the family album. In one of them a rabbi hands beautiful dressed up Lena, my beloved granddaughter a ketubbah and I recall my bitter wedding in the ghetto and my ketubbah. Only because I kept this document I could prove that I was an inmate of a ghetto during the war. Now I receive a solid German pension. I wouldn't manage with the pension our state pays.