This is me at the age of eighteen, right after deportation. The photo was taken in Marosvasarhely, in the centre; there was a photographer called Horvath in the courtyard which is at the corner of the Bartok Bela street, where the Lottery is now. I remember that in those times they took photos by hiding under some kind of sheet.

Only three of the twenty-five families living in our village had members who came home. Everything was taken away from our house. They took everything that was made of wood, even the stairs and the well. The neighbors didn't tell a word, and they didn't give back what we had left there. Nobody had lived in the house, they only carried off everything. We didn't find any photos or papers, anything. We left the valuable things, the bed-linen at a person from Saratel, but they didn't give them back. Only my father and I survived, and we had to start again. We began to run a farm again, I even whitewashed the house, I painted patterns on the wall. Although we had the farm, one could not make a living of it, so my father started crop trading again, and he was transporting wheat to Beszterce to the same mills. The millers weren't Jewish, I think, but I'm not sure.

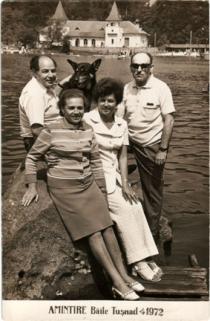

I spent one year at home, then I got married and moved to Marosvasarhely. My father stayed in Saratel.

After I came home, I spent my eighteenth birthday at home. Two men courted me at the same time. One of them was Nussbacher, whom I had met at the railway station in Kolozsvar, when we were coming home, the other was Joska Grunstein, my future husband. They were of the same age, and they were in the army together.

Nussbacher fell desperately in love with me. For my eighteenth birthday he brought me a manicure set and a photo of him; he was like a film star, yet I liked my husband better. I told him clearly that I loved him as my brother, but I wouldn't prefer him to be my husband. He had a brother in Kolozsvar who owned a chocolate factory; he also had a brother in Beszterce, so he stayed at them; this brother of him had a mill. The Bussbachers were very well-to-do Jewish people, they had a horse-drawn carriage. Later he changed his name into Alex. I didn't want to stay in the countryside. He told me: 'No problem, Beszterce is ten kilometers far. I'll buy you a cab, a car with driver, whenever you want, you can go to Beszterce. I'll take you to the cinema, to the theatre, wherever you may wish to go.' But I didn't want to. I told him: 'There are so many beautiful girls in Kolozsvar', but he answered he wanted none of them, just me. He was so reticent, in turn I was chatty. He told me I was like a chirping bird. However I didn't want to marry him.

I knew my husband before the war already; he was the cousin of my mother. He already had had a family. Once I visited Piri, my mother's sister in Marosvasarhely; she was the wife of my future brother-in-law. They lived in the Kossuth street. We came from the concentration camp, we didn't have any clothes. We had to have shoes, coats, everything made, so I went to buy materials with my aunt. My husband and I met at Piri's. My mother's little brother, Adolf was about to get married for the second time. All these people were relatives, we all got married with relatives in those times. She told Joska: 'Well, you should get married...', and she kept on praising me and telling how good housewife I was and how decent a girl I was. My husband lost his family in the concentration camp, and he was much grieved about it. But he started to think about us… For me, who I had lost my mother and siblings, he meant compensation. I was eighteen, and he was thirty-two years old. He was such a warm-hearted and kind man, there are just a few husbands like him. I became fond of him not as of a man, but because he was so kind-hearted. So finally I decided to marry Grunstein.

Nussbacher told me he would commit suicide if I didn't marry him. I didn't take him for serious. Many people said that I was a very pretty girl. I wasn't money-oriented, so I chose my husband, because if I had been selfish, I would have chosen the other. Nussbacher went to Kolozsvar, and committed suicide in his brother's bathroom. I was visiting my aunt, and my father came and told my aunt what had happened, and they didn't dare to tell me… Finally my aunt told me. I was struck dumb. They had to take me to a doctor.