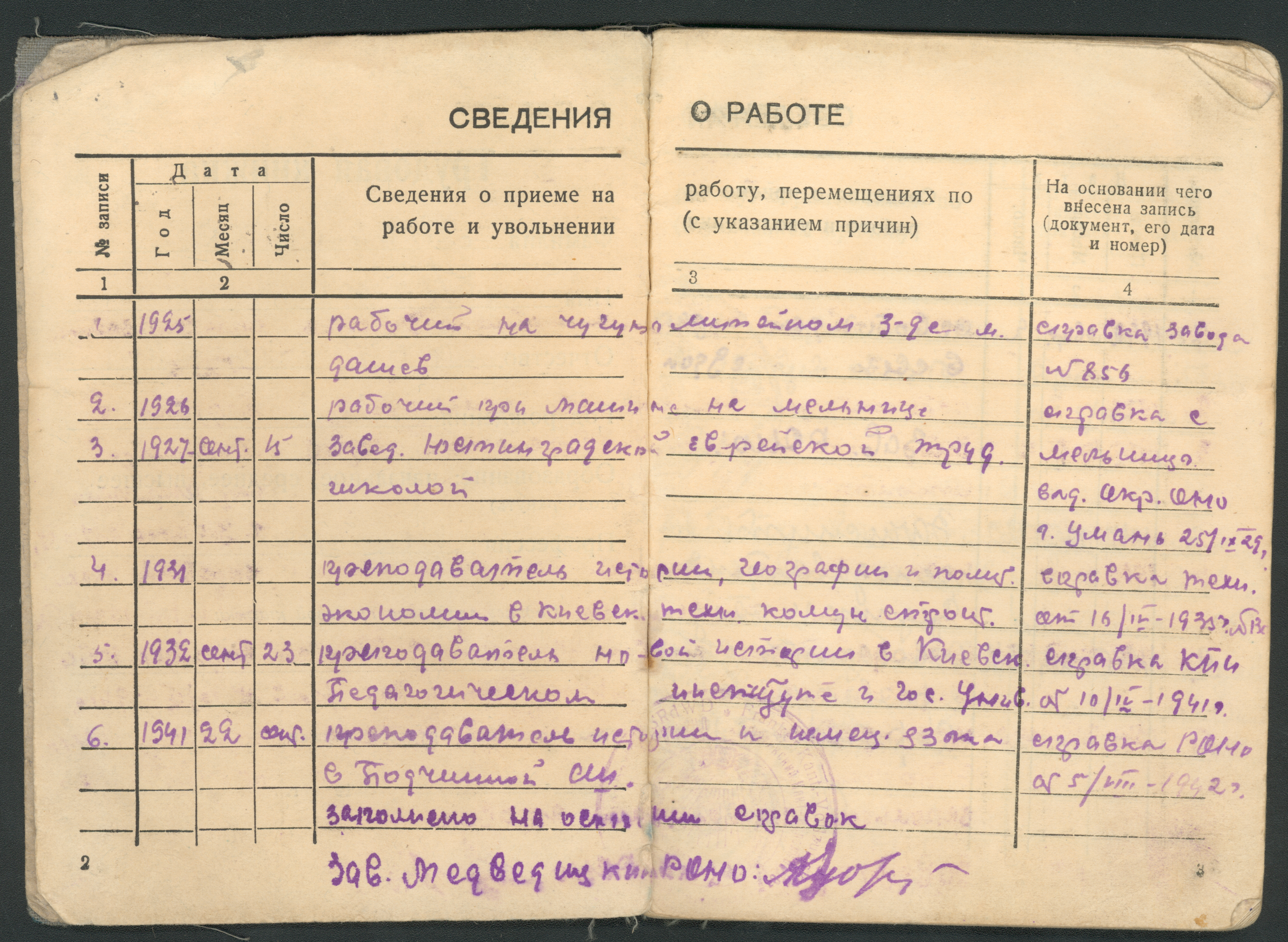

This labor card was issued to me in the Republic of German Povolzhye (the German settlement area of Volga region), where I worked for a short time as a teacher of German at a Russian school. In the republic of German Povolzhye labor cards and all formal documents were issued in two languages - Russian and German. One half of this labor card is completed in German, the other - in Russian. You see one of the pages in Russian. Thanks to this card I could restore my labor experience records and receive a pension in my old age.

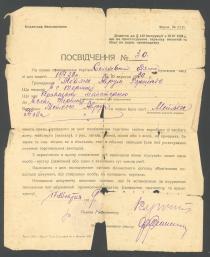

In 1941 I came back to my parents in Tyrlitsa. We were all together exiled to the area of German settlements in Volga region, the village of Gusenbakh. When we came we were allowed to settle in any house! The place was empty, houses open, furniture, home utensils – everything in its place, as if the owners had just come out and would soon be back. Even potatoes remained undug in the kitchen gardens. No people at all except for the exiled like us. All Germans were deported to Kazakhstan by then even without a chance to change clothes. And when the war began in summer 1941, they stopped releasing convicts at once. I returned to Kiev, but I didn’t stay there for long. I had article 39, ‘enemy of the people,’ in my passport, saying: ‘Without the right of residence in cities.’

After one year, in 1942, I was arrested again upon the accusation per the same article 39 – ‘enemy of the people’ – and exiled for lifetime to Kazakhstan. My parents remained in the German settlement area of Volga region. As a matter of fact, I had no serious incidents. Even in the prison camp, I enjoyed the warmest attitude from the brigade of porters, which consisted of the dispossessed men. I wouldn’t say that there existed any anti-Jewish, anti-Semitic laws that affected my family and me. The entire official system was such, all of it wasn’t very friendly. We tried to think about it as little as possible. Each of us did our own business, that’s all.

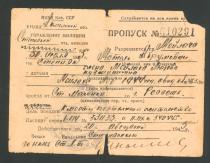

I found myself in the town of Akmolinsk in Kazakhstan for ‘lifetime settlement.’ I wanted to work. I found the regional department of people’s education and tried to find a job there. OBLONO gave me an assignment to Stepnyak. An inspector filled in an assignment for me and I bought a ticket and reached Stepnyak. I didn’t want to work in a school. I didn’t even think of school at all, but if you weren’t going on business you weren’t given railway tickets, and I wanted to leave Akmolinsk as soon as possible. I worried about the possibility of being arrested again. I was scared to start teaching at school! I got used to cutting timber in the woods and working as a loader in the camp. I was very nervous.

In Stepnyak I went to work as a day laborer, in the direct sense of the word, to one party boss. I dug the kitchen garden for him, and chopped firewood, and brought water, and cleaned the toilet. Everybody called me ‘Dekhterenko’s hand.’ He gave me a room, not heated in winter, and a large sack of hay, on which I slept, and an old sheepskin coat, with which I covered myself. I lived in his house for one year. After I got married, we were given a separate room. Other teachers knew that I was exiled, but treated me very warmly, with much sympathy. And I am grateful to them all until today.