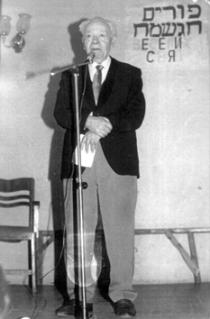

My father, Pinkhus Lubich, photographed at a wedding in Kiev in 1910.

My parents, Pinkhus and Malka Lubich, were born in a small town in the Zhytomir region in the 1880s. I don't remember where they came from.

My father was a tailor's apprentice in Kiev and eventually started his own business. My father had a traditional Jewish education. He studied in cheder and, after finishing school, began to study as a tailor in his hometown.

My parents grew up in religious families where Jewish traditions were observed. I don't know how they met. My parents got married in 1908. They had a traditional Jewish wedding with a chuppah at the synagogue. After the wedding my parents moved to Kiev.

I remember our house and our street well. We lived in a five-story apartment building, number 9, Andreevskiy Spusk Street. There was a signboard which read "Tailor Lubich" hanging on our building. It also said "Entrance from the backyard" in smaller letters. We lived in a big four-room apartment in the basement. We were a wealthy family, but there were no maids. There was one dark room without windows where we children slept. There was a big dining room, our parents’ bedroom, and another room with big mirrors and a cutting table where my father worked.

My father had two assistants to put fabrics that my father was cutting together. My father was a highly skilled master artisan: he received orders and cut fabrics. His assistants’ names were Mayorov, a Russian, and Vassilkoskiy, a Jew. I remember them so well since they were Bolsheviks and were involved in spreading revolutionary propaganda. My father sympathized with the revolutionary cause and helped them; I remember him hiding piles of the flyers brought by Mayorov and Vassilkovskiy in the storeroom. My mother wasn’t happy about his getting involved and used to warn him in a whisper that the whole family might suffer or be killed.

I remember the horseshoe clatter and the yelling and singing of the Petliura units that entered the town in 1917. There were other troops in town: the Reds and the Whites. The power switched from one side to the other throughout the course of a single day, but I only remember the reckless, drunk Petliura soldiers. A day before the Petliura units came to the city, my father’s employees Mayorov and Vassilkovskiy left town. They dropped by our apartment to say goodbye to my father and to tell us that the Bolsheviks would achieve victory and return. In the morning, the Petliura soldiers spotted the cannon in the square in front of our house and began to fire at our building. All the Jews were hiding in their apartments and nobody dared to go outside. Petliura soldiers found our building's janitor and forced him to show them the apartments occupied by Jews. They forced Jews to come out into the yard and shot them under the poplar tree. Many of my friends, along with the Pressman family and their numerous children, were killed. Our family was lucky; we were wealthy and paid a ransom - the soldiers took our carpets, china, cuts of expensive fabrics and bronze statues, and left us alone. At the end of 1918, Soviet power was established in Kiev. The Civil War was over and NEP began.

Our family observed Jewish traditions. We didn’t eat pork and followed kosher rules at home. I can’t remember any details about the Saturday celebrations, but I do remember that my father never worked on Saturdays. My mother lit candles and prayed over them on Friday and we had a festive dinner. The food on Saturday was made a day before and was left in the oven to stay warm. But my parents weren’t truly religious. They never prayed, but my father had a tallit, tefillin, and religious books in Hebrew - there were no other books at home. He had a seat at the synagogue at the bottom of Andreevskiy Spusk. He went there on Saturdays and on holidays with his tallit and tefillin on.